PDF Art-Labour-and-Socialism-Morris

PDF Art-Labour-and-Socialism-Morris

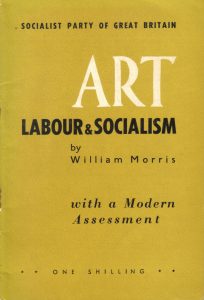

Art, Labour & Socialism by William Morris

With a Modern Assessment

Foreword

An address that William Morris delivered at University College, Oxford, was reprinted by him in the magazine Today, in February 1884, under the title “Art Under Plutocracy”.

In 1907 the larger part of it was published by the Socialist Party of Great Britain in pamphlet form as Art, Labour and Socialism.

It has long been out of print and we are issuing it again because, in the words of our Foreword to our original edition:

“It is not often that an accepted master in the arts can express himself with lucid brevity in the language of the common people; and even less frequently is that master able to scientifically diagnose the conditions of his own craft”.

“It is therefore the more refreshing to discover a work by an admittedly great figure in the artistic world which gets down surely to rock bottom facts, and in a style of quite charming simplicity establishes the connection of art and labour, and the conditions of labour which, after all—and however distasteful the information may be to the school of the ‘Intellectuals’—art is, in the final analysis, no more than a reflection”.

“We do not claim for Morris that he was always a convincing and consistent instructor in economics. Indeed, his work in this direction, regarded as a whole, entitles him to no more than a place in the category of the Utopians . . . But this does not blind us to the fact that Morris occasionally struck shrewdly at the pretensions of a vainglorious and shoddy intellectuality, placed art in its proper perspective, and did effective service by his unequivocal insistence upon the necessity, not only of passive working class discontent with, but active working class revolt against, the system of society that enslaves them, robs them of the results of their labours, and incidentally deprives them of that joy in the work of their hands which stands for him at the very foundation of art”.

Executive Committee

Socialist Party of Great Britain

February 1962

A Modern Assessment

I. Morris and His Work

Most of the writings about Morris concentrate upon his work as a poet, interior decorator, printer and designer of coloured glass windows, but neglect the other side of his activities: speaker, teacher, and writer about Socialism.

He was already an international figure in the art world when the poverty, squalor and ugliness that constantly confronted him led him to probe into the problem, and he began to take an interest in Socialism, and finally came to study Marx’s Capital.

He joined the Social Democratic Federation, which claimed adherence to Marxism, in 1881. However, he soon became dissatisfied with its reformist policies and its electioneering tactics. He left the organisation along with Eleanor Marx, Belfort Bax, Frederick Lessner (and old associate of Marx in the production of the Communist Manifesto) and Marx’s son-in-law Edward Aveling. They then formed the ‘Socialist League’ in 1884. Along with Bax he edited the ‘League’s’ Journal The Commonweal. In the first number of this journal, on the front page, there appeared an ‘Introductory’ by Morris and the ‘Manifesto’ of the League. The beginning of the ‘Introductory’ was as follows: – “We beg our readers’ leave for a few words in which to introduce them to this socialist journal, The Commonweal. In the first place we ask them to understand that the Editor and Sub-Editor of The Commonweal are acting as delegates of the Socialist League, under its direct control; any slip in principles, therefore, any misstatement of the aims and tactics of the League, are liable to correction from the representatives of that body. As to the conduct of The Commonweal, it must be remembered that it has one aim—the propagation of Socialism”.

This was certainly an innovation and a very promising start. A few paragraphs from the League’s ‘Manifesto’ will further indicate how far Morris and his associates had progressed in understanding:

“Fellow Citizens,

We come before you as a body advocating the principles of Revolutionary International Socialism; that is, we seek a change in the basis of Society—a change which would destroy the distinctions of classes and nationalities.

As the civilised world is at present constituted, there are two classes of Society—the one possessing wealth and the instruments of its production, the other producing wealth by means of those instruments but only by the leave and for the use of the possessing classes.

These two classes are necessarily in antagonism to one another. The possessing class, or non-producers, can only live as a class on the unpaid labour of the producers—the more unpaid labour they can wring out of them, the richer they will be; therefore the producing class—the worker—are driven to strive to better themselves at the expense of the possessing class, and the conflict between the two is ceaseless. Sometimes it takes the form of open rebellion, sometimes of strikes, sometimes of mere widespread mendicancy and crime; but it is always going on in one form or other, though it may not always be obvious to the thoughtless looker-on.

We have spoken of unpaid labour: it is necessary to explain what that means. The sole possession of the producing class is the power of labour inherent in their bodies; but since, as we have already said, the richer classes possess all the instruments of labour, that is, the land, capital, and machinery, the producers or workers are forced to sell their sole possession, the power of labour, on such terms as the possessing class will grant them.

These terms are, that after they have produced enough to keep them in working order, and enable them to beget children to take their places when they are worn out, the surplus of their products shall belong to the possessors of property, which bargain is based on the fact that every man working in a civilised community can produce more than he needs for his own sustenance.

This relation of the possessing class to the working class is the essential basis of the system of producing for a profit, on which our modern Society is founded.”

Although this was written so long ago, how well it fits conditions today, despite the claims that capitalism has changed and society has progressed. There is a further quotation from the ‘Manifesto’ which makes the comparison even more apt:

“Nationalisation of the land alone, which many earnest and sincere persons are now preaching, would be useless so long as labour was subject to the fleecing of surplus value inevitable under the Capitalist system.

No better solution would be that of State Socialism, by whatever name it may be called, whose aim it would be to make concessions to the working class while leaving the present system of capital and wages still in operation: no number of merely administrative changes, until the workers are in possession of all political power, would make any real approach to Socialism.

The Socialist League therefore aims at the realisation of complete Revolutionary Socialism, and well knows that this can never happen in any one country without the help of the workers of all civilisation.”

The last three paragraphs show how far in advance Morris was in relation to the Socialism in one country Communists, the Labour Party, and the multitude of reformers who misuse the word Socialism.

As this pamphlet shows, what was of abiding interest to Morris was to build up a Socialist system, devoid of wage-slavery and degrading toil, in which conditions would enable the producer to find joy in his labour, and would therefore enable him to make articles that were both useful and beautiful.

In Art, Labour & Socialism Morris had something worthwhile to say to his generation; we must consider now whether it is relevant to the conditions of today—and tomorrow. Some of the problems are examined in the following pages.

II. Has Machinery Lightened Labour?

In Art, Labour & Socialism Morris invited his readers to look at the purpose for which employers had used machinery. Like Marx before him, Morris agreed with John Stuart Mill who had written in his Principles of Political Economy:

“It is questionable if all the mechanical inventions yet made have lightened the day’s toil of any human being.”

Mill went on to say:

“They [machines] have enabled a greater population to live the same life of drudgery and imprisonment, and an increased number of manufacturers and others to make fortunes.”

One evil consequence of the introduction of machinery was that it increased the employment of women and children in the factories. Sir William Ashley in his work, The Economic Organisation of England (Longmans, 1921, page 161), wrote of this development:

“The new machinery rendered the work physically so light that it became possible to employ women and children in large numbers; and the sinking of capital in costly machinery made it seem in the interest of employers to work that machinery as continuously as possible. Neither the employment of children nor excessive hours were absolutely new phenomena. Both had been seen in the domestic workshop. But the employment of children was now systematised and extended on a vast scale; and excessive hours, instead of being an occasional episode, say once a week, became a regular thing, every day in the week.”

In the same year that Mill’s work was published, 1848, Marx and Engels had written in the Communist Manifesto:

“ . . . in proportion as the use of machinery and division of labour increases, in the same proportion the burden of toil also increases, whether by prolongation of the working hours, by increase of the work exacted in a given time, or by increased speed of the machinery etc.”

Marx, Mill and Ashley were writing of a period when machinery was taking away the livelihood of craftsmen and forcing them to work in factories under harsh conditions and for long hours. Since then, as the working hours of most workers have been much reduced and child labour in factories has been made illegal, we may ask to what extent the statements made by Marx and Mill in 1848 would be true today. We can accept that there are fewer workers doing jobs which involve heavy lifting, hauling, hammering, excavating and other hard physical effort, but along with a fairly general shortening of the working day and working week labour has been intensified, the speed of machines has increased (and with it the number of accidents) and more workers are compelled to perform monotonous repetition work which can be as tiring as heavy physical labour. It is the aim of employers to exact as much effort in the shorter working week as before, a fact making itself felt in the workers’ fatigue at the end of the day and the week.

The claim made in the early days of machine production that machinery lightens the labour and increases the comfort of the worker is being made now for automation; but again the high capital cost is leading to a worsening of conditions—this time in the increase of shift working. Mr P. G. Hunt of the Labour Relations Staff of the Ford Motor Company wrote about this in 1958. After claiming that with automation “almost invariably . . . the physical effort of the operator is vastly reduced or even completely eliminated”, he went on:

“A further factor that emanates from the high initial cost of automated plant is the need to recoup on capital outlay within a reasonable period, which can be achieved only by high utilisation of the equipment concerned. Such a recoupment in turn can be achieved only by longer hours, and longer hours mean shift working. . . . There is no denying the unpopularity of shift work particularly night work—with the majority of those who are called upon to operate it. It seems clear, however, that the trend towards such working must continue and increase, and that automation is at least in part responsible for this” (Financial Times, 1 December 1958).

Even the reduced hours of work are an illusory gain because, with the concentration of manufacture in big industrial areas, workers are compelled to travel longer distances between home and work.

Machinery has clearly failed to give that lightening of toil that it could have given and that economists and employers claimed in the early days that it would. We have an illustration of this in the picture that industrialisation presents to workers in less developed countries. Far from being invited to enjoy the prospect of having machines to lighten toil for them, and raise their standard of living with less effort on their part, they are being told by their leaders to be prepared to work harder: Mr Jomo Kenyatta, leader of Kenya Africans, hit on the appropriate phrase of calling on his followers to be prepared to work as hard as white men! (Daily Express, 6 November 1961).

III. The Employers’ Attitude to Machinery

We live in a world in which each day brings news of inventions and discoveries in the field of industrial machinery and methods; but not all of them are applied. Some never get beyond the stage of being tested; they are ideas that will not work in a practical way. But some which are proved to be technically sound and practical never come into commercial use. As it is put in a pamphlet on Automation: “Technically about every industrial operation could be made automatic but economically many are impracticable” (What is this Thing called Automation; published by ASSET). It is only the economically practicable ones that are of interest to employers, the ones that will increase their profit.

There could be no clearer illustration of this than the fact that employers, after installing new machinery, will even remove it if it does not pay. Over a century ago a Government Commission of Inquiry into the conditions of hand-loom weavers reported instances in 1834 “where employers gave up machinery and went back to hand labour as it was cheaper” (Industrial and Commercial Revolutions in Great Britain in the Nineteenth Century, Professor L C A Knowles. Second Edition, page 119). That happening in Britain in 1834 has its recent parallel in USA. The pamphlet on Automation referred to above relates how “In Cleveland, Ford management reverted to hand insertion of small liner bearings in the engine-block because automation of this process was uneconomical”.

What most commonly determines whether a new machine will be economic is the level of wages of the workers whom the machine will displace. It follows from this that variations of wage levels can cause machinery to be economic in one place and not in another and at one time and not at another.

Marx wrote about this in the eighteen-sixties:

“Hence the invention nowadays of machines in England that are employed in only North America; just as in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries machines were invented in Germany to be used only in Holland, and just as many a French invention of the eighteenth century was exploited in England alone” (Capital, Vol. I. Kerr Edition, 1906, page 429).

It is not labour-saving as such that the capitalist seeks, but cost-saving, and if for any reason wages are relatively low the capitalist will be quite content to carry on production by methods which employ large amounts of labour. As Marx put it, “Nowhere do we find a more shameful squandering of human labour-power for the most despicable purposes than in England, the land of machinery”.

It is the same in our own times. Machinery is manufactured in one country or locality where wages are low for use elsewhere in relatively high wage areas.

It was the scarcity of workers in rural areas of Britain and America during the two world wars that led to a great increase in the use of machinery that had been long available. Milking machines were being marketed for many years before labour-shortage caused them to be taken up in considerable numbers. The Encyclopaedia Britannica has the following on the use of these machines in USA: “The shortage and the high price of desirable labour for milking cows has extended the use of milking machine” (1950 Edition, Vol. 6, page 983). Even so it was estimated that in 1944, nearly 30 years after such machines were available, only 25 to 30 per cent of American dairy farmers used them.

Sometimes new machines are brought into use not because they directly save labour or cost, but because they give additional precision, which is of course indirectly profitable for the manufacturers selling the products of the machine in competition with other, less efficient products. And sometimes the gain is simply speed of production. It may be good business for a company to use machinery which is quicker, but the products of which are more costly, if by this means the products can be put on the market for quick sale, in advance of the cheaper but more slowly completed products of rival firms.

This is a particular example of a widespread waste that results from capitalist competition. The successful competitor who captures the market is not concerned that his success may mean the bankruptcy of unsuccessful rivals and the consequent breaking up of plant and machinery which could still be useful. When competition is keen it will induce profitable companies to scrap their own plant and machinery while it still has years of useful life before it in order to install costly improved machinery that will enable them to keep ahead in the race for markets.

The picture of capitalism’s use of machinery is hardly complete without reference to the construction of a £30,000 mail bag, power machine shop in Leicester Prison in November 1961, ending the years-long prison labour of hand-stitching. Mechanisation was needed “to meet the mail bag supply demands from the Post Office”.

IV. Socialism and Work

The establishment of socialism will bring far-reaching changes in production and distribution, flowing logically from the ownership of the means of producing wealth being transferred to the whole of society.

The products of labour will no longer be privately owned; incomes from property ownership and from employment will alike disappear, along with buying, selling, and profit-making.

In distribution the principle will be “according to need”, and, of course, without the double standards that now exist throughout the capitalist world, of best quality for the rich, and varying degrees of shoddiness for the poor; which, in turn, presupposes that in production every person will give “according to his or her ability” and will see to it that there are no poor quality goods turned out.

Unfettered access to educational and training facilities will enable all to acquire knowledge and skill and end the existing barriers between unskilled and skilled, manual and mental labour.

Great demands will be made on the productive capacity of society but there will be ample means of satisfying them. With the ending of capitalism enormous additional resources of men and materials will become available through stopping the waste of arms and armaments, and the innumerable activities that are necessary only to capitalism, including the governmental and private bureaucracies, banking and insurance, and the monetary operations that accompany every branch of production and distribution. On a conservative estimate this release of capacity will double the number of men and women available for the work of useful production and distribution. In addition, we may expect a continuing annual increase of productivity resulting from the accumulation of skill and knowledge and of productive equipment.

With these large additional resources at its disposal society will easily be able—if need be with some loss of productivity in particular fields—to end excessive hours of work, harmful speed and intensity, and unnecessary night and shift work, and to use machinery to replace human labour for types of work that cannot be other than unpleasant. This socialist policy will be a reversal of the capitalist policy applied in the nationalised coal industry, the head of which, Lord Robens, can declare that “there are literally thousands of jobs in industry which can give no satisfaction to the workers and never could” and can at the same time be increasing anti-social hours of work by pressing for shift working round the clock in order to avoid “expensive machinery” standing idle for a large part of the 24 hours (Times, 9 October 1961, and Sunday Telegraph, 9 July 1961).

Morris and Marx stated a positive attitude to labour, but before considering what they said it will be useful to examine the criticism that both were viewing the problem in relation to the ruin of craftsmanship by machinery, and that in the present century the problem is a different one and needs a different approach.

Marx and Engels, in the Communist Manifesto to which reference has already been made, wrote about the advent of machinery in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century:

“Owing to the extensive use of machinery and to division of labour, the work of the proletarian has lost all individual character, and consequently all charm for the workman. He becomes an appendage of the machine, and it is only the most simple, most monotonous, and most easily acquired knack, that is required of him.”

One critic of Marx was the late Henri de Man who published a study of machine work in Germany in the early nineteen-twenties, part of which was republished in England under the title Joy in Labour (George Allen & Unwin, 1929).

His criticism was that Marx drew a general conclusion about machine work based largely on the textile industries and that while that conclusion remained unquestionably applicable to “large strata of the working class . . . there are other strata to which the technical developments of the last eighty years have made it completely inapplicable, so that of them the reverse is true” (page 85).

Henri de Man’s two conclusions were that even under capitalism “the existence of detail work is not necessarily a cause of distaste for work” and that it is not impossible for skilled machine work to give the work full satisfaction even though much machine work fails to do so. We can accept both points, but they do not affect the validity of the general principle behind Marx’s words. Marx was not arguing that work with machinery is necessarily an evil. Like Morris, he recognised that it would be a positive gain if much unpleasant and degrading manual work was done by machines: as already mentioned, one of his charges against British capitalists was that they had failed to replace labour of that sort by machinery because it did not pay them to do so.

Following on the same train of thought Marx maintained that Socialism would do what capitalists had failed to do and that “in a communist society (*) there would be a very different scope for the employment of machinery than there can be in a bourgeois society” (Capital Vol I, Chapter XV, Section 2).

In a speech made in 1856 Marx had this to say of the possibilities of machinery: “Machinery, gifted with the wonderful power of shortening and fructifying human labour, we behold starving and overworking it”.

(*) In the middle of the nineteenth century Marx preferred to use the word communism because of the current misleading ideas associated with the word Socialism. Later on, he used the two words interchangeably to mean what the SPGB means by Socialism: which, of course, has no relationship to the misuse of the terms Socialism and Communism as applied to Russia today.

The central point of Marx’s criticism was that man should not be an appendage of a machine, doing monotonous work robbed of all individual character and charm, any more than he should be doing manual work of a like kind.

There are three principles that can be applied to work and production. The capitalist would like to have a working class which “lives to produce”; working class life being subordinated to the need of producing profit. A second attitude is that of many non-socialist workers and trade unions, that workers should “produce to live”; work being accepted as a necessary evil, to be kept to a minimum, and “life” to be lived in the leisure hours.

Marx and Morris took a third view, that the aim for a society of free men and women should be that work is part of life, no more to be neglected than other intelligently conducted human activities.

Marx, writing in 1875, stated his view with force and passion:

“ . . . when the slavish subordination of the individual to the yoke of the division of labour has disappeared, and when concomitantly the distinction between mental and physical work has ceased to exist; when labour is no longer the means to live, but is in itself the first of vital needs; when the productive forces of society have expanded proportionately with the multiform development of the individuals of whom society is made up—then will the narrow bourgeois outlook be transcended, and then will society inscribe upon its banners ‘from everyone according to his capacities, to everyone according to his needs’” (From Marx’s Criticism of the Gotha Programme, SLP Edition, page 9).

There is a certain irony in the situation that while many workers are content to accept tedious, repetition work as a necessity some employers have themselves discovered that its damaging effect on the workers is such that it does not pay. The Economist (2 December 1961), writes about this discovery:

“In the early years of scientific management it was presumed that the greater the breakdown of jobs into their component parts, the greater the efficiency. The trouble with this, however, was that men came to be treated as mere extensions to their machines. Today, industrial theorists have come to realise that beyond a certain point the simplification of work creates so many problems of boredom and dissatisfaction among workers that diminishing returns may set in. as a result, in many firms the pendulum has begun to swing back a little, and some tasks are being deliberately re-combined to make their execution more complex”.

It will be seen that Marx posed the same issue as did Morris. Is it still a real issue? Some people think that automation will abolish all work problems, and that we shall have workless production:

“Today our life is largely shaped by having to produce goods for our feeding, for our clothing, and so on. Suppose we could just turn on a spigot and have all these basic things just as we now have water?” (Robert Jungk, Guardian, 2 November 1961).

That idea came into the minds of many people (Robert Owen among them) in the early days of machinery; but for the foreseeable future it is a fantasy. Not that it would be technically impossible to build a factory operated by very few workers (this is an early possibility); but that is not production without workers, any more than the automatic telephone system or the driverless train system is production without workers. What has been going on for a century or more is the progressive elimination of workers from some manual operations, with simultaneous increased numbers of

machine-making workers in the metal, engineering and electrical industries and of workers in engaged on maintaining the machines. Overall, there is a continuing small net saving of labour, but no dramatic developments that would change the present dependence of production on human labour in some form or other.

What then should be the Socialist attitude to the issues posed by Marx and Morris? There is no doubt what the answer must be. In a free society, depending for its healthy functioning on agreement and voluntary co-operation, in which “the government of persons will have given way to the administration of things”, people will not wish to spend the working part of their lives as human automatons serving machines, any more than as human automatons performing monotonous manual operations. The principle must be that people in a Socialist society shall be able to bring to all the various aspects of life, including work, all qualities of body and mind, skill, knowledge, thought and imagination.

Arts, crafts and machine techniques will all have their place as Marx and Morris would have urged. The difference since their day is that powers and methods of production have become vastly greater and more varied; which means that man’s power to control the conditions of his life is correspondingly greater. He has potentially must greater freedom of choice and it is inconceivable that under Socialism man will decide to enslave himself to productive processes of his own making.

We are confident that the reader will find Morris’s work ideas worth thinking about, including that most important idea of all, that in order to get a better system of society it is necessary to get rid of Capitalism and establish Socialism.

Art, Labour & Socialism

By William Morris

Reprinted from Today

I am “one of the people called Socialists”; therefore I am certain that evolution in the economic conditions of life will go on, whatever shadowy barriers may be drawn across its path by men whose apparent self-interest binds them, consciously or unconsciously, to the present, and who are therefore hopeless for the future.

I hold that the condition of competition between man and man is bestial only, and that of association human: I think that the change from the undeveloped competition of the Middle Ages, trammelled as it was by the personal relations of feudality, and the attempts at association of the guild-craftsmen into the full-blown laissez-faire competition of the nineteenth century, is bringing to birth out of its own anarchy, and by the very means by which it seeks to perpetuate that anarchy, a spirit of association founded on that antagonism which has produced all former changes in the condition of men, and which will one day abolish all classes and take definite and practical form, and substitute Socialism for competition in all that relates to the production and exchange of the means of life. I further believe that as that change will be beneficent in many ways, so especially will it give an opportunity for the new birth of art, which is now being crushed to death by the money-bags of competitive commerce.

My reason for this hope for art is founded on what I feel quite sure is a truth, and an important one, namely that all art, even the highest, is influenced by the conditions of labour of the mass of mankind, and that any pretensions which may be made for even the highest intellectual art to be independent of these general conditions are futile and vain; that is to say, that any art which professes to be founded on the special education or refinement of a limited body or class must of necessity be unreal and short-lived.

“Art is man’s expression of his joy in labour.” If those are not Professor Ruskin’s words they embody at least his teaching on this subject. Nor has any truth more important ever been stated; for if pleasure in labour be generally possible, what a strange folly it must be for men to consent to labour without pleasure; and what a hideous injustice it must be for society to compel most men to labour without pleasure! For since all men not dishonest must labour, it becomes a question either of forcing them to lead unhappy lives or allowing them to live happily.

Now the chief accusation I have to bring against the modern state of society is that it is founded on the art-lacking or unhappy labour of the greater part of men, and all that external degradation of the face of the country of which I have spoken is hateful to me not only because it is a cause of unhappiness to some few of us who still love art, but also and chiefly because it is a token of the unhappy life forced on the great mass of the population by the system of competitive commerce.

The pleasure which ought to go with the making of every piece of handicraft has for its basis the keen interest which every healthy man takes in healthy life, and is compounded, it seems to me, chiefly of three elements—variety, hope of creation, and the self-respect which comes of a sense of usefulness, to which must be added that mysterious bodily pleasure which goes with the deft exercise of the bodily powers. I do not think I need spend many words in trying to prove that these things, if they really and fully accompanied labour, would do much to make it pleasant. As to the pleasure of variety, any of you who have ever made anything—I don’t care what—will well remember the pleasure that went with the turning out of the first specimen. What would have become of that pleasure if you had been compelled to go on making it exactly the same for ever?

As to the hope of creation, the hope of producing some worthy or even excellent work, which, without you, the craftsmen, would not have existed at all, a thing which needs you and can have no substitute for you in the making of it, can we any of us fail to understand the pleasure of this?

No less easy, surely, is it to see how much the self-respect born of the consciousness of usefulness must sweeten labour. To feel that you have to do a thing not to satisfy the whim of a fool or a set of fools, but because it is really good in itself, that is useful, would surely be a good help to getting through the day’s work.

As to the unreasoning, sensuous pleasure in handiwork, I believe in good sooth that it has more power of getting rough and strenuous work out of men, even as things go, than most people imagine. At any rate it lies at the bottom of the production of all art, which cannot exist without it even in its feeblest and rudest form.

Now this compound pleasure in handiwork I claim as the birth right of all workmen. I say that if they lack any part of it they will be so far degraded, but that if they lack it altogether they are, as far as their work goes, I will not say slaves, the word would not be strong enough, but machines more or less conscious of their own unhappiness.

* * * * *

The craftsman of the Middle Ages no doubt often suffered grievous material oppression, yet in spite of the rigid line of separation drawn by the hierarchical system under which he lived between him and his feudal superior, the difference between them was arbitrary rather than real; there was no such gulf in language, manners, and ideas as divides a cultivated middle-class person of to-day, a “gentleman,” from even a respectable lower-class man; the mental qualities necessary to an artist—intelligence, fancy, imagination—had not then to go through the mill of the competitive market, nor had the rich (or successful competitors) made good their claim to be the sole possessors of mental refinement.

As to the conditions of handiwork in those days, the crafts were drawn together into guilds which indeed divided the occupations of men rigidly enough, and guarded the door to those occupations jealously; but as outside among the guilds there was little competition in the markets, wares being made in the first instance for domestic consumption, and only the overplus of what was wanted at home close to the place of production ever coming into the market or requiring any one to come and go between the producer and consumer, so inside the guilds there was but little division of labour; a man or youth once accepted as an apprentice to a craft learned it from end to end, and became as a matter of course the master of it; and in the earlier days of the guilds, when the masters were scarcely even small capitalists, there was no grade in the craft save this temporary one. Later on, when the masters became capitalists of a sort, and the apprentices were, like the masters, privileged, the class of journeyman craftsman came into existence; but it does not seem that the difference between them and the aristocracy of the guild was anything more than an arbitrary one. In short, during all this period the unit of labour was an intelligent man.

Under this system of handiwork no great pressure of speed was put on a man’s work, but he was allowed to carry it through leisurely and thoughtfully; it used the whole of a man for the production of a piece of goods, and not small portions of many men; it developed the workman’s whole intelligence according to his capacity, instead of concentrating his energy on one-sided dealing with a trifling piece of work; in short, it did not submit the hand and soul of the workman to the necessities of the competitive market, but allowed them freedom for due human development.

It was this system, which had not learned the lesson that man was made for commerce, but supposed in its simplicity that commerce was made for man, which produced the art of the Middle Ages, wherein the harmonious co-operation of free intelligence was carried to the furthest point which has yet been attained, and which alone of all art can claim to be called Free.

The effect of this freedom, and the widespread or rather universal sense of beauty to which it gave birth, became obvious enough in the outburst of the expression of splendid and copious genius which marks the Italian Renaissance. Nor can it be doubted that this glorious art was the fruit of the five centuries of free popular art which preceded it, and not of the rise of commercialism which was contemporaneous with it; for the glory of the Renaissance faded out with strange rapidity as commercial competition developed, so that about the end of the seventeenth century, both in the Intellectual and the Decorative arts the commonplace or body still existed, but the romance or soul of them was gone. Step by step they had faded and sickened before the advance of commercialism, now speedily gathering force throughout civilisation. The domestic or architectural arts were becoming (or become) mere toys for the competitive market through which all material wares used by civilised men now had to pass.

Commercialism had by this time well-nigh destroyed the craft-system of labour, in which, as aforesaid, the unit of labour is a fully-instructed craftsman, and had supplanted it by what I will ask leave to call the workshop system, wherein, when complete, division of labour in handiwork is carried to the highest point possible, and the unit of manufacture is no longer a man, but a group of men, each member of which is dependent on his fellows, and is utterly useless by himself. This system of the workshop division of labour was perfected during the eighteenth century by the efforts of the manufacturing classes, stimulated by the demands of the ever-widening markets; it is still the system in some of the smaller and more domestic kinds of manufacture, holding much the same place amongst us as the remains of the craft-system did in the days when that of the workshop was still young. Under this system, as I have said, all the romance of the arts died out, but the commonplace of them flourished still; for the idea that the essential aim of manufacture is the making of goods still struggled with a newer idea which has since obtained complete victory, namely, that it is carried on for the sake of making a profit for the manufacturer on the one hand, and on the other for the employment of the working class.

This idea of commerce being an end in itself and not a means merely, being but half developed in the eighteenth century, the special period of the workshop system, some interest could still be taken in those days in the making of wares. The capitalist manufacturer of the period had some pride in turning out goods which would do him credit, as the phrase went; he was not willing wholly to sacrifice his pleasure in this kind to the imperious demands of commerce; even his workman, though no longer an artist, that is a free workman, was bound to have skill in his craft, limited though it was to the small fragment of it which he had to toil at day by day for his whole life.

But commerce went on growing, stimulated still more by the opening up of new markets, and pushed on the invention of men, till their ingenuity produced the machines which we have now got to look upon as necessities of manufacture, and which have brought about a system the very opposite to the ancient craft-system; that system was fixed and conservative of methods; there was no real difference in the method of making a piece of goods between the time of Pliny and the time of Sir Thomas More; the method of manufacture, on the contrary, in the present time, alters not merely from decade to decade, but from year to year; this fact has naturally helped the victory of this machine system, the system of the Factory, where the machine-like workmen of the workshop period are supplanted by actual machines, of which the operatives as they are now called are but a portion, and a portion gradually diminishing both in importance and numbers.

This system is still short of its full development, therefore to a certain extent the workshop system is being carried on side by side with it, but it is being speedily and steadily crushed out by it; and when the process is complete, the skilled workman will no longer exist, and his place will be filled by machines directed by a few highly trained and very intelligent experts, and tended by a multitude of people, men, women, and children, of whom neither skill nor intelligence is required.

This system, I repeat, is as near as may be the opposite of that which produced the popular art which led up to that splendid outburst of art in the days of the Italian Renaissance which even cultivated men will sometimes deign to notice now-a-days; it has therefore produced the opposite of what the old craft-system produced, the death of art and not its birth; in other words the degradation of the external surroundings of life—or simply and plainly unhappiness. Through all society spreads that curse of unhappiness: from the poor wretches, the news of whom we middle-class people are just now receiving with such naive wonder and horror: from those poor people whom nature forces to strive against hope, and to expend all the divine energy of man in competing for something less than a dog’s lodging and a dog’s food, from them up to the cultivated and refined person, well lodged, well fed, well clothed, expensively educated, but lacking all interest in life except, it may be, the cultivation of unhappiness as a fine art.

Something must be wrong then in art, or the happiness of life is sickening in the house of civilisation. What has caused the sickness? Machine-labour will you say? Well, I have seen quoted a passage from one of the ancient Sicilian poets rejoicing in the fashioning of a water-mill, and exulting in labour being set free from the toil of the hand-quern in consequence; and that surely would be a type of man’s natural hope when foreseeing the invention of labour-saving machinery as ’tis called; natural surely, since though I have said that the labour of which art can form a part should be accompanied by pleasure, no one could deny that there is some necessary labour even which is not pleasant in itself, and plenty of unnecessary labour which is merely painful. If machinery had been used for minimising such labour, the utmost ingenuity would scarcely have been wasted on it; but is that the case in any way? Look round the world, and you must agree with John Stuart Mill in his doubt whether all the machinery of modern times has lightened the daily work of one labourer.

And why have our natural hopes been so disappointed? Surely because in these latter days, in which as a matter of fact machinery has been invented, it was by no means invented with the aim of saving the pain of labour. The phrase labour-saving machinery is elliptical, and means machinery which saves the cost of labour, not the labour itself, which will be expended when saved on tending other machines. For a doctrine which, as I have said, began to be accepted under the workshop system, is now universally received, even though we are yet short of the complete development of the system of the Factory. Briefly, the doctrine is this, that the essential aim of manufacture is making a profit; that it is frivolous to consider whether the wares when made will be of more or less use to the world so long as anyone can be found to buy them at a price which, when the workman engaged in making them has received of necessaries and comforts as little as he can be got to take, will leave something over as a reward to the capitalist who has employed him. This doctrine of the sole aim of manufacture (or indeed of life) being the profit of the capitalist and the occupation of the workman, is held, I say, by almost everyone; its corollary is, that labour is necessarily unlimited, and that to attempt to limit it is not so much foolish as wicked, whatever misery may be caused to the community by the manufacture and sale of the wares made.

It is this superstition of commerce being an end in itself, of manmade for commerce, not commerce for man, of which art has sickened; not of the accidental appliances which that superstition when put in practice has brought to its aid; machines and railways and the like, which do now verily control us all, might have been controlled by us, if we had not been resolute to seek ‘profit and occupation’ at the cost of establishing for a time that corrupt and degrading anarchy which has usurped the name of Society.

It is my business here tonight and everywhere to foster your discontent with that anarchy and its visible results; for indeed I think it would be an insult to you to suppose that you are contented with the state of things as they are; contented to see all beauty vanish from our beautiful city, for instance; contented with the squalor of the black country, with the hideousness of London, the wen of all wens, as Cobbett called it; contented with the ugliness and baseness which everywhere surround the life of civilised man; contented, lastly, to be living above that unutterable and sickening misery of which a few details are once again reaching us, as if from some distant unhappy country, of which we could scarcely expect to hear, but which I tell you is the necessary foundation on which our society, our anarchy, rests.

* * * * *

Now above all things I want us not to console ourselves by averages for the fact that the riches of the rich and the comfort of the well-to-do are founded on that terrible mass of undignified, unrewarded, useless misery, concerning which we have of late been hearing a little, a very little; after all we do know that is a fact, and we can only console ourselves by hoping that we may, if we are watchful and diligent (which we very seldom are) we may greatly diminish the amount of it. I ask you is such a hope as that worthy of our boasted civilisation with its perfected creeds, its high morality, its sounding political maxims? Will you think it monstrous that some people have conceived another hope, and see before them the ideal of a society in which there should be no classes permanently degraded for the benefit of the Commonweal?

For one thing I would have you remember, that this lowest class of utter poverty lies like a gulf before the whole of the working classes, who in spite of all averages live a precarious life; the failure in the game of life which entails on a rich man an unambitious retirement, and on a well-to-do man a life of dependence and laborious shifts, drags a working man down into that hell of irredeemable degradation.

I hope there are but few at least here who can comfort their consciences by saying that the working class bring this degradation on themselves by their own unthrift and recklessness. Some do no doubt; stoic philosophers of the higher type not being much commoner among day labourers than among the well-to-do and rich; but we know very well how sorely the mass of the poor strive, practising such thrift as is in itself a degradation to man, in whose very nature it is to love mirth and pleasure, and how in spite of all that they fall into the gulf. What! are we going to deny that when we see all round us in our own class cases of men failing in life by no fault of their own? Nay, many of the failures worthier and more useful than those that succeed: as might indeed be looked for in the state of war which we call the system of unlimited competition, where the best campaigning luggage a man can carry is a hard heart and no scruples.

For indeed the fulfilment of that liberal ideal of the reform of our present system into a state of moderate class supremacy is impossible because that system is after all nothing but a continuous implacable war; the war once ended, commerce, as we now understand the word, comes to an end, and the mountains of wares which are either useless in themselves or only useful to slaves and slave-owners are no longer made, and once again art will be used to determine what things are useful and what useless to be made; since nothing should be made which does not give pleasure to the maker and the user, and that pleasure of making must produce art in the hands of the workman; so will art be used to discriminate between the waste and the usefulness of labour; whereas at present the waste of labour is, as I have said above, a matter never considered at all; so long as a man toils he is supposed to be useful, no matter what he toils at.

I tell you the very essence of competitive commerce is waste; the waste that comes of the anarchy of war. Do not be deceived by the outside appearance of order in our plutocratic society. It fares with it as it does with the older forms of war, that there is an outside look of quiet wonderful order about it; how neat and comforting the steady march of the regiment; how quiet and respectable the sergeants look; how clean the polished cannon; neat as a new pin are the storehouses of murder; the looks of adjutant and sergeant as innocent looking as may be; nay, the very orders for destruction and plunder are given with a quiet precision which seems the very token of a good conscience; this is the mask that lies before the ruined cornfield and the burning cottage, the mangled bodies, the untimely death of worthy men, the desolated home.

All this, the results of the order and sobriety which is the face which civilised soldiering turns towards us stay-at-homes, we have been told often and eloquently enough to consider; often enough we have been shown the wrong side of the glories of war, nor can we be shown it too often or too eloquently; yet I say even such a mask is worn by competitive commerce, with its respectable prim order, its talk of peace and the blessings of intercommunication of countries and the like, and all the while its whole energy, its whole organised precision is employed in one thing, the wrenching the means of living from others; while outside that everything must do as it may, whoever is the worse or the better for it; like the war of fire and steel, all other aims must be crushed out before that one object; worse than the older war in one respect at least, that whereas that was intermittent, this is continuous and unresting, and its leaders and captains are never tired of declaring that it must last as long as the world, and is the end-all and be-all of the creation of man of his home; of such the words are said:

For them alone do seethe

A thousand men in troubles wide and dark;

Half ignorant they turn an easy wheel

That sets sharp racks at work to pinch and peel.

What can overthrow this terrible organisation so strong in itself, so rooted in the self-interest, stupidity, and cowardice of strenuous narrow-minded men? So strong in itself and so much fortified against attack by the surrounding anarchy which it has bred?

Nothing, but discontent with that anarchy, and an order which in its turn will arise from it, nay, is arising from it, an order once a part of the internal organisation of that which it is doomed to destroy.

For the fuller development of industrialism from the ancient crafts through the workshop system into the system of the factory and machine, while it has taken from the workmen all pleasure in their labour or hope of distinction and excellence in it, has welded them into a great class, and has by its very oppression and compulsion of the monotony of life driven them into feeling the solidarity of their interests and the antagonism of those interests to those of the capitalist class: they are all through civilisation feeling the necessity of their rising as a class. As I have said, it is impossible for them to coalesce with the middle classes to produce the universal reign of moderate bourgeois society which some have dreamed of; because however many of them may rise out of their class, these become at once part of the middle class, owners of capital, even though it be in a small way, and exploiters of labour; and there is still left behind a lower class which in its own turn drags down to it the unsuccessful in the struggle; a process which is being accelerated in these latter days by the rapid growth of the great factories and stores which are extinguishing the remains of the small workshops served by men who may hope to become small masters, and also the smaller of the tradesmen class; thus then, feeling that it is impossible for them to rise as a class, while competition naturally, and as a necessity for its existence, keeps them down, they have begun to look to association as their natural tendency, just as competition is of the capitalists; in them the hope has arisen, if nowhere else, of finally making an end of class degradation.

* * * * *

I know there are some to whom this possibility of the getting rid of class degradation may come, not as a hope, but as a fear; these may comfort themselves by thinking that this Socialist matter is a hollow scare, in England at least; that the proletariat have no hope, and therefore will lie quiet in this country, where the rapid and nearly complete development of commercialism has crushed the power of combination out of the lower classes; where the very combinations, the Trades Unions, founded for the advancement of the working class as a class, have already become conservative and obstructive bodies, wielded by the middle-class politicians for party purposes; where the proportion of the town and manufacturing districts to the country is so great that the inhabitants, no longer recruited by the peasantry, but become townsmen bred of townsmen, are yearly deteriorating in physique; where lastly education is so backward.

It may be that in England the mass of the working classes has no hope; that it will not be hard to keep them down for a while—possibly a long while. The hope that this may be so I will say plainly is a dastard’s hope, for it is founded on the chance of their degradation. I say such an expectation is that of slaveholders or the hangers-on of slaveholders. I believe, however, that hope is growing among the working class even in England; at any rate you may be sure of one thing, that there is at least discontent. Can any of us doubt that since there is unjust suffering? Or which of us would be contented with 10s. a week to keep our households with, or to dwell in unutterable filth and have to pay the price of good lodging for it; Do you doubt that if we had any time for it amidst our struggle to live we should look into the title of those who kept us there, themselves rich and comfortable, under the pretext that it was necessary to society?

* * * * *

Remember we have but one weapon against that terrible organisation of selfishness which we attack, and that weapon is Union. Yes, and it should be obvious union which we can be conscious of as we mix with others who are hostile or indifferent to the cause; organised brotherhood is that which must break the spell of anarchical Plutocracy.

One man with an idea in his head is in danger of being considered a madman; two men with the same idea in common may be foolish, but can hardly be mad; ten men sharing an idea begin to act; a hundred draw attention as fanatics, a thousand and society begins to tremble, a hundred thousand and there is war abroad, and the cause has victories tangible and real—and why only a hundred thousand? Why not a hundred million and peace upon earth? You and me who agree together, it is we who must answer that question.

2 Replies to “Art, Labour and Socialism”