How democratic is ‘Democracy’?

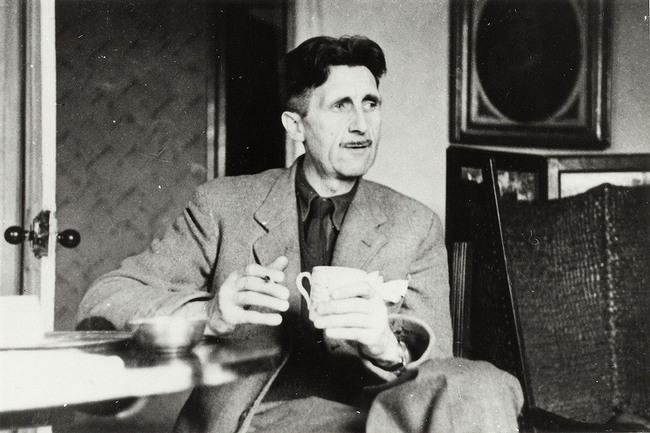

Writing in his 1946 essay, Politics and the English Language, George Orwell made the following remark about democracy:

Writing in his 1946 essay, Politics and the English Language, George Orwell made the following remark about democracy:

‘In the case of a word like democracy, not only is there no agreed definition, but the attempt to make one is resisted from all sides. It is almost universally felt that when we call a country democratic we are praising it: consequently the defenders of every kind of régime claim that it is a democracy, and fear that they might have to stop using that word if it were tied down to any one meaning’.

As Orwell noted 78 years ago, democracy is felt to be a political system that is good, and therefore when people wish to imply that a political system is good, they call it democratic. The question of democracy, however, like all political buzzwords, is in need of detailed and sober scrutiny by socialists, both for its connection with the capitalist society of today, and with the future socialist society to which we aspire.

Democracy in context

In considering democracy, we must be clear not to confuse fact and fiction. The ideas of the age do not represent reality, but are just that: illusions we tell ourselves (or are told about ourselves by others). As Marx and Engels cautioned in The German Ideology, we must not allow the ‘idea’ to become the ‘active force, which controls and determines [our] practices’. In this sense, socialists do not believe in democracy in the same way we do not believe in god.

In speaking of democracy we are thus talking not about a philosophical ideal, a utopian vision towards which we should be constantly striving, but an actual system existing in reality. It is not the job of socialists to perfect ideas, but to critique ruthlessly all that exists.

Democracy is often said to have originated with the Ancient Greeks. Certainly ideas of voting and the consent of the governed have existed throughout history. However, we must remember that for most of its history, democracy in the form of voting has been merely a method of sharing power between members of the ruling class. Ancient Greece was the democracy of slaveholders, and the English Parliament was the democracy of landlords.

It was not until 1832 that the vote in Britain began to be extended – rising from 1 percent of the population to 7 percent. Universal suffrage was not achieved until 1928, after a political conflict lasting over a century to fully extend the vote to working-class men and women. In America, blacks were excluded from voting until the 1960s under Jim Crow laws. Swiss women did not gain the right to vote in federal elections until 1971.

For most of its history, therefore, democratic forms of government have gone hand in hand with highly repressive and authoritarian political systems, in which the majority of the population have been prevented from voting even under republics and parliamentary governments.

How democratic is democracy?

The current form of democracy – liberal democracy – is based upon an idea of a separation between the private sphere and the public sphere. The public sphere is the realm of politics, civil rights, law-making; the private sphere is that of economic transactions between free individuals. At the risk of oversimplifying, we may say that Enlightenment philosophers such as Thomas Paine and John Locke saw a free society of individuals based on mutual agreement as the natural state of humanity. To them, the public sphere of states and laws was a necessary mechanism where people surrender some of their natural freedom to join forces and protect themselves and their property by mutually submitting to a central authority, namely a government.

This idea lies at the heart of modern democracy: the bills of rights and written constitutions that exist in almost every country on the planet, limiting (at least in principle) the powers of governments, flow directly from this philosophical idea that Private individualism is good and natural whereas Public collectivism is at best a necessary evil.

What liberal democracy fails to address, however, is the power individuals hold over each other. Individuals do not exist freely in relation to each other on a level playing field; even without the presence of a state, inequality and injustice would still exist in any society where ownership and control over resources is limited to a single class. Under a class-divided system, freedom in practice means the freedom of ‘man to exploit man’. The ‘rights’ to own property and make contracts protected by constitutions mean, in practice, the right of the capitalist class to hold us hostage to their economic power. Marx wrote at length on this dichotomy between liberal democracy’s promise of freedom and its reality of class exploitation, for instance in On the Jewish Question:

‘Practical need, egoism, is the principle of civil society and shows itself […] as soon as civil society gives complete birth out of itself to the political state. The god of practical need and personal self-interest is money’.

Under capitalism, political democracy provides the fig-leaf of economic dictatorship.

Something worth fighting for?

Socialists look to the ballot as providing a secure way forward for the transformation of society and the dissolution of class distinctions. At the same time, however, we must not shy away from the uncomfortable realisation that democracy does not mean freedom. Far from it, the history of democracy shows that it is not only compatible with, but comfortably well-suited to, sustaining class dictatorship.

As the German Social Democrat legal scholar, Hermann Heller wrote in 1928:

‘Through financial domination of party, press, film, and literature, through social influence over schools and universities, [the rulers] are able, without using direct corruption, to influence the bureaucratic and electoral apparatus in such a consummate fashion that they preserve every democratic form while achieving a dictatorship of content.’

Hermann Heller died five years later in exile in Madrid. The Weimar Republic in Germany was overthrown by the Nazis, with the backing of Junker landowners and the big industrial bourgeoisie. Before all else, the Nazis ruthlessly suppressed the leftist SPD and the KPD; arresting their politicians, closing down the left-wing press, and ransacking the offices of trade unions.

Since the invention of universal suffrage, every person has one vote, and each vote is counted once. This does not mean that all votes are equal. Tthe capitalist class own the media, the movie studios, the printing presses, and they sponsor the universities and research institutes. They have far easier access to scholastic qualifications and government jobs, and unlimited publicity through advertising, pop culture, and news media to reinforce the sanctity of the capitalist mode of production. As Marx and Engels outlined in The German Ideology:

‘The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of mental production, so that thereby, generally speaking, the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are subject to it’.

There are no easy answers to how socialists should navigate past these obstacles. However, in grappling with difficult questions of democracy and class conflict, we must remember what is at stake. On the one hand stands a ruling class which history shows to be violent, amoral, and ruthless. On the other stands the mass of the world’s population, robbed of the value they create by this class, and living in or just above destitution, and ultimately, it is to end this that we fight. Not for the democracy of the ruling class, but for a socialist world free of exploitation and the violence its maintenance necessitates.

UTHER NAYSMITH

One Reply to “How democratic is ‘Democracy’?”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

One of the best Socialist Standard articles I’ve read.