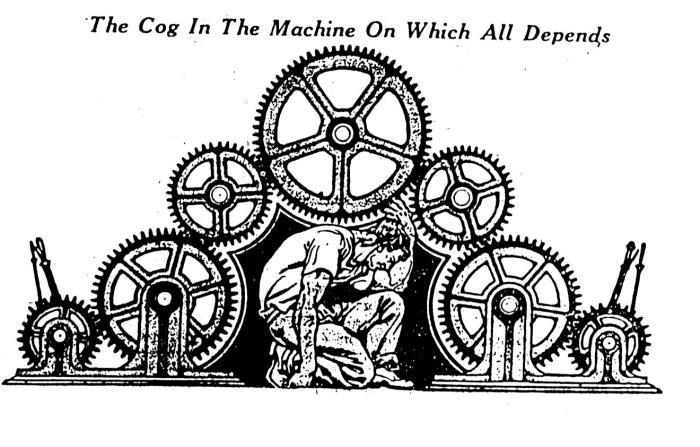

Because of a legendary incident in the Garden of Eden (for which Adam blamed Eve, who blamed the serpent), many Christians believe that work is a curse laid on sinful humanity: “Cursed is the ground for thy sake; in sorrow shall thou eat of it.… In the sweat of thy face shall thou eat bread.” But vast numbers of workers who care nothing for biblical stories have the same opinion. They judge by what they know and they judge that work is by nature evil: but all they know is what work is like under capitalism. They have not realised that the evil does not work itself but the conditions under which they carry it on when they leave the comparative democracy of their leisure hours for the dictatorship of the capitalist factory or workshop. Not the activity of producing useful articles but the drab surroundings, the discipline, the long hours, the bullying, the intense speed, and the knowledge that the work is carried on not for the good of the community but for the profit of the shareholders. These things need not be. Under socialism, they will not be. It is at the forefront of the Socialist purpose of real reconstruction that work shall take its proper place as a pleasurable activity worthy of free men and women, duly balanced against opportunities for enjoying leisure. The Socialist principle, “From each according to ability: to each according to needs,” does not envisage perpetuating work as a penance, work as the worker knows it under capitalism. The worker will not be a numbered unit in a stupid machine for turning out cheap and nasty articles of merchandise for the profit of the few.

Socialists know these elemental truths, but the social reformers, their judgement warped by concentration on the limited scope of improvement under capitalism, are in the main blind to the great possibilities of life and work under Socialism. Many years ago the S.P.G.B. rescued from undeserved oblivion William Morris’s “Art, Labour and Socialism,” in which the truth was proclaimed by a man who understood that subject in all its aspects. Morris had his limitations, but he was right in his insistence that capitalism, along with its economic exploitation of the working class, had committed the crime of compelling many workers to perform degrading tasks under conditions robbed of all pleasure and intelligence. He rejected the shallow view that all we can do, and want to do, is to take over the capitalist industry as a going concern and put it under new management. He saw that with the abolition of capitalism socialists will get rid of the profit-seeking that has corrupted the production of wealth. “That system,” he wrote, “is, after all, nothing but a continuous implacable war; the war once ended and commerce, as we now understand the word, comes to an end, and the mountains of wares which are either useless in themselves or only useful to slaves and slave-owners, are no longer made, and once again art will be used to determine what things are useful and what useless to be made; since nothing should be made which does not give pleasure to the maker and the user.” He was not, as some of his admirers have supposed, aiming at putting back the clock and dispensing with machinery. He knew this could not be done, but he also saw that machinery which could have been used to minimise that necessary labour, not pleasant in itself, had not been so used under capitalism. He echoed J. S. Mill’s doubt whether all the machinery of modern times has lightened the daily work of one labourer. Instead, capitalism has imposed on its machine slaves “plenty of unnecessary labour which is merely painful.”

Elsewhere, in his pamphlet, “A Factory as it might be,” Morris dealt one by one with many of the problems to be faced. One of his shrewd observations was:

“In a duly ordered society, in which people would work for a livelihood, and not for the profit of another, a factory might not only be pleasant as to its surroundings, and beautiful in its architecture, but even the rough and necessary work done in it might be so arranged as to be neither burdensome in itself nor of long duration for each worker; but, furthermore, the organisation of such a factory, that is to say, of a group of people working in harmonious co-operation towards a useful end, would of itself afford opportunities for increasing the pleasure of life.”

He knew these things would never be done under capitalism.

Now, half a century afterwards, when technical developments have made the problem still easier to solve, thousands of social reformers are busily engaged in post-war plans for reorganising our education, our work and our lives within the framework of capitalism and for the purpose of enabling that capitalist country in which they happen to live to be a more ferocious and formidable competitor in the continuous implacable war of international commerce. They are the enemies of Socialism and of the health and happiness of the human race.

Through ignorance, class interest, or the mistaken notion that compromise with capitalism is justified for the purpose of niggling ameliorations of the hardships of the workers they have rejected the prime and urgent necessity of destroying capitalism, root and branch. Within the limitations they have imposed upon themselves they cannot even conceive that work and the conditions of work could be fundamentally changed. It is for socialists to bring the working class to recognise the truth of which their leaders and “thinkers” are unaware.

From Editorial from the October 1942 issue of the Socialist Standard

Much of the World Socialist Movement’s critique of work under capitalism is shared by others such as Michael D. Yates in this extract demonstrates:

”…Anthropologists tell us that our ancestors didn’t have to exert an extraordinary amount of energy to provide life’s necessities; there was plenty of time for what today we might call leisure activities: singing, dancing, chanting, drawing on cave walls. People performed complex tasks, the learning of which helped mark the transition from child to adult, as a member of a cohesive community. The distribution of what was produced was remarkably equal by today’s standards, and skill at something like hunting did not guarantee a larger proportion of the resulting food. Of considerable importance, work did not much disturb the metabolism of the natural world. The gatherers and hunters acted as one with the earth.

By contrast, work in modern society is a torment, an affliction arising from the nature of the economic system, which could not be more antithetical to the way we labored for more than 95 percent of the 200, 000 years of Homo Sapiens’ existence. Our labor has become a commodity, something bought and sold in the marketplace, just like any other commodity, no different in principle than raw materials, equipment, and the buildings that house our workplace. And just as these non-human commodities are the property of those who own them, so too is our capacity to work. When we are working, we, in effect, belong to our employers…

…Is there a solution? Not within this system. No amount of union organizing or progressive legislation will alter the nature of work in it. Only a radical change in how work is done and who controls this can make labor once again an integral part of life, one through which we can fully develop our capacities as thinking, acting human beings. Cooperatives and communes, organized and controlled locally, are two avenues to pursue. Producing goods, especially food, and services for use not for profit. But whatever is done, it must be radically democratic, and what is produced must be socially useful, ecologically regenerative, and distributed as equitably as possible. This might sound utopian. But how is what we have been doing going for us?”

Taken from