The State and its abolition

From the Spring 1985 issue of the World Socialist

(Part 1)

Introduction

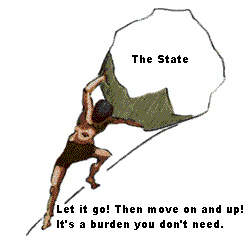

The establishment of world socialism will involve the abolition of the state, but this must be achieved by first gaining control of the entire powers and machinery of governments, including the armed forces. The practical question involved in this is that the socialist majority must be in a position to implement its object. It must be in a position to control events, which means being in a position to enact the common ownership of the means of production, and to ensure that society is completely transformed on this basis. At the centre of capitalist class power is their control of the forces of the state, therefore this must be taken out of their hands.

The operation of the entire capitalist system arises from the antagonistic relations between capital and labour, and this determines not only commodity production for profit but also the function of the state in enforcing these class relations. It therefore follows that with the establishment of a classless, socialist society, the state will be redundant, and the machinery of government will be converted for the purposes of useful, democratic administration. This position will be established with the socialist capture of political control.

The capture of political control by the World Socialist Movement will establish the position whereby socialist delegates will be in control of the machinery of governments at local and national level throughout the world. Their first action will be to implement the common ownership of the means of production. Classes will thus be abolished and a classless community come into being.

Since state machines operate on the basis of class-dominated society, it follows that they can have no place in a classless society which will be democratically organised solely for the needs of the whole community. The present system of centralised government decision-making which is enforced by the state apparatus will be abolished and replaced, with the establishment of socialism, by a democratic system of decision-making in which decisions would flow from the broadest possible social base as representing the democratic views of the whole community. The particular functions which now comprise the machinery of governments will become redundant or will be retained according to their usefulness to the needs of the community. As well as this of course, new functions would be necessary.

The operation of states consisting of centralised political executives imposing their decisions on society through a coercive state apparatus, according to class interests, would therefore be automatically swept away. Concerning particular functions, it is obvious that such a government ministry as a Ministry of Defence, together with all armaments production, would also be immediately redundant. The government bureaucracies concerned with tax gathering, allocation of funds, payments of pensions and other monetary allowances, accounting, rates, etc, are also obvious examples which would be redundant. On the other hand, existing government departments at national and local level concerned with housing, education, transport, health, roads, energy supply, communications, or any body which could be usefully concerned with social safety, would need to be retained, adapted or expanded as part of the democratic system concerned solely with administration for needs.

(Part 2)

I. The state of capitalism

The popular conception of the state is that of a kind of neutral pendulum which can be swung in different directions in accordance with the philosophy of the dominant political party. In other words, that the degree of authority which the state institutions wield, the levels and methods of coercion and oppression which these institutions employ in practising this authority, and whether this authority is put to “good” or “bad” purposes (e.g. whether it is used to inaugurate or maintain a “Welfare State” or a police state dictatorship) is determined by the aims and aspirations, or indeed, sometimes even by the personalities within the party which constitutes the government.

To a certain extent this is true. Outwardly, the modern state takes many different forms, and is coercive and oppressive to varying degrees. The totalitarian state, whether of the “left” or “right”, is undoubtedly more oppressive than the “democratic state” in as much as those who control it (regardless of how they came to do so) have to rely more heavily on the services of the police and army, the political allegiance of its “officials” and subjugation of its citizens.

To view the state merely as a passive, autonomous body, ready to be put to the service of “good” or “bad”, to be steered in the “right” or “wrong” direction or to be manipulated at will by political philanthropists for the benefit of the population, or by tyrants for the benefit of themselves, is to imagine that the state exists in a kind of social and political void. It is to accept the assertion that the state (i.e. the armed forces, police, legal system, civil service, etc.) acts in isolation, uninfluenced by the social conditions and social relations within which it operates.

No matter what its form, or how its government is chosen, the state does not, and can not, act in isolation. It is a machine for the domination of one class by another, an instrument of class rule, and therefore can not be neutral, passive or independent.

ORIGIN OF THE MODERN STATE

The modern capitalist state with its armies, its police forces, its laws, rules and regulations for the defence of property, did not appear suddenly overnight. Neither is it the reflection of some innate propensity of the human race to be aggressive and unco-operative, as the more “holy” apologists of capitalism maintain. The state has neither a natural nor unnatural existence; it is the product of class conflicts, and as such, it has been forged in the social furnace of the three great epochs of class-divided society, chattel slavery, feudalism, and finally the world-wide system of society which we know today, capitalism.

It was the division of society into classes — a property owning minority and a propertyless majority — which gave rise to the need for the state. For, in order for the dominant class to maintain its property rights and to appropriate the surplus product of the dominated class, it was essential that it had at its command a coercive apparatus to enforce its laws and regulations. This coercive apparatus, consisting of a certain group of people set apart from society and engaged solely in ruling, administering, subjugating and oppressing in the interests of the monopolising class, is called the state.

As the social relations of equality and freedom (arising from the common ownership of the instruments of production) of primitive society were eroded, and replaced with the new class relations of owner/non-owner, exploiter/ exploited, robber/robbed, the need for the minority class of property owners to develop and maintain a permanent apparatus of coercion took root. Chattel slavery which evolved from primitive society, was the first definite form of class society, and it is in this epoch in which we find the embryonic form of the modern state. After chattel slavery came feudalism, in which the class relations changed from that of slave-owners and slaves, to feudal landlords and peasant serfs. The class rule of a minority did not change, however, and the consequent domination and dependence of the majority of people in society remained.

CAPITALIST FREEDOM

Historically, just as chattel slavery gave way to feudalism and ushered in the rule of the class of landlords, so feudalism gave way to capitalism and inaugurated the rule of a new class of exploiters — the owners of capital. As world trade developed on an increasingly grand scale and the circulation and power of money grew with the exchange of commodities, the capitalists superseded the power of the feudal landlords and became the new ruling class. This economic revolution, in which the capitalists instigated their own mode of production, did not involve the disruption of the state to any great degree, as the function of the state is to protect property, irrespective of who owns it or whether that property is composed of land, people, factories or machinery.

As capitalism advanced against the feudal system and became decisively established, so also did the social conditions and relations which enabled it to flourish. Capitalist society proclaimed the new ideals of freedom, liberty and equality for everyone before the law. It proclaimed the right of property ownership to be the right of every member of society. And it maintained that the dark old days of slavery and serfdom, in which “the sword ruled without shame and club-law prevailed”, when the division of society into classes severed the majority from the means of life and subjected it to the tyranny of a minority class of parasites, were no more.

Capitalist society declared that the state had miraculously conjured away the reasons for its own existence and had been transformed from an instrument of domination and coercion into the guarantor of this new-found liberty and freedom. Such were, and still are, the ideals of capitalist society. The reality for the majority of people was, and still is, very different. Even a momentary glance at the history of capitalism should suffice to convince any member of the working class who has emerged from the capitalist indoctrination clinics (schools, colleges, universities, to use their official titles) with their thought processes still relatively untwisted what this liberty and freedom meant in practice. “Liberty” meant the liberty of the capitalists to legally exploit and rob the new class of (wage) slaves, the working class. And “freedom” meant the freedom of the workers to starve if they didn’t fancy the idea of being exploited or robbed. Or, if they protested that “the game wasn’t straight” the freedom to be beaten, jailed or transported by the “guardians” of freedom — the laws and forces of the capitalist state.

From the time when the last peasant serfs were being forced from the land and herded into factories as wage-labourers up until the present-day, capitalism has not changed to any significant degree. Outwardly some changes have occurred, in that the capitalist system now dominates over almost the entire face of the earth, while its division into national segments has become more decisive. But the essential dynamic of capitalist production, the extraction of surplus value (profit) by means of the wages system, and the function of the state within each national segment in protecting property (regardless of the nationality of the owner) and perpetuating the rule of the dominant capitalist class has remained unchanged.

LEGALISED EXPLOITATION

In capitalism (including those countries like China and Cuba in which the ruling elite performs the role of private capitalists) society is divided into two classes. Those who monopolise the means of wealth production and distribution, i.e. land, factories, mills, offices, transport facilities and raw materials etc. (the capitalist class) and who constitute an insignificant minority, and those who own no substantial property (the working class) and who make up the vast majority of the world’s population. Capitalism is a world-wide system of production for profit. In other words, the capitalist class, as owners of the means of production, will only allow production to take place on condition that they can sell what is produced on the market to realise a profit. A number of things result from this, which render the exploitation of the working class and its oppression by the state, inevitable.

The fact that production in capitalism is geared towards making profits means the very foundations of capitalism rest on the exploitation of the working class. This exploitation of the workers in capitalism is accomplished by means of the “money trick” — the wages system. As the working class throughout the world has no substantial property of its own, in order to live its members have to sell their mental and physical energies (their labour power) to the capitalists in return for a wage or salary. In effect, this means the capitalist class has virtual control over the lives of the workers. The reason for this is that not only do the capitalists control the activities of the workers during the period for which they have bought their labour power (the hours of employment) but how the workers spend their “free” time is also almost entirely dependent on whether they are earning a wage or not, how much they earn, the number of hours they work, how hard and fast they are compelled to work and the nature of their work. In short, the lives of the workers are enslaved and shackled by the iron chains of capital.

After the capitalists have agreed to purchase the labour power of the workers, they set them to produce wealth in the form of goods or services. When this wealth has been produced however, it does not belong to the workers but passes into the possession of the owners of the means by which it was produced. The workers have no say in what happens to the wealth they have created, where it goes or who receives it, but merely receive a part of the value of this wealth in the form of wages and salaries. Of course, the capitalist class do not keep the wealth created by the workers for themselves. They have to sell it on the market, and, as the goal of production in capitalism is to realise profits, at a higher price than what their accumulated costs of production were. In this way the capitalist class is able to amass great fortunes, whilst the workers, who have to give back their wages to the class of capitalists as a whole when they buy the things they need to stay alive, are compelled to repeatedly sell themselves by the hour, week or month.

This legalised exploitation of the workers in the process of capitalist production is only the tip of the iceberg. Capitalism, because it is a system which puts the profits of a few before the needs of the many, oppresses hundreds of millions of people throughout the world by denying them access to the things which they need in order to live.

It denies tens of millions of men, women and children every year their right to life, by condemning them to systematic death by starvation, whilst at the same time destroying or discouraging the production of food, in order to maintain profit levels. In the “richer” countries capitalism lets people die of hypothermia and other curable diseases simply because the production and distribution of heating fuels, the building and equipping of hospitals and the developing and manufacture of medicines is manacled by the dictates of profitability. Production for profit condemns many more millions to the squalor of living in slums, yet building workers are thrown out of work in their thousands and rendered useless.

LAW AND ORDER IN PRACTICE

Irrespective of whether a government in capitalism is democratically elected or not, or whether it describes itself as Conservative or Communist, Social Democratic or Socialist, Labour or Liberal or whatever it is in office to run capitalism. Consequently, regardless of any good or bad intentions its members may or may not have had, it has no choice but to act against the interests of the working class, by wielding the forces of the state in the interests of capital.

Within each national segment of capitalism, the apparatus of the state, at every level, is staffed by personnel charged with the maintenance of the capitalist social order. This personnel comprises the police, army and navy, judiciary and legal system, prison staff, civil service and the “education” system, each in its turn, playing a part in making sure the working class constitutes a docile, indoctrinated and exploitable army of wage labour for the capitalists to feed off. “Ah!” protest the apologists of capitalism, “but they all play their part in maintaining law and order and ensuring that we can all sleep peacefully in our beds at night.” Indeed they do maintain “Law and order”, but what do these cherished words mean in practice?

Law and order means preserving stability in a society based upon class ownership of the means of life. It means people living on the streets of cities in every country in the world, because capitalism can’t provide houses for them. It means houses remain empty because it is “unlawful” for people to occupy them. It means that people throughout the world go hungry and cold because it is “unlawful” for them to take food and heating materials from the shops and stores. Law and order means the right of a minority class of parasites to monopolise the resources of the earth, and legally to rob and exploit the rest of the human race.

A society based upon production for profit requires a police force because it produces criminals, by forcing people to steal, rob and kill in order to live or in order to “prove themselves” in its jungle of social and political madness. The construction and building of armies and navies, far from being capitalism’s anathema, are its life blood, because it is a system divided into national segments, the capitalists of which are in constant conflict, a conflict which inevitably breaks out from time to time in open violence, over markets, resources, land and cheap labour forces from which they can wring their profits.

Capitalism needs “Law and order” to survive because it is riddled with contradictions and insoluble problems. It has long outlived its usefulness in the history of the human race and should be replaced with something new — socialism.

THE END OF THE STATE

Socialism will be a society in which there will be no place for governments, armies, police forces or any of the other oppressive institutions required by capitalism. In socialism the means of production and distribution of wealth will be held in common by society, enabling production to be carried on with the sole purpose of satisfying the needs of human beings. This means that, for the first time in the history of the human race, society will be in a position to eradicate forever the conditions of poverty, want, fear and insecurity, along with violent, aggressive beings which these conditions breed.

A society which caters for the needs of its members, because its members will be in control, will not need to set above itself a group of people to rule over it and dictate its actions. When all freely avail themselves of the wealth freely created there will be no need for policemen to stand guard over it to prevent people taking what they need from what they produce.

Socialism will not require the services of armies and navies because competition between the world’s population will be replaced by co-operation and an understanding that the material needs of people in one part of the world are the needs of people the world over.

Nigel McCullough

(Part 3)

2. A classless, stateless world

Running global human society without the machinery of states is regarded by some as being as unachievable as personal computer systems were to some people before their invention. Socialists observe that the coercive governmental machinery of the state has not always been a feature of human society but was created necessarily in a phase in our history and will, with equal necessity, be abolished with the establishment of socialism.

For the greater part of the history of human society social affairs have not been regulated by governments. The state arose from the need to keep class antagonisms in check. The economically most powerful social class becomes the politically dominant class through the state and uses its machinery as a means of holding down and exploiting the oppressed class. “The ancient state was, above all, the state of the slave owners for holding down the slaves, just as the feudal state was the organ of the nobility for holding down the peasant serfs and bondsmen, and the modern representative state is an instrument for exploiting wage labour by capital.” (Engels, Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State)

When the majority of men and women —the wealth producers — democratically act to put the means of life into the hands of the whole community there will no longer be a social need for the coercive machinery of the state. The majority of people will no longer have to suffer government by a minority. The government of people will be replaced by the administration of things. This will mean that the institutions now used by the state to keep the working class in check — the judiciary, laws, police forces and prisons — will become socially redundant. Similarly, the organised force used by the state to protect the interests of territories and markets of its wealth owners—armies, navies and air forces — will also become socially unnecessary. “The society that organises production anew on the basis of the free and equal association of the producers will put the whole state machine where it will then belong: in the museum of antiquities side by side with the spinning wheel and the bronze axe.” (Engels, Anti-Duhring)

Organising the world on the basis of a society in which people will contribute according to their skills and inclinations and take according to their self-determined needs is an attractive idea. A world society undivided by national boundaries and free from war and famine. A world society unfettered by the rationing system of money. Is it possible? Socialists contend that not only is the establishment of socialism immediately possible, but that it is an urgent necessity if we are to avoid the potentially horrific sorts of destruction which the continuation of capitalism would render probable.

There are several ways in which the practicability of socialism can be doubted but basically these doubts arise in three areas of inquiry. First, will “human nature” permit a classless world without government? Second, will the resources of the planet be sufficient to support a society based on producing goods and services simply to meet all human needs and third, do we have sufficiently advanced systems of communication, organisation and distribution to cater for running the world for all humanity?

MINORITY RULE NOT NATURAL

Does “human nature” stand as a barrier to a world without governments? In answering this question, socialists would draw a distinction between human nature and human behaviour. There are a few characteristics of humans which could be described as “natural” in the sense that they are anatomical or physiological features of all people irrespective of the social system that they live in. Reflex actions, like blinking to water the eyes, stereoscopical colour vision, bi-pedal locomotion, prehensile manipulation and so forth are examples of this sort of feature and they are relatively fixed characteristics. Also, of course, the needs for food, drink, clothes and shelter. Contrasted with this are a great variety of behaviour patterns which are socially learnt. Behaviour traits instilled in young people by families, the indoctrination of education systems and the aggression and murderous techniques taught by military forces are all examples of this sort of socially conditioned behaviour. In commercial society we are steeped in a competitive mentality from a tender age but this learnt behaviour conflicts with an essential characteristic of human society: that of co¬operation. As a society we are a highly integrated body of entities and we all rely upon one another. Our very advanced division of labour means that we are all, to some degree, mutually dependent and require each other’s co-operation even in capitalism. Because socialism will abolish classes — the relationship of employer and employee — and create a social equality of human beings, it will harmonise our social relationships with the way that we need to work in order to survive. It is worth observing that even in today’s competitive world we are all co-existing in an intricate network of co-operation. Picture the seething mass of work going on in one of today’s big cities — it would grind to a halt in one second without the continued and very complex co-operation amongst millions of people.

Primitive humankind co-operated for tens of thousands of years without government, but apart from this evidence that we are not organically predisposed to be ruled by a minority, there are many examples to corroborate the versatility of our nature. Anthropological examinations of Red Indian, Aboriginal and Eskimo societies all testify to the fact that we can and have organised society on a democratic basis. Many modern societies which organised themselves on a communistic, democratic principle (like the Kalahari Bushmen, or Kung people, of southern Africa) are now being sucked into the commercial, competitive world. They are being driven from the lands that they inhabit as it is “purchased” by developers, and are forced to seek a living by wage-slavery. Another example of this, occurring now, concerns the Panare Indians who live in the Orinoco basin in Venezuela. They have enjoyed life, until recently, in 38 communities living on the basis of “from each according to ability, to each according to need”. They have no divisions of class and no status discrimination on the grounds of age or gender. Ideas of competition and violence are entirely antithetical to them. Their stress-free lifestyle is now being shaken by an American airborne evangelical group, the New Tribes Mission. Their lives are being smitten with religious indoctrination and all sorts of sinister devices are being used to make them docile, ashamed of their lifestyles, and to go in search of employment in the local mines.

In a rat-race we do acquire rat-like propensities but even now they do not dominate us and more importantly, they are subject to change if and when we decide to abolish the sort of social environment which causes them.

SUFFICIENT MATERIAL AND HUMAN RESOURCES.

The latest United Nations estimate of the world population is 7.7 billion. Are the resources of the world enough to support everyone? Today there is a massive unmet social need as a result of a social system which only produces goods if there is the prospect of selling them on the market for a profit. These unmet needs range from the horrors of mass starvation (according to Oxfam 800 million men, women and children go hungry every day) and homelessness to the relative impoverishment of all the wealth-producers. Alongside these needs capitalism presents in all countries the conspicuous over-consumption of a small elite, lakes of wine and milk and mountains of food and gigantic resources being pumped into socially useless or destructive ends.

Military spending now totals trillions across the world. This greatly exceeds the resources needed to meet the United Nations targets (idealistic as they are under the profit system) of providing everyone with adequate food, sanitary water, health care and education. It is an unchangeable priority of states in capitalism to put the needs of the Death Industry before basic human requirements. In a socialist society all of the ingenuity, human effort and resources which are now pumped into militarism will be donated instead to producing goods and services which are useful and enjoyable. On a similar point, consider all of the materials and human resources which are spent today on the necessary workings of the commercial system which would be liberated in socialism to be devoted to more rewarding sorts of work. The millions of men and women who are today engaged in running the system that exploits them in banking, insurance, commerce, tax revenue, everything connected with the production and running of prisons and the police forces, would be freed to help take part in the task of providing the sort of things that people really want.

Julian Simon and Herman Kahn in their book The Resourceful Earth produce carefully researched evidence to demonstrate that the planet enjoys much greater resources than are currently being tapped. Their writing is, ironically, aimed at advocating a free market economy with minimal economic controls — the very principles which produce such great hardship now — but their evidence is nevertheless useful. As they observe, the scare-mongery about dwindling resources is not new. People have always been predicting that one or other natural resource will be exhausted. It was once a respected view that oil reserves would dry up in the 1880s. In practice these predictions encourage discoveries of new reserves or the development of new substitutes for the threatened material.

Capitalism only ever aims to produce on a scale matching what people can afford to buy, not what they actually need. For this reason many agricultural techniques are underdeveloped compared with our technological abilities.

ORGANISING A GLOBAL CLASSLESS SOCIETY

Do we have adequate systems of communication, organisation and distribution to operate a global classless society? As with the questions of “human nature” and the earth’s resources, the answer to this question is partly apparent now. Because it is necessary for capitalism’s international trade, the world is already a highly integrated network of communications, travel and distribution. In this sense, capitalism is pregnant with socialistic organisation. With its booms and slumps, shortages and gluts, disruptive wars and embittered industrial disputes, capitalism is a chaotic, anarchic social system. In socialism production and distribution will be democratically planned. Society will not be told by a minority that food cannot be produced because there is no market for it. We shall harness all of the technology that capitalism has produced, discover exactly what our needs are, and where, and then plan production to meet them. Computer systems, current electronic stocktaking devices used in supermarkets and the astonishing technology of communications and travel used today by military forces and banks will all play their part. And think how much easier it will be to simply find out how many people in what places need what goods, than the task of market researchers of discovering who might buy what in the uncertainties of the market.

Without nations and governments, how will this production be planned? The world administration for production for use will need to satisfy the requirements of historical continuity, practical necessity and democracy. That is, it will need to adapt existing social organisations, develop them in a way to deal with the practical problems which need to be solved and to permit democracy in all decision-making. Socialists are currently in a minority and it will be for a majority to make the final decisions about how socialism will work. We can however still make some practical suggestions today. Decision-making could operate on three sorts of geographical level: the local level (corresponding to current local government areas), the regional level and the global level. Decisions about social policy and planning, whatever the scale of their intended effect, would need to originate in a locality. They could be raised by individuals, groups or local representatives of a specialist global group, connected with, for instance, health or the ecology. A policy proposal intended to affect society generally would need to pass successfully through all three levels of decision-making and then be implemented at local levels across the world.

The decision-making process in socialism will be such that everyone will have access to any information they need to make the decision and the opportunity to express views on the issue to everyone else. In the age of advanced telecommunications and the teletext this will not present any significant problems. Decisions only affecting a locality will probably be participated in by people living or working in that locality and similarly with regional decisions. We could make great use of the various information-gathering systems and expert organisations which have been developed by capitalism. Take one example, the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. It is organised in 147 countries and has thousands of planners and technicians all over the globe. It produces scientific papers which collate research material from all over the world and maintains a library of knowledge on food, agriculture, forestry, fisheries, nutrition and conservation. Its research keeps a census of world agricultural resources.

Socialists propose the immediate establishment of a classless, global society based on the common ownership and democratic control of the means of living by the whole community. This sort of society can only be created by a majority of people consciously and democratically acting together to take on the responsibility of running the world for ourselves. Today’s reality is, very often, yesterday’s vision:

“It is a dream, you may say, of what has never been and will never be; true it has never been, and therefore, since the world is alive and moving yet, my hope is the greater that it one day will be: true it is a dream; but dreams have before now come about of things so good and necessary to us that we scarcely think of them more than of the daylight, though once people had to live without them, without even the hope of them.” (William Morris, The Lesser Arts, 1877)

Imagine there’s no countries, it isn’t hard to do

Nothing to kill or die for and no religion too

Imagine all the people living life in peace

You may say that I’m a dreamer

But I’m not the only one

I hope some day you’ll join us

And the world will be one.

(John Lennon, Imagine)

Gary Jay

(Part 4)

Notes on the State

Central to socialist thinking on the nature of the capitalist state is the concept of class. Drawing on the writings of Marx, socialists argue that we live in a class-based society, in which a small minority own and control the means of producing wealth to the exclusion of the rest of the population.

Specifically, we live in a society which is divided on class lines: the owners of capital, the capitalist class, and the sellers of labour power, the working class. This relationship between buyer and seller of labour power is necessarily antagonistic and this antagonism expresses itself from time to time in struggle over the distribution of the social product. Because of this socialists argue that the state cannot remain neutral — a passive observer of the class struggle. Rather we say that the state must intervene on the side of the economically dominant or owning class, because the state is controlled directly or indirectly by this class. This puts us at odds with the views of the “pluralists” who argue that power is diffused throughout a plurality of institutions in society and that the state is neutral in relation to the class struggle. But although it is possible to demonstrate the unequal division of power and wealth in society, and hence show up the crucial weaknesses of this theory, we still do not arrive at an answer to the central question of what makes the modern state capitalist.

DISSATISFACTION WITH CLASSICAL TEXTS

Ralph Miliband’s study, The State in Capitalist Society, that came out in 1969 signalled a general dissatisfaction in academic circles with the original Marxist writings on the state and this was reinforced in subsequent studies. It was concluded that Marx had not developed a coherent account of the nature of the capitalist state, particularly in regard to its role in the process of capital accumulation and the reproduction of capitalist social relations; indeed, that many of the references Marx makes to the capitalist state were contradictory and theoretically confused: at times he referred to the state as an instrument of class rule; and then, more subtly, as a social regulator moderating and channelling social conflict; again, he talked of the state as parasitic, that is, the private property of individuals; and, finally, as epiphenomenon (simple surface reflection) of a system of property relations and resulting economic class struggle.

The claim that the state is simply an instrument of class power used by the economically dominant class to dominate subordinate classes is highly problematical and (possibly) a-historical. Although the ruling class owns and controls the material and mental means of production, one cannot automatically assume that it thereby controls, runs, dictates to, or is predominant in the state as well. The ruling class is not a monolithic power bloc; it is fragmented, with differing and, at times, conflicting interests. Moreover, in certain historical circumstances, the economically dominant class has not held state power, for example, in nineteenth century Prussia where the aristocracy (the junkers) controlled the state although it was a declining economic force.

Numerous problems also arise with the view of the state as a factor of cohesion in society, regulating the struggle between the classes, either by repression or concession. The main difficulty with this approach is that it suggests that the conflict over the social product is resolvable, and if taken to its logical conclusion it precludes the possibility of revolution as the state, in its role as class mediator, can act to defuse crises arising out of the contradictions within the capitalist mode of production. It is also very much akin to the liberal view of the state as “nightwatchman”. Likewise, the parasitic approach can only lead to demands for a democratisation rather than the abolition of government and, perhaps, this is why Marx dropped references to it in his later writings.

The ephiphenomenon aspect of Marx’s views on the state is rooted in the metaphor of base and superstructure, that is, that the state in its legal and political forms is simply a reflection of the economic base of society. This implies that the state is a passive instrument in the class struggle or, at best, is a tool of the ruling class. To adopt such a position leads one either to the reductionism of the equation that class power equals state power, or, to ignore the role the state has played, and is playing, in organising the labour process and in creating the conditions for further capital accumulation. The epiphenomenon view thus places a straightjacket on the activities of the state, divesting it of any autonomy or freedom of action, something which is at odds with the historical development of capitalism.

Dissatisfaction with the classical Marxist texts on the nature of the state led to a reformulation of theoretical perspectives by a new generation of Marx students. The outcome has been by no means theoretically homogenous, in fact, a variety of perspectives have emerged which we will now attempt to synthesise.

RELATIONSHIP OF THE RULING CLASS TO THE STATE

In Marxism and Politics, Miliband offers three possible, but not necessarily interrelated, explanations concerning the relationship of the ruling class to the state. The first of these concentrates on the personnel of the state. Miliband argues that those who control the state share a similar or common social background and are linked together by economic and cultural ties. These links result in a cluster of common ideological and political attitudes, as well as common perspectives and values. Thus those who run the state apparatus are by virtue of their circumstances favourably disposed to those who own and control the economic means of life. Empirical evidence would tend to bear out some of Miliband’s assumptions. In The State in Capitalist Society, he provides an impressive array of detailed information which chronicles the interconnections between the elite groupings in society. The state is largely run by people from similar social backgrounds and educational establishments, in spite of numerous Labour governments and so-called working class occupational mobility. But this approach inevitably leads to the reductionism mentioned earlier as it does not explain how the state is capitalist. Crucially it does not amount to a Marxist theory of the state as it discusses the state in isolation from socio-economic forces. Miliband’s work serves only as a rebuttal to pluralist assumptions about political democracy.

To buttress the obvious shortcomings of this approach Miliband introduces an economic dimension to his analysis. This centres on the role of capital as a pressure group. Here capital, particularly “monopoly capital”, uses its position as the major controller of wealth and, hence, of investment to demand the ear of government. The fear in governing circles of multinationals redirecting investment and causing large numbers of job losses ensures that they listen sympathetically to them. In some accounts of this process, particularly that of Baran and Sweezey and the “Communist” Party, the state and monopoly capital become fused; the former acting as a pliant tool of the latter. These views ignore the fact that the state often acts against the interests of certain sections of the capitalist class. The state passes reforms in the social and economic fields which capital dislikes, for example, high levels of unemployment benefit and spending on welfare services in general. Moreover this approach reduces the state to an epiphenomenal position, that is, the nature of the state is drawn from the immanent tendencies of capital accumulation. It also disregards the role of class struggle in shaping the way the state responds to certain issues and problems.

HOW CONSTRAINING ARE THE CONSTRAINTS?

The problematic nature of the above approach and its corollary that small and medium size capitals should unite with the working class in a struggle to overthrow monopoly capitalism has been severely criticised by “structural Marxists” such as Althusser and Poulantzas, and this leads us to the third explanation offered by Miliband. Structuralists argue that “the state is an instrument of the ruling class because given its insertion in the capitalist mode of production (CMP) it cannot be anything else”. Thus it matters little who constitutes the personnel of the state, or what pressure is exerted by capitalists, as the actions of the state are determined by the “nature and requirements of the CMP”. In other words, a capitalist economy has its own logic or rationality to which any government or state must sooner or later submit, regardless of its ideological or political preferences; the existence of the capitalist mode of production constrains the state to act in ways favourable to the expansion and preservation of the economic system and against the interests of the working class.

The structuralist view has been further refined by the work of the “capital logic” school of Berlin. This approach derives the character of the capitalist state from the categories of the capitalist economy, the process of production and accumulation. The state is seen as a political force which is required to secure the reproduction of wage labour—to the extent that this cannot be done through market forces—and to ensure the subordination of labour to capital. This requires the state to intervene in areas such as factory legislation, supervision of trade union activities and social welfare. In this role the state is prepared to act not only against the working class, but also against individual capitals or fractions of capital which threaten the interests of capital in general.

Although it has a persuasive logic to it the structuralist view has a number of crucial weaknesses. Firstly, how constraining are the constraints? If total, then the outcome of that totality is economic determinism, as it would lead to a situation where human beings are deprived of any freedom of action or choice. Man however is not simply the product of economic forces, but a complex organism, whose actions are determined by many competing factors such as tradition, religion (where appropriate), altruism, nationalism, and so on. Secondly, and this follows from the first point, if we accept the structuralist position on the state, then we preclude consideration of how workers in struggle have affected the nature of the state and how it reacts to working class demands. In short, we could dismiss the last 150 years or so of the class struggle.

Similarly, the capital logic approach not only fails to account for the origins of the capitalist state, but fails to show convincingly how it can operate as the ideal collective capitalist. In short, how does it determine, and by what means, what are the “best” interests of capital? Moreover, in this scheme everything that occurs in a capitalist society apparently corresponds to the needs of capital accumulation, and even where modified by class struggle the interests of capital are always realised. The whole theory is deterministic, and can only provide a partial analysis to the central issue of what makes the state capitalist.

WHAT MAKES THE STATE A CLASS STATE

These explanations, although more systematic and coherent than some earlier Marxists’ writings on the state, fail to explain the central issue of what makes the modern state a class state: the state of the capitalist class. The main reason behind this is the reductionism of the approaches. This means that a more adequate theoretical approach is necessary; one which takes account of the actual historical development of the state and how this development has been influenced by the balance of class forces at specific historical moments, and appreciates that the state can and does enjoy a fairly high degree of autonomy and independence in the manner of its operation as a class state. After all if the state is to act in the interests of the capitalist class it must be free to come to a decision as to what actually constitutes those interests. In doing so it may have to favour one fraction of capital against another in order to preserve or promote the long or short term interests of the sum total of the system’s parts. This explains why particular social and economic policies are possible even though powerful economic groups are opposed to them.

This approach also allows for an account to be taken of the way the working class, through trade unions and other defence mechanisms, have affected the development of the state. For, given the nature of competitive capitalism, workers are forced to resist the encroachments of capital. The state must react in some positive way to workers’ (reformist) demands. Failure to do so would lead to civil strife and political instability. Thus state forms and institutions, without this in any way threatening underlying capitalist social relations, are partly the outcome of working class struggle and cannot simply be attributed to the interests of the ruling class or a mere reflection of the changing needs of the capitalist mode of production.

Socialists, then, do not accept the pluralist view that the state is the property of no single class and that because of this it responds to the demands of all sections of society. We recognise that the modern state is comprised of a flexible set of institutions which operate subtly and is, ultimately, the executive committee for the capitalist class.