Book Reviews: ‘Role-modeling Socialist Behavior’, ‘Dancing With Dynamite’, & ‘In the Crossfire’

A socialist life

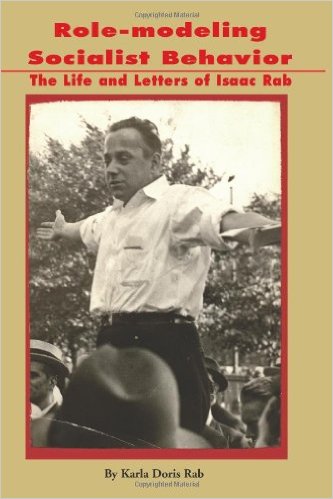

Role-modeling Socialist Behavior: The Life and Letters of Isaac Rab, Karla Doris Rab..Lulu.com. 490 pages.

This book is a worthy account of the life and works of one of America’s unsung working class heroes, Isaac Rabinowich, commonly known as Rab. Through the medium of his granddaughter’s personal account of Rab’s family life, it is particularly valuable to be able to view a Socialist such as Rab as a real person, tolerant and enlightened, not just a faceless propagandist. Well illustrated, this is a useful and thought-provoking book, carried out in a charmingly eccentric style.

This book is a worthy account of the life and works of one of America’s unsung working class heroes, Isaac Rabinowich, commonly known as Rab. Through the medium of his granddaughter’s personal account of Rab’s family life, it is particularly valuable to be able to view a Socialist such as Rab as a real person, tolerant and enlightened, not just a faceless propagandist. Well illustrated, this is a useful and thought-provoking book, carried out in a charmingly eccentric style.

The story of Rab is, in a sense, the story of real Socialism in America. Rab was born on 22 December 1893 in Boston, the old home of American ‘freedom’. His parents, Sheppie and Sarah, had recently arrived from the shetetls of eastern Europe but were literate and engaging, attributes which Rab inherited in spades. Rab also inherited his father’s socialist background, joining the Socialist Party of America at the age of sixteen. Despite his humble origins, Rab excelled academically and was accepted for Harvard. However, wanting to be a real worker rather than an academic drone, he headed instead to an agricultural college in Ohio. A chance flood destroyed his practical project and exhausted his financial resources, so, in the summer of 1915, he headed to Detroit, where a well-placed class mate acquired him a job at the Ford’s factory. Via the Detroit local of the SPA, he soon came into contact with Adolph Kohn and Moses Baritz, two SPGBers fleeing the effects of the First World War. The encounter was to change his life. Kohn and Baritz won Rab over to Marxism, to which he would dedicate the rest of his life.

On 7 July 1916, Rab and 42 other attendees of Kohn-Baritz classes established the Workers’ Socialist Party of the United States, along the lines of the Socialist Party of Great Britain. Faced with political repression, the group was to be short-lived and in 1919 was reconstituted as a social club known as the Detroit Socialist Education Society. Shortly after Rab was sacked by Ford for his political activities and moved with his wife and young family back to Boston.

The 1920s were difficult both politically and personally for Rab and it was not until the end of the decade that things began to move again. On a national level, comrades in New York began to issue a journal, The Socialist, Rab being one of the foremost contributors. Shortly thereafter, on 12 September 1930, the Workers’ Socialist Party was re-formed, with Rab a member of first Executive Committee. In Boston, Rab helped form a Socialist Education Society which in 1931 became the Boston local. It was around this time that Rab became friends with Anton Pannekoek, astronomer and Marxist theoretician, who stayed with Rab during trips to America. Rab was also on good personal terms with the council communist Paul Mattick.

In 1939, editorship of The Western Socialist, previously a journal of the Socialist Party of Canada, was moved to Boston because of fears that the paper might be suppressed due to the outbreak of the Second World War, it becoming a joint publication with the WSPUS. The following year, national headquarters was moved to Boston too. Boston remained the centre of WSPUS activity in North America for the next forty years.

Boston local continued its extensive social and political programme into the ‘40s, which were, perhaps, the golden age of the WSPUS. In 1947, confusion with the Socialist Workers’ Party, a Trotskyist organisation, caused the WSPUS to be renamed the World Socialist Party, a significant development which has spread throughout what is now known as the World Socialist Movement.

The 1950s, as in this country, were a period of rapid and steep decline for real Socialism. The WSPUS was dogged at this time by controversies over the ballot and violence. Rab and the Socialist stalwarts, however, carried on with same enthusiasm.

Better times came in the 1960s, with the revival of radical politics with the Civil Rights and anti-Vietnam War movements and the opening up of new media for propaganda activities. The US Party was particularly enthusiastic in its use of radio programmes.

Rab remained throughout his life an active trade unionist, latterly as a member of the International Typographical Workers Union. He died in 1986.

Details on how to obtain a copy, write: WSPUS, P.O. Box 440247, Boston, MA 02144, USA or email spgb@worldsocialism.org

KAZ

************************************************************

South American elections

Dancing with dynamite. Social movements and the State in Latin America. By Benjamin Dangl. AK Press. $12.

Anarchists and anti-parliamentarists are always pointing to the overthrow of Allende in Chile in 1973 as an example of how the ruling class will not accept defeat at the polls, not even by leftwing reformists let alone by the election of a majority of socialist MPs.

They are behind the times. The last 15 or so years have seen the election and survival of leftwing presidents in a number of South American countries (Bolivia, Venezuela, Brazil, Ecuador, Argentina, Uruguay and even Paraguay), some of them with programmes more radical than Allende’s. There was indeed an attempt to overthrow one of them (Chavez in Venezuela in 2002) but this failed due to popular resistance and the refusal of the armed forces to back it.

Of course this doesn’t show that the ruling class might not stage a coup in the event of a socialist election victory, but it does rather undermine the argument that elections can never be a way to win control of political power.

In this book, brought out by an anarchist publishing house, Dangl examines the relationship – the “dance” – between “social movements” (in favour of land rights, legalising factory occupations, getting amenities in shanty towns) and the elected leftwing governments. He argues that the social movements should not put up candidates themselves nor let themselves be dominated by leftwing parties; instead, they should maintain their independence and continue to employ “direct action” to try to get what they want.

However, he is unable to take up a strict anti-parliamentarist stance because he can’t deny the logic of the movements preferring a government that will help them to leaving political power in the hands of those opposed to their aims. None of the movements have, as Dangl is obliged to record, adopted this stance but have voted and even campaigned for the leftwing presidents.

The case for a mass socialist movement not taking electoral action is just as weak since this would be to leave the apparatus of the state in enemy hands. A socialist movement is no more likely to do this than the present-day social movements in South America have.

ALB

************************************************************

Revolutionary

In the Crossfire: Adventures of a Vietnamese Revolutionary. By Ngo Van. Eds. Ken Knabb and Hélène Fleury. AK Press, 2010.

This book preserves the memory of a part of the history of the class struggle that might otherwise be lost. The author, Ngo Van, was born in 1912 in a village in what was then called Cochinchina – the southernmost of the three sections into which the French colonialists divided Vietnam. He came to maturity at a time of social upheaval. Peasants rose up against landlords and tax collectors, workers struck against atrocious conditions (the death rate on the rubber plantations reached 40 percent a year), and demonstrators demanded independence from France. These rebellions, and their savage repression by the colonial regime, are vividly portrayed in the memoir.

The political groups involved in the upheaval were very diverse. The Stalinist Vietminh were active, especially in the countryside, but there were many other anti-colonial movements that were not yet under their control. In the cities there were also several Trotskyist organizations. Chance contacts and revulsion against the regimentation within the Vietminh drew Ngo Van to Trotskyism and in 1935 he helped to establish a new Trotskyist group – the League of Internationalist Communists.

The Vietnamese Trotskyists were caught literally in the crossfire, hunted down both by the Sûreté (French colonial security police), who tortured and jailed them, and by the Vietminh, who simply killed them. The author was one of the few who survived by escaping abroad. From 1948 until his death in 2005 he lived in France.

While earning a living as an electrician, he remained politically active. In retirement he wrote extensively, mostly on Vietnamese folklore and Vietnamese and Chinese history. Several volumes of his work have been published in French; this is the first to appear in English.

In France Ngo Van progressed beyond Trotskyism to council communism. Articles that he wrote in 1968 on Third World struggles and the war in Vietnam are included in the book and express a point of view very similar to that of the World Socialist Movement. The book also contains helpful background notes and many photos, sketches and paintings by the author, who besides his other talents was an accomplished artist.

STEFAN