Wood for the Trees: Hope

The only good news these days, it would appear, is no news. The rise and rise of populist fascism; the ever-broadening gulf between rich and poor; the degradation of the environment; the multiplicity of wars; all of this seems to leave little space for hope. Is all hope an illusion or is it essential for life to exist at all? Everything we do is motivated by the hope that it will achieve the desired result; without hope we would do nothing because nothing would always be the result of both action and inaction equally. But without some evidence that human agency can achieve the aims hoped for, it becomes an empty faith. Ironically the hope that its absence will bring about a level of contentment courtesy of complacency and cynicism is nothing more than a paradox – the hope that a lack of hope would be emotionally and rationally preferable is also a hope. Unless we are clinically depressed it would appear that we’re stuck with hope; and that being the case is there any evidence that ‘the glass is half full’ rather than ‘half empty’?

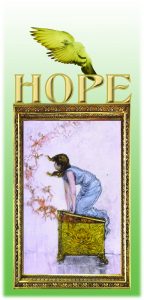

Famously when Pandora opened her box (jar) and released all of the evils into the world only one thing remained, after she had hastily closed it again, and that was hope. Since that time hope has had a deeply ambivalent quality; was it one of the evils within the box or was it the only incarnation of the good? Were we saved from hope by its imprisonment in the box or does it represent a positive resource preserved to enable us to face the evils? The hope for immortality in heaven and that karma will right the wrongs done to us are examples of the evil nature of hope since they are both represent the negative and impotent ‘triumph of hope over experience’. But does the hope that socialism represents the redemption of humanity also fit into this category? Certainly the ‘culture industry’ of capitalism ceaselessly endeavours to convince us that it does. It is very illuminating that our culture readily embraces a supernatural parental deity but finds the idea of a mature, rational and democratic society completely crazy! Let’s have a look at the hopes incarnate within capitalist ideology.

Happiness, we are told, depends on our ability to find someone to exploit our labour so that he can join the Freemasons and send his children to public school; it depends on us producing everything and then buying a tiny portion of it back to create profits and a ‘thriving’ economy; it depends on two weeks in a year where we get to work on our skin cancer under a ‘foreign’ sun; it depends on chaining ourselves to debt and mortgages; it depends on finding a ‘significant other’ that will give ‘meaning to our lives’ etc. Those who hope for these things deny the overwhelming evidence that all they bring is alienation, disappointment, bitterness and anger together with an early grave. The hope for the creation of a community based on mutual love and respect rarely features in the ‘bucket list’ of contemporary humans. This is the triumph of hope as a consumer durable with built-in obsolescence.

Socialism represents the antithesis to consumerism and its promise that if you have enough ‘stuff’ you will be happy; it offers a world where meaningful and fulfilling production for and within an egalitarian community provides for our most profound human needs. This is what socialists ‘hope’ for and believe in; it is not a faith because with faith you have certainty and with certainty there is no need for hope. We are well aware of the alternative which is barbarism; the fear that, as happened in Europe 1600 years ago, we are entering another Dark Age. Once it was thought that God would end the world because of its violence and injustice; today it is the Earth itself that will reject us by heating up and making human life unsustainable. Our species only just avoided a nuclear holocaust and we might never be that lucky again; those who say they cannot ‘wait’ for the revolution and want to do something ‘now’ are just prolonging the agony by promoting anti-revolutionary reforms.

Many in the past have been convinced of the imminence of some kind of ‘Armageddon’ and our contemporary fears are, in some ways, no different to theirs because since the development of private property societies and their violent parasitic elites there has always been much more room for despair and cynicism than hope. But there have also always been minorities who have courageously worked for a better future driven by the hope that humanity will turn its back on the tribalism of property and create a global community worthy of our potential – socialism.

WEZ