Life and Times – What a contrast!

Last month’s column was entitled ‘What an example!’ and talked about a striking act of kindness and altruism by a young man working at a car wash (bit.ly/3Zjquze). Round about the same time as this happened, I happened to listen to a play on Radio 4, a drama-documentary on the 20th century American writer and social theorist Ayn Rand, who was renowned for praising and encouraging just the opposite forms of behaviour, that is selfishness and self-interest. The previous column mentioned how several hundred people responded in a strikingly positive way to my relating on my local community Facebook page what had happened outside the car wash. This substantiated the idea, much supported by many recent studies on the topic, that humans, given the chance, are a fundamentally cooperative species. But the Ayn Rand programme (it was called ‘Talk to Me’) showed a person not just doubting this idea but recommending a completely different form of behaviour among humans and being lauded by many with particular opinions on politics and society.

Greed is good

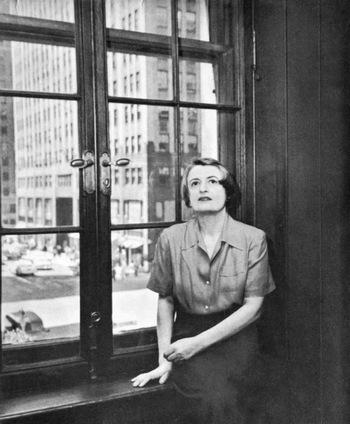

In ‘Talk To Me’, we found out how Ayn Rand’s Russian parents had been rendered destitute by the Bolshevik regime in the 1920s but had nevertheless managed to send her to America as a teenager for her education. When she left, she said she would become famous, and that’s what happened. She never returned to Russia but nursed an abiding hatred of its dictatorial government, and this fed into her entirely anti-collectivist, anti-cooperative theory of society which argued that all interaction should be conducted by what she called ‘rational self-interest’ and in practice meant advocacy of and dedication to the idea of a society governed by the free market with minimal state intervention. Initially Rand produced books of fiction which, though attracting little attention at first, later became famous and sold in their millions. Her two major novels were The Fountainhead (1949) and Atlas Shrugged (1957), the latter famously referred to as ‘the bible of selfishness’. These depicted heroic individuals who prospered or won out through egotistic behaviours regardless of any negative impacts their actions might have had on others. In fact, if the weak fell by the wayside, then this could only make the world a better place. For this kind of depiction, and through her later writings, Rand is often seen as the inspiration behind the slogan ‘greed is good’.

A gateway drug?

After these novels she focused largely on works of social and political theory putting forward what is often referred to as her philosophy of ‘objectivism’, whose essence is that a person’s individual happiness via ‘rational self-interest’ should be the moral purpose of their life and that any consideration of ‘society’ or altruism can only obstruct this (one of her books was entitled The Virtue of Selfishness). Rand’s ‘objectivism’ emphasised individual rights, including property rights, seeing laissez-faire capitalism as the only moral social system, because in her view it was the only system based on protecting those rights. And the radio play showed how appealing these ideas became to a significant number of people and how, in her later years, many – some of them high up in the US establishment – sat at her feet and venerated her. And even though she herself rejected the label ‘libertarian’, that has not stopped her becoming a kind of cult figure on the libertarian right of American politics. Historian Jennifer Burns has referred to her as ‘the ultimate gateway drug to life on the right’.

The radio play also showed how unsatisfactory this view of life and the world made her personal relationships, how she never seemed able to connect on a truly human level even with those closest to her. One scene, for example, showed how, when a close relative spent a significant period in hospital, she never visited, the implication being that to do so would not have served any purpose for her and would therefore go against her philosophy of a human being needing to put their own perceived happiness and pleasure before everything else. Given her view of egoism as virtue, should we be surprised that, in more recent times, she is mooted as Donald Trump’s favourite writer?

Car wash kindness

What a contrast then to what happened outside the car wash close to my home a short time ago. There a complete stranger chose to use his specialist knowledge to resolve in an entirely cooperative way a potential dispute between two drivers and then to adamantly refuse any monetary reward for what he had done. Then, following that, close to 700 people on social media took the time to congratulate him for his act of kindness and human solidarity. Instead of following Ayn Rand’s famous dictum that ‘altruism is evil’ and that all that counts is the interests of the individual (ie, yourself), he had chosen the opposite path, of kindness and collaboration, showing it to be a more ‘natural’, perhaps a more ‘instinctive’ human reaction. He refused to accept any material gain, but his gain was that he felt good about himself and no doubt good about seeing the approbation of his fellow human beings.

This kind of helpfulness and generosity without thought of material gain is something we see on a daily basis in so many interactions between people – and this despite the fact that we live in a system of society – capitalism – that has built into it an ethic of competition and individualism. Of course little of these daily interactions gets talked about or considered newsworthy in the information media, and this precisely because it is so common, normal and everyday. Rather what does get reported is the other kind of news, ‘bad news’, ie, those far less common instances of negative behaviour such as selfishness, unkindness, violence or ruthless maximisation of self-interest.

This is one of the things that socialists are at pains to point out in response to the common objection that the moneyless, wageless, free-access society we campaign for could not work because people are uncooperative, lazy, selfish, violent, etc. Well, actually, they’re not, and this is all the more reason why the society we advocate, based on cooperation not competition, would work. The coercion implicit in having to ‘get a job’ would go and human not monetary transactions would prevail.

HOWARD MOSS