Proper Gander: Whatever Happened To Political Drama?

The phrase ‘cops ‘n’ frocks’ has been used to sum up the current state of British TV drama, with its lazy reliance on crime (Happy Valley, Silent Witness etc.) and the past (Call The Midwife, Downton Abbey). The range of dramas has narrowed considerably from previous decades, and the idea of televised drama being used to voice radical political ideas or critique social trends is sadly now more old-fashioned than a cathode ray tube.

From the 1960s, many plays found their homes in anthology series, a format which is as obsolete as political drama itself. Theatre 625 (1964 – 1968) featured dramatisations of The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists and works by George Orwell, August Strindberg and Franz Kafka. More widely remembered are The Wednesday Play (1964 – 1970) and its successor, Play For Today (1970 – 1984). Their emphasis was on original screenplays rather than adaptations, and therefore they concentrated on more immediate issues which otherwise might not have received much public attention. Around 600 plays were produced in these three BBC series, many of which were lost when their tapes were wiped in the belief that they had exhausted their economic potential. Notable productions include two plays about homelessness written by Jeremy Sandford, who slept rough as part of his research: Cathy Come Home (1966) showed a young family’s downward spiral into homelessness, while Edna The Inebriate Woman (1971) followed a woman’s life on the streets and in hostels, prison and a psychiatric hospital. The Spongers (1978) showed the devastating effects of welfare cuts on services for disabled people. The Black Stuff (1980) by Alan Bleasdale told the story of five Liverpudlian tarmac layers whose struggles with unemployment were subsequently described in its sequel series The Boys From The Blackstuff (1982).

As well as Bleasdale and Sandford, other prominent film-makers included director Ken Loach, producer Tony Garnett and writer Jim Allen. Outside the anthology strands, Loach worked with them on The Rank And File (1971), based on the Pilkington Glass strike which took place in a climate of trade union leaders being seen as too close to a government proposing laws against unofficial strikes, Days Of Hope (1975), which followed a family in the years after the First World War, and The Price Of Coal (1977) about a Yorkshire colliery community.

These plays are remembered as being ‘gritty’, focusing on hardship and aiming for realism by being filmed as if they were documentaries. However, the anthology format allowed for differing styles and messages, and even Ken Loach made an offbeat musical for The Wednesday Play. Other BBC series were thought experiments offering ‘what if…’ scenarios about possible drastic changes to society. Doomwatch (1970 – 1972) was set in a fictional government department which investigated threats from scientific developments, such as genetic engineering and behaviour modification. Distrust of the notion of scientific progress runs through Doomwatch like words in a stick of rock. ‘Progress’ has connotations of continual improvements, but science exists in a changing political and social context which shapes how it develops. In this series, politicians and scientists are depicted as secretive, self-serving and blinkered, suppressing awareness of unwanted side effects to further their own interests. Survivors (1975 – 1977) used the starting point of a pandemic wiping out most of the population to explore themes of replacing capitalist institutions, communal living and self-sufficiency. These dramas are less overtly political, perhaps because they aren’t based in real situations. The scenario described in nuclear war dramas The War Game (1965) and Threads (1984) fortunately hasn’t happened either, although these plays clearly criticised real-life government policies about preparing for and supposedly coping with armageddon.

Even children’s programmes occasionally tackled serious matters without talking down to their audience. Noah’s Castle (1980) was set in a near future where rocketing inflation leads to scarcity of basic commodities. The school-based Grange Hill (1978 – 2008) examined issues such as drug addiction and bullying as well as criticising the effects of funding cuts to education.

By the mid-‘80s, Grange Hill became less vocal about government education policies and Play For Today had had its day. Television drama was no longer a place to consciously voice political ideas, and instead the emphasis shifted to discussing more personal issues through soap operas such as EastEnders and Brookside. Soaps are more about juggling characters’ relationships than ideas, so the format doesn’t lend itself to exploring the impact of political and economic forces.

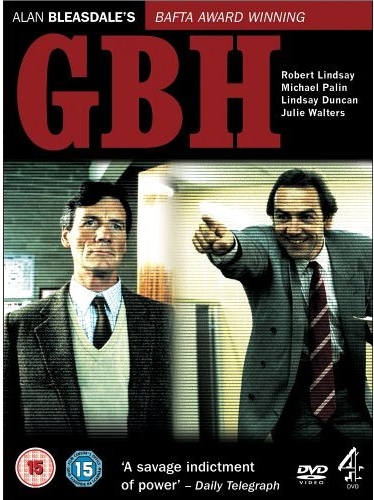

The mid-‘90s saw the final flowering of political TV drama. By this time, the documentary style of previous decades was going out of fashion, although the sense of anger remained. Cardiac Arrest (1994 – 1996) was a serial based on the experiences of writer Jed Mercurio when he worked in hospital. He describes a health service where staff have to rely on cynicism and cutting corners to cope with the hierarchies and impossible workloads. Our Friends In The North (1996) was Peter Flannery’s ‘state of the nation’ play, spanning thirty years in the lives of four people shaped by changing housing policy, police corruption and the miners’ strike. The plot of Alan Bleasdale’s GBH (1992) echoed events in the early ‘80s when Militant influenced the Labour Party and Liverpool city council. The other political dramas of the 1990s also had their roots in previous decades; Tony Garnett was an executive producer of Cardiac Arrest, and attempts to bring Our Friends In The North to the screen began since it was performed as a stage play in 1982.

All these plays passionately examine how people with little power or influence react to wider economic and political forces. They tend to be from a left-wing, rather than a revolutionary viewpoint, but still present experiences and situations from which we can draw our own conclusions. Why is television no longer an outlet for this kind of expression? These days, the BBC doesn’t want to alienate the government in case this leads to further funding cuts. It places more weight than it used to on its supposed ‘impartiality’. Any programme which presents a different viewpoint to acceptance of the status quo would be seen as ‘partial’, and therefore would not be produced. Even documentaries which expose injustices and corruption presuppose that the basic set-up of society is sound. This doesn’t mean that successors of Loach, Garnett, Allen and the others are clamouring to make political dramas and getting knocked back by conservative TV executives. What few successors they have probably realise that it’s not even worth trying.

MIKE FOSTER