From the September 1919 issue of the Socialist Standard

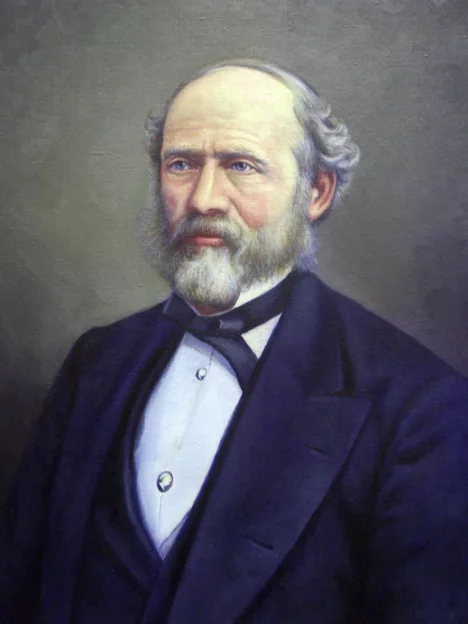

The year 1818, which witnessed the birth of Karl Marx, also saw the birth, on Nov. 21st, of Lewis Henry Morgan, a man whose investigations into the nature of primitive human society were as epoch-making as were those of Marx into the structure of modern capitalism. Born at Aurora, Cayuga County, in the State of New York, and of “middle-class” parents, Morgan, after the customary school education, graduated, at the age of 22, at Union College, N.Y. Afterwards he underwent a four years course in law, and in 1844 was admitted to the Bar. In partnership with his old schoolmate, afterwards Judge G. F. Danforth, Morgan practised successfully as a lawyer in Rochester, where he made his home.

Studies of the Indians.

While at college young Morgan had become deeply interested in the Red Indians of the Iroquois tribes, the remnants of a once powerful and widespread people, in the State of New York. After his graduation he joined with a number of young enthusiasts in Aurora who, like himself, were fond of Indian lore, forming a club or society which was called the Grand Order of the Iroquois. The “Order,” which was of the nature of a secret society, also appears to have been known as the “Gordian Knot.”

The idea of its founders was to extend the organisation over the tribal territory which the Iroquois in times past had occupied. Branches were to be established wherever a settlement of the Iroquois was known to have existed, and “council-fires” held at night for the discussion of matters relating to the Indians.

In order to study more intimately their life and institutions Morgan actually went into an Iroquois settlement, and there lived as one of themselves for periods which eventually totalled several years. So well did he gain the confidence and affection of the Indians that in 1847 he was permitted to formally enter, by adoption, into the Hawk gens of the Seneca tribe. They recognised in him a fraternal link between the white men and the red, and gave him the name Ta-ya-da-wah-kugh, meaning “one lying across.”

The first results of his investigations Morgan embodied in a series of papers which were read to the “Grand Order,” and also to the New York Historical Society, of which he was a member. Subsequently they were published as “Letters on the Iroquois;” under the pen-name of “Skenandoah” in the “American Review” during 1847, and later appeared in other journals.

Among Morgan’s closest associates was a pure-blooded Seneca Indian called Ha-sa-no-an-da, who had adopted the English name of Ely S. Parker. He was well educated and a civil engineer by profession. Hasanoanda possessed an exceedingly full knowledge of Iroquois customs and institutions and was himself a Sachem or peace-chief of the Senecas, his name signifying “Keeper of the Western door of the Long House” (see below).

With Parker’s assistance Morgan was able to carry his researches into the past history of the Iroquois and to complete his first great work on primitive society, “The League of the Iroquois,” which he published in 1851. This book which Morgan, out of recognition for his services, inscribed to Ely S. Parker, was written, as the author says in the preface, “to encourage a kinder feeling towards the Indian founded upon a truer knowledge of his civil and domestic institutions, and of his capabilities for future elevation,” surely, in view of the brutal treatment meted out to the Red-man by the Paleface who had robbed him, a noble ideal.

The first scientific account of an Indian people ever written, this book contains a detailed description based on personal observation of the society, religion, ceremonial, games, art, craftsmanship, and language of the Iroquois. A new edition appeared in 1904.

The league of tribes was the highest type of social organisation achieved by the American Indians. That of the Iroquois was formed in the fifteenth century and consisted of five, and later of six, tribes, the Mohawks, Cayugas, Senecas, Onondagas, and the Tucaroras. The term “Iroquois” is believed to be of French origin. They called themselves Ho-de-no-sau-nee, the “People of the Long House,” the latter allusion being to the Indian communal house which was chosen as tie symbol of the League. At the time when Morgan wrote, however, the League was but a shadow of its former self, having lost, with the coming of the Whites, the position which had made it a social and military power of no mean importance.

In 1855 Morgan was concerned in an engineering scheme to build a railway through the wilderness of North Michigan, and in conjunction therewith performed some practical exploration which was much needed in this, at that time, little known region. When thus engaged he made some original investigations into the social habits and constructive ability of the beaver, an animal which was exceedingly abundant in this area. His results were embodied in “The American Beaver and His Works,” published in 1867. One of the most perfect of zoological monographs, this work drew praise from Darwin, although he considered that Morgan had underestimated the power of instinct and thus rated too highly the reasoning powers of the beaver.

In 1856 Morgan made the acquaintance of Prof. Henry, of the Smithsonian Institute, and of Agissiz, the famous American naturalist, both of whom encouraged him to continue his unique Indian studies.

Studies in Kinship and Sex Relations.

While on a visit in 1858 to Marquette on Lake Superior, one of the terminii of the proposed railway, Morgan visited a camp of the Ojibwa tribe and there discovered the same peculiar system of recognising family relationships which he had found among the Iroquois. According to this system a man referred to the children of his brothers as his own “sons” and “daughters,” and all these “cousins” as they would be termed by us, called one another “brother” or “sister.” Likewise with the children of several sisters.

The discovery that this system existed among the Ojibwa appears to have been somewhat of a revelation to Morgan, and he now pursued his ethnological researches with redoubled vigour, visiting in the next three or four years different tribes in the extreme West and as far North as Canada. He found, as he had begun to expect, that the same system of kinship was characteristic of practically all the tribes in North America.

After this Morgan, with the assistance of the United States Government, carried his investigations into other lands. Carefully prepared lists of questions were forwarded to officials, explorers, and missionaries in different parts of the world. Most of these lists were returned with the desired information, and by this means Morgan was successful in acquiring a vast amount of data bearing on the sex relations and kinship of numerous peoples the world over.

It was a stupendous task to sort out and classify this mass of evidence, but Morgan performed it with great ability and remarkable results. These were set forth in a preliminary essay published in the “Proceedings of the American Academy of Sciences” in 1868.

The complete and tabulated results of these investigations appeared in the “Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family,” published in 1871 as Vol. XVII. of the “Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge” by the “Institute.” This work, containing as it does the kinship systems of one hundred and thirty-nine distinct peoples comprising about four-fifths of the human race, is one of the landmarks of ethnology and denoted the entry of exact scientific method into the study of primitive society.

Frederick Engels in his “Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State,” thus summarises Morgan’s conclusions :

- The kinship system of the American Indians is also in vogue in Asia, and in a somewhat modified form among numerous tribes of Africa and Australia.

- This system finds a complete explanation in a certain form of communal marriage now in process of decline in Hawaii and some Australian islands.

- By the side of this marital form, there is in practice on the same islands a system of kinship only explicable by a still more primeval and now extinct form of communal marriage.

Morgan was led by his researches to the belief that unrestricted sexual intercourse had been the habit of primeval mankind. Progressive restriction upon intercourse between near blood relatives then resulted in two successive forms of group or communal marriage in which a group of men were common husbands to a similar group of women. This custom, by rendering actual fatherhood uncertain, necessarily resulted in the tracing of decent through females only, a fact which had already been inferred by Bachofen in his “Mother Right” (1861) from a study of classical mythology.

Further restriction led to a loose “pairing family”—the intercourse and co-habitation of one man with one woman—and then, as Morgan subsequently showed, the rise of private property formed the basis of the historical from of monogamy, with its permanent union and male inheritance.

In treating anomalous kinship-systems as the vestiges of extinct marital and family institutions, and in coming forth as the ethnological champion of the theory of original promiscuity and of group marriage, Morgan encountered the opposition of the “established school” of anthropologists led McLennan. Just as Owen, Virchow, and other reactionary scientists endeavoured to save the “respectability” of man kind by denying, in opposition to the Darwinians, our animal ancestry, so Westmarck, Andrew Lang and others fitted bourgeois morality upon the primitive savage by declaring, against Morgan and even Lubbock, that human sex-intercourse had never been promiscuous and that monogamy was its “natural” and original form.

Morgan’s views on this matter have, in the main, been amply vindicated by the more recent painstaking researches of Spencer and Gillen into the communal marriage systems of the Australian aborigines.

The Roots of Cultural Progress.

After the publication of his ”Systems of Consanguinity” Morgan pursued the investigation of several series of facts which had attracted his attention whilst accumulating the materials for that important work.

The only literary fruits of his work during the following five or six years were a number of essays on the ancient culture of Central America—a line of enquiry which greatly interested him. Between 1869 and 1876 there appeared in the form of magazine articles “The Seven Cities of Chibola,” “Montezuma’s Dinner,” and “The Houses of the Mound Builders.”

Morgan was something of a classical scholar, and it gradually became apparent to him that there was a more intimate affinity between the social institutions of early Greece and Rome and those of existing barbarian peoples than was usually supposed.

He also became aware of the great changes wrought in social and cultural institutions by progressive improvements in man’s means of living.

Thus by a variety of channels he arrived at the conception of the essential unity in the course and method of evolution throughout the entire human race. The great antiquity and animal origin of mankind had already been established, but little knowledge had as yet been gained as to the social conditions of existence among primitive men.

Morgan was among the first to scientifically penetrate into the social status of man in the stages proceeding the patriarchal system which, in conformity with Hebrew tradition, most earlier writers, even the learned Sir Henry Maine (“Ancient Law,” Chap. 5), had considered to be the dawn of society.

In 1877 Morgan gave to the world the result of forty years study in his chief literary work, “Ancient Society, or Researches in the Lines of Human Progress from Savagery through Barbarism to Civilisation.” The book is divided into four parts. In the first Morgan shows that the basis of all human progress lies in the discovery or invention of artificial aids to existence in the form of implements and technical processes, and that these processes lead to new methods of living, generating new needs and producing a gradual increase in man’s knowledge of and control over natural forces.

The author divides the evolution of mankind into seven stages, each marked off by outstanding discoveries. Thus the lowest or first stage in the period of savagery commences with man, hardly differentiated from the rest of the anthropoid stock, existing as a tropical tree-dweller and consuming raw roots, fruits, and small animals. During this period the first simple form of language was developed and rude tools of stone, shell, bone, and similar materials began to be used.

Then came the making of fires, which made cooking possible and raised man to the second stage of Savagery. Fishing was now adopted and by encouraging migrations along river banks and coasts assisted in the dispersal of the race over the continents. The invention of the bow and arrow ushers in the third stage, in which the savage was equipped for the hunting of large game.

With the art of making pottery the period of Barbarism begins. In its first stage crude picture-writing and probably weaving were evolved. Primitive agriculture commenced to wards the close of this period. Then with the domestication of cattle, sheep, and other hoofed animals in the Eastern Hemisphere and the improvement of agriculture in Central and South America, the middle stage of Barbarism would be reached. This period, in its use of the softer metals, corresponds with the Bronze Age of the archaeologists.

The upper status of Barbarism was reached only in the Eastern Hemisphere when iron smelting was achieved. This great discovery, which placed in man’s hands the means of procuring tools of great hardness and durability, gave an unprecedented impetus to agriculture and other forms of production. The invention of alphabetic writing closed the epoch of Barbarism and ushered in the era of written history—of Civilisation.

Morgan’s orderly classification of the cultural history of mankind was a marked advance upon all previous attempts. It is still, over forty years after its formulation, recognised as the most adequate and useful of the many schemes which have been evolved (see article “Civilisation,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th edition).

To Socialists Morgan’s classification is especially of interest inasmuch as it is based upon the principle that “the great epochs of human progress have been identified, more or less directly, with the enlargement of the sources of subsistence” (“Ancient Society,” p 19), a thesis fundamentally identical with the Materialist Conception of History of Marx and Engels.

The Discovery of the Gens.

The second part of “Ancient Society” contains the fruits of those researches of Morgan’s which it is generally recognised constitute his greatest contribution to sociology. Prior to its appearance there existed little or no exact knowledge of the tribal organisations of primitive peoples.

In his “League of the Iroquois” and even later works, Morgan himself had adhered to the commonly accepted view that the Mohawks, Senecas, etc., were each nations in many ways equivalent to modern national communities. The smaller groups within these “nations,” each of which was called after a certain animal which was its totem, Morgan had designated “tribes.” Subsequent investigation, however, convinced him that the larger groups, the Senecas, etc., were the true tribes, and that they were different from the nation which only came into existence after the coalescence of several such tribes, and fundamentally so from the modern territorial nation, in which kinship as a social tie is eliminated.

But the most important fact was that the basic and unitary organisation of the Indians was the smaller group, that which he had earlier called the “tribe.” This “clan” or “totem group” he soon recognised, as his researches expanded, to be an all but universal institution among savage and barbarian peoples. Everywhere it consisted of a group of blood relatives descended, or claiming descent, from a common ancestor. Its members were strictly bound not to intermarry, but to mate outside the group ; they elected and deposed their own chiefs, and met together in common council.

Then Morgan made a remarkable discovery. Even the most learned and acute historians up to his time had been greatly puzzled over an institution which existed among the ancient Greeks and was known to the classical Latin writers by the name of “Gens.” Being unable to understand its structure or function, Grote and other historians erroneously considered the gens to be an extension and outgrowth, of the monogamous family. Morgan, however, showed convincingly in his “Ancient Society” that the Greek and Roman gens is identical in all essentials with the Indian “totem group,” the only important difference between them being that among the Indians, except where European influence had crept in, the common ancestor of the group was a woman, female descent prevailed and children always remained in the same totem group as their mother, whereas among the early Greeks and Romans the recognised ancestor was a male, paternal descent was the rule, and children belonged to the gens of their father.

Morgan considered the former an archaic or primitive, and the latter the derived and modified, form of the same organisation, which he decided out of consistency to henceforth refer to by its Latin name of “gens.” He believed that the change from the maternal to the paternal gens was an outcome of the growth of private property, possession of which instilled into the fathers a desire that this wealth should be enjoyed, after the death of themselves, by their own children.

Under the law of the gens the property of a member had to remain within the group, and as the maternal system placed a man’s children in their mother’s gens, never in his own, they were disinherited as regards their father’s property. By introducing male descent and thus keeping children in their father’s gens they were enabled to inherit his property. Morgan clinched his argument by showing this change to have actually taken place in recent years with the growth of private property among several Indian tribes as a result of foreign influences.

Having thus placed ancient history upon a sound basis Morgan endeavours to show the stages by which, in Greece and in Rome, the social organisation of the gens and the tribe passed away and was supplanted by a form of society based upon possession of property and territorial residence. In a series of brilliant chapters he shows how increasing population, intermixture of tribes, growing division of social functions, and above all, the increase in private property and its concentration into the hands of a few, all results of the “enlargement of the sources of subsistence,” gradually undermined the institutions founded on kinship and prepared the way for and made necessary the rise of the political State.

Morgan’s analysis still holds good, but it may be usefully supplemented by Engels’ “Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State,” which shows that class-oppression is the function of the State-power. Morgan did not deal with the feudal form of political society which developed from gentile society in a somewhat different fashion, but Engels outlined its beginning among the Germans and it has been adequately if briefly treated in a generalised manner by Edward Jenks in his “Short History of Politics.”

One of the most instructive and important chapters in “Ancient Society” treats of the native culture of Mexico prior to the Spanish Conquest. Investigation had convinced Morgan that the records of the Spaniards, together with the historic works which, like Prescott’s, were built upon them, were very unreliable wherever they dealt with the social institutions of either the Aztecs or the Incas of Peru. The Spaniards, accustomed only to the social relations of a feudal monarchy, completely misunderstood what little they did observe of Mexican and Peruvian society. They interpreted the league of tribes as an empire and the war-chief of the Aztec federation as an Emperor.

Morgan did valuable pioneer work in unravelling the mystery of “Aztec civilisation,” and had already criticised the prevailing misconceptions in some of the articles we have referred to. Moreover, in this field he had the assistance of his friend, Adolph H. Bandelier (1840-1914) a Swiss who had gone to America, and the leading authority at that time on the archeology of Mexico, Arizona, and New Mexico

In “Ancient Society” Morgan’s conclusions were fully stated and the evidence massed which showed that the Aztecs were, at the time of their discovery by Europeans, in the Middle Status of Barbarism, intermediate between the Iroquois and the Greeks of the Homeric period, and that they lived in village communities based upon the gens.

By revealing the inner structure of tribal society Morgan performed a signal service to sociology. Incidentally he showed and was one of the first to appreciate the fact, now generally recognised, that the barbarian is not a bloodthirsty monster of ferocity, and that his society, far from being a despotism ruled over by a brutal, tyrannical chieftain, is usually a well-organised, democratic body.

“All the members of an Iroquois gens were personally free, and they were bound to defend each other’s freedom; they were equal in privileges and in personal rights, the sachems and chiefs claiming no superiority ; and they were a brotherhood bound together by ties of kin. Liberty, equality, and fraternity, though never formulated, were cardinal principles of the gens.” (“Ancient Society“, p. 85.)

The Family and Property.

In the third part of “Ancient Society,” which describes the evolution of the family, Morgan not only re-stated his theory (which we have already outlined) in a revised, more complete, and widely generalised form, but he devoted a special section to a refutation of the criticisms of McLennan, the author of “Primitive Marriage.” He was now in a position to show that McLennan’s position was, in the light of the fresh discoveries, completely untenable, his theory of tribal Endogamy and Exogamy being due to the common confusion of the gens with the tribe.

Morgan’s theory of the family is generally accepted to-day in its main outlines. His most important error lay in considering the patriarchal family to be an exceptional form instead of, as has been since shown by the Russian student, Maxim Kovalevsky, and others, to be a widespread institution characteristic of the Middle and Upper stages of Barbarism, and as the intermediary almost everywhere manifest between the matriarchal family and monogamy.

In his concluding part Morgan outlines his view of the development of property. He shows how, feebly developed and largely communal during Savagery, it achieves more definite recognition and power during the pastoral stage in the period of Barbarism and reaches almost complete dominance in social life with the greatly increased productivity of the epoch of Civilisation.

He defines three successive systems of property inheritance, the first two of which correspond with the two stages of female and male descent in the gens among the members of which the property of a deceased member was divided ; the third system harmonising with the monogamous family in which the father’s property is inherited exclusively by his own family.

Morgan’s observations on the social significance of private property are very acute and approximate very closely to the Marxian position. He says:

“It is impossible to overestimate the influence of property in the civilisation of mankind. It was the power that brought the Aryan and Semitic nations out of barbarism into civilisation. The growth of the idea of property in the human mind commenced in feebleness and ended in becoming its master passion. Governments and laws are institute with primary reference to its creation, protection, and enjoyment. It introduced human slavery as an instrument in its production ; and after the experience of several thousand years, it caused the abolition of slavery upon the discovery that a freeman was a better property-making machine.” (Pp. 511-512.)

“The time will come, nevertheless, when human intelligence will rise to the mastery over property . . . The interests of society are paramount to individual interests, and the two must be brought into just and harmonious relations. A mere property career is not the final destiny of mankind, if progress is to be the law of the future as it has been of the past. The time which has passed away since civilisation began is but a fragment of the past duration of man’s existence ; and but a fragment of the ages yet to come. The dissolution of society bids fair to become the termination of a career of which property is the end and aim ; because such a career contains the elements of self-destruction.” (P. 561.)

Final Work.

With the publication of his principal literary work, the real culmination of his long enquiry into the evolution of human culture, Morgan did not by any means rest from his scientific labours. A true scientist, he continued to investigate and to generalise from the facts so observed, ever searching for fresh truths, ever seeking further to contribute to the totality of human knowledge.

In 1876 he visited the ancient and the modern pueblos, or native villages of Colorado and New Mexico. An early result was his essay on “Communal Living Among the Village Indians.”

He devoted his attentions especially to the architecture and domestic life of the Indians, and his final conclusions on this phase of their life were embodied in his last great book, “Houses and House-life of the American Aborigines,” which appeared in 1881. This work contains abundant information on the property relations of the Indians and shows in great detail the communistic habits and modes of thought which pervaded their life. Commenting upon the brotherhood and hospitality of the Redskins Morgan, says in a striking passage:

“If a man entered an Indian house in any of their villages, whether a villager or a stranger, it was the duty of the women therein to set food before him…This characteristic of barbarous society, wherein food was the principal concern of life, is a remarkable fact. The law of hospitality, as administered by the American aborigines, tended to the final equalisation of subsistence. Hunger and destitution could not exist at one end of an Indian village or in one section of an encampment while plenty prevailed elsewhere in the same village or encampment.”

We have now completed our survey of Morgan’s scientific and literary achievements. His important and original work earned for him the name of “the father of American Anthropology.” In 1873 he had received the degree of Doctor of Laws from Union College, and in 1880 he was President of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

At first sight it appears strange that although his vital discoveries were appropriated for their own use by the English anthropologists, to their great discredit they did their utmost to belittle Morgan, and as far as possible ignored, and were silent regarding, his meritorious achievements. No doubt this, in part, was due to the severe blow which Morgan had dealt to the prestige of the English School by causing the collapse of their pet theory—that of McLennan. But, worse still, Morgan had criticised the social power of property, and such criticism could not be tolerated by the intellectuals of the hothouse of industrial capitalism, the birth-place of Laisser-Faire “political economy.” *

Morgan’s home was a rendezvous for the leading American scholars and scientists of the day. In his own library Morgan would often gather with a number of young students for the systematic study of ethnology and also of the works of Herbert Spencer, whom he greatly admired.

Morgan took a practical interest in political activity and in 1861 was elected to the N.Y. Assembly, later, in 1868, becoming a Senator. He used all his influence in the endeavour to improve the conditions of life and the treatment meted out to his life-long friends, the Red-men—dying remnants of a splendid race, broken and bespoiled by the fateful finger that writes the story of economic evolution.

Morgan reached through his studies the very verge of the Socialist conception of society. Had his investigations carried him further into the epoch of civilisation he would probably have realised more completely than he did the vast importance of the struggle of classes arising from those property developments the early stages of which he himself so ably described.

But if his sphere was too narrow to permit of this, it was even less fitted to give Morgan an understanding of the present capitalistic stage of society. It required a man of equal intellect working, observing, analysing, generalising at the very hub-centre of the capitalist world market —London, and this role was played by Marx, in whom Capitalism as well as Socialism found its Morgan.

The works of Marx and Morgan are in a very real sense interrelated and complementary. Together they laid secure foundations for a genuine natural science of social life. This Marx clearly recognised and intended to show in a work upon the evolution of society based upon his own researches and those of Morgan. Unfortunately this, which might possibly have been Marx’s master work, was never accomplished—ill health and death intervened. But Marx’s great co-worker, Frederick Engels, seeing the urgent necessity of such a work, himself undertook the task and produced that classic of Marxian sociology, “The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State,” which first appeared in Germany in 1884.

This little book of Engels’ was the first real appreciation, outside of America, of the pioneer work done by Morgan. Passing through several editions and translated into numerous languages, it has been the means of spreading a knowledge of Morgan’s work amongst members of the working class the world over. To this day, in fact, “Ancient Society” is read and discussed wherever class conscious working-men gather together, while, on the other hand, the average bourgeois student is ignorant, often enough, of Morgan’s very name and position in science, let alone being conversant with his writings.

In the estimation of the proletarian student Lewis H. Morgan, by the originality and vast importance of his scientific achievements, occupies a place in that imperishable trinity of nineteenth century science —Marx, Darwin, Morgan.

R. W. Housley.

* Of late years there has been a change of attitude, and in addition to the praise of Edward Jenks, we have Dr. Haddon in his “History of Anthropology” referring to Morgan as the greatest sociologist of the nineteenth century.

Further Reading