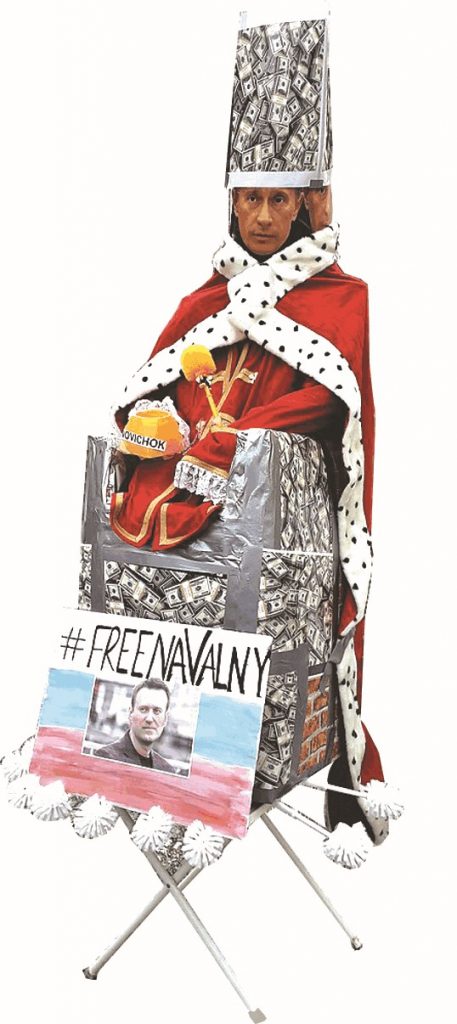

Anti-Putin Protests

It’s clear who they’re against, but what are they for?

What is the significance of the current Russian protests against the Putin regime? Western media have called them ‘unprecedented’. That is not so.

Mass protests are a frequent occurrence in Russia, though rarely do they attract much attention abroad. Many give voice to local grievances. This January, for example, residents of Ufa protested (successfully) against a big increase in heating charges. In 2019 there were mass meetings in Moscow against an urban renewal programme that threatened people’s homes – meetings larger (so a Russian correspondent tells me) than the anti-Putin protest. However, nationwide protest movements also occur, such as that in 2018 against a ‘reform’ to raise by five years the age at which people can start to draw a pension (43 percent of Russian men die before reaching the new retirement age).

Even focusing solely on protests organised by the anti-Putin opposition, today’s protests are similar in size and geographical scope to those that began in December 2011 and continued into 2012. Those protests were not on a large enough scale to have any chance of toppling the regime, nor are the current protests. They mobilise a much smaller proportion of the population (1 percent at most) than the opposition demonstrations in Belarus did last October (about 5 percent).

Enormous power potential

The Putin regime is not going to collapse any time soon. Its power potential is still enormous. It retains full control over TV – still the medium on which most Russians rely for information – and print media. Oligarchs connected with the regime (independent ones are no longer tolerated) own most of Russia’s natural resources and heavy industry. The state bureaucracy and armed forces remain loyal.

True, the regime has reason to be concerned about a gradual long-term erosion of popular support. Younger people have access to a wider range of information through the internet and social media. Tens of millions have watched the opposition video Putin’s Palace, about the president’s luxurious residence on the Black Sea coast.

Polls show that Putin’s approval rating has fallen over the last couple of years to about 60 percent, which is considered too low. This too, however, is not unprecedented. It hovered just above 60 percent from 2011 to 2013. Then in 2014 confrontation with Ukraine bumped it up to 85—90 percent. The annexation of Crimea was especially popular. No doubt the remedy of ‘a short victorious war’ – first recommended as a means of ‘averting revolution’ by Tsarist interior minister Vyacheslav Plehve in 1904 – can be applied yet again.

Nature of the ‘Putin regime’

But what is this ‘regime’ that Putin has established in Russia?

The Putin regime is neither a democracy nor an out-and-out dictatorship. It is officially described as a ‘guided democracy’. It can be represented as three concentric circles:

• at the core: Putin, his presidential administration and government, and his loyal ‘party of power’ – United Russia (the opposition calls it ‘the party of crooks and thieves’);

• the ‘intra-system opposition’ of parties that accept Putin as president but advocate their own policies within permitted limits. There are at present three such parties: the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF), Zhirinovsky’s ultra-nationalist Liberal-Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) and Just Russia, a ‘social-democratic’ reform party that belongs to the Socialist International;

• the ‘extra-system opposition’ of parties and groups that oppose Putin, including Navalny’s ‘Russia of the Future’ (formerly the Party of Progress). Refused registration, they operate under duress and are unable to contest elections.

The term ‘opposition’ is therefore ambiguous. In its broad sense it refers to the intra-system as well as the extra-system opposition, in its narrow sense only to the extra-system opposition.

Uniting the opposition

Uniting the opposition

The political situation in Russia has changed in one significant respect. Nine years ago the extra-system opposition was deeply divided, as we reported in the Socialist Standard (Material World, July 2012). The three main components of the movement were Russian nationalists, Western-type liberals, and leftists of various sorts. Opposition rallies were enlivened by verbal and even physical clashes between nationalists on one side and anarchists or gay activists on the other.

These internal conflicts have been resolved, mainly due to the rising influence of so-called ‘national democrats’ who claim to combine Russian nationalism with Western-type liberalism. Alexei Navalny has played a central role in this development. Leftists have been marginalized within the opposition or have abandoned the movement. A group of anarchists and anarcho-syndicalists recently issued a declaration in which they renounce:

‘all participation in the political spectacles organised by supporters of the right-wing populist Navalny, sadly renowned for his openly nationalist attacks on immigrants, people from the Caucasus and Jews. Whatever excuses or ‘explanations’ may be offered, joining in their demonstrations would mean turning into an appendage of one of the political gangs waging a dirty and unprincipled struggle for power’ (bit.ly/3phllol).

Since 2019 Navalny has urged his supporters to vote ‘smart’ – that is, tactically – for the strongest opposition candidate standing in any election, even if that candidate is a ‘communist’ or one of Zhirinovsky’s people. Tactical voting will tend to strengthen the oppositional character of the intra-system opposition and narrow the gap between the intra-system and extra-system oppositions.

Who is Navalny?

Katya Kazbek in The Grayzone says that Navalny is ‘first and foremost … an investigative journalist’ who exposes corruption within the Putin regime (bit.ly/3amqo2J). This is certainly the centrepiece of his public activity. However, the investigations on which the anti-corruption campaign relies have for some time been conducted mainly by researchers at his Foundation for Fighting Corruption rather than by Navalny personally. Is fighting corruption an end in itself for Navalny? Or is it an instrument in his bid for power? It is hard to think of any other theme that would be equally effective in bringing diverse elements together in a broad coalition. Who, after all, is in favour of corruption?

This does not mean we can assume that a regime led by Navalny would prove any less corrupt once he came to power. Navalny has himself been convicted for fraud in his business dealings, though he calls the charges ‘frame-ups’.

Navalny is not only a public speaker but also a prolific blogger and video star who exploits social media to the full. He has a characteristic ironic style and sense of humour.

What does Navalny stand for?

The cruel treatment of Navalny by the Putin regime has won him much sympathy and admiration. Nevertheless, this should not bias our view of what he stands for.

Navalny’s constitutional proposals envision transition from a ‘super-presidential’ to a ‘presidential-parliamentary republic’ with an independent judiciary. His economic platform appeals to capitalists who lack close connections to the regime. He undertakes to transform the existing ‘twisted’ and ‘authoritarian-oligarchic model’ of ‘crony capitalism’ into a fully competitive model of capitalism with a level playing field and a strong high-tech sector. He promises to restart economic growth, ‘create a well-functioning pension system’, move towards an all-volunteer military, reduce crime, improve roads, transfer authority and taxes to the regions and municipalities, and stay out of wars abroad.

Not all of Navalny’s slogans seem compatible. For example, is it really possible to ‘fight corruption’ but also ‘trust people’? And how will he fund all his programmes, including a doubling of state spending on healthcare and education, and at the same time cut taxes? He says he will do this by reducing spending on the security services and ‘bureaucracy’ – but that is easier said than done. Although he criticizes the extreme inequality of wealth in Russia, he does not back Just Russia’s demand to replace the current flat-rate income tax (13 percent) by a progressive tax (though he does want to make the property tax more progressive).

Closer examination suggests that not all of Navalny’s promises should be taken at face value. He highlights a promise to establish a minimum monthly wage of 25,000 rubles (£242.50 or $325), but further on we learn that this is a goal to be achieved by stages, the pace to be set by regional governments (bit.ly/3rQmzIW).

It is difficult to assess Navalny because he is such a master at projecting different versions of himself at different audiences (an essential skill of any good politician). Facing west, he poses as a champion of human rights and condemns Russia’s ‘aggression against Ukraine’. But he is unwilling to give Crimea back to Ukraine. And he shares Russian nationalist ideas that militate against full recognition of Ukraine’s sovereignty – the perception of Russians and Ukrainians as constituting a single nation and the concept of a ‘Russian World’ that extends to Slav areas beyond state borders but does not encompass the Northern Caucasus, which he proposes to sever from the Russian Federation.

Dehumanising ethnic minorities

Most alarming, however, is the internal aspect of Navalny’s nationalism. Of course, the Putin regime itself is nationalistic. But Putin’s is a state nationalism. Navalny’s is primarily an ethnic Russian nationalism. He demands the full assimilation of ethnic minorities: those who wish to live in Russia ‘must become (ethnically) Russian in the full sense’.

Navalny’s main targets have been the Moslem immigrants from Central Asia (above all, Tajikistan) and the Caucasus. They originally came to Russia to earn some money and return home, but increasing numbers have settled in Russian cities, where they have been allowed to build mosques. Even though they do the hardest and dirtiest jobs, they are widely hated and abused. Their position resembles that of Hispanic immigrants in the United States. Like Trump, Navalny has taken full advantage of anti-immigrant sentiment.

In April 2017 Shaun Walker interviewed Navalny for The Guardian. To quote Walker:

‘Several years ago, he released a number of disturbing videos, including one in which he is dressed as a dentist, complaining that tooth cavities ruin healthy teeth, as clips of migrant workers are shown. In another video, he speaks out in favour of relaxing gun controls, in a monologue that appears to compare migrants to cockroaches.

I ask him if he regrets those videos now, and he’s unapologetic. He sees it as a strength that he can speak to both liberals and nationalists. But comparing migrants to cockroaches? ‘That was artistic license,’ he says. So there’s nothing at all from those videos or that period that he regrets? ‘No,’ he says again, firmly’ (bit.ly/3pe0YZf).

Another example of Navalny’s dehumanization of ethnic ‘enemies’ came during the 2008 invasion of Georgia, which he enthusiastically supported. Indulging in a play on words, Navalny called Georgians (gruziny) rodents (grizuny).

Russia in Western media

We can conclude by agreeing with the remarks of Katya Kazbek concerning how Western media cover events in Russia (as well as in other countries regarded as adversaries of the West). ‘The overwhelming majority of Western journalists,’ she observes, ‘are busy communicating their own narrative, which does not have anything to do with the real situation on the ground’ but ‘too often reflects the opinions’ of NATO governments. It is therefore ‘misleading and dangerous to judge Russia by what you hear most often about it’.

STEFAN