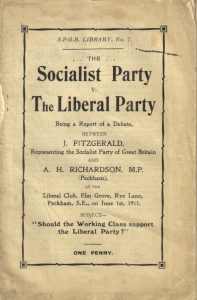

S.P.G.B. LIBRARY, No. 7.

S.P.G.B. LIBRARY, No. 7.

The Socialist Party versus The Liberal Party

Being a Report of a Debate Between J. FITZGERALD,

Representing the Socialist Party of Great Britain

And H. RICHARDSON, M.P. (Peckham)

AT THE Liberal Club, Elm Grove, Rye Lane, Peckham, S.E., on June 1st 1911

SUBJECT – “Should the Working Class support the Liberal Party?”

———————–

ONE PENNY

Should the Working Class support the Liberal Party?

A DEBATE

THE CHAIRMAN (Mr. J. E. Dobson)

Ladies and Gentlemen.

It is not my province to-night to perform my usual occupation of making speeches. That is not my business, and I, therefore, do not propose detaining you with any remarks of my own. As you know, we are here to-night for the purpose of listening to a discussion – a discussion which I personally regard as of extreme interest, and one to which I am sure you will listen with the greatest possible attention, without unduly interrupting in any way either of the speakers.

The debate is between a representative of the Socialist Party and Mr. Richardson, and as the representative originally announced for the Socialist Party has been unable to attend, it has been arranged that Mr. Fitzgerald acts as a substitute, and I understand he is equally capable. He will open the debate in a speech of not more than 45 minutes, to which Mr. Richardson will reply, and each speaker will then have another twenty minutes. The question is a very important one, and I can only say that I hope both sides will listen with every attention. I now call upon Mr. Fitzgerald to address you.

MR. FITZGERALD

Mr. Chairman and friends – In entering into this discussion I propose, first of all, to take the title of this debate and ask a question upon it. The question we have to discuss is: “Should the Working Class Support the Liberal Party?” and the first question I have to put is: Why should the working class support any political party at all? Why should they enter into politics in any shape or form? It means, so far as they are concerned, so much time wasted, unless they are to receive some benefit for the support they extend.

The second question we have to ask is: What is the Liberal Party? why does it exist? whose interests does it represent? To answer these questions it is necessary for us to go below the surface; it is necessary that we find out the reasons for the existence of this party. And having done so, we can draw our deductions as to whether it is worthy of the support of the working class.

The moment, however, you begin this examination you will see (as the title of the debate admits) that there exists another class, besides the working class; you will see that we Socialists are correct when we claim that in society there are two classes – the working class and the capitalist class – and you will further see that, in entering into political action, the various parties do so because political action embodies certain factors in operation in modern society; so that when we talk about the Liberal or the Conservative parties being supported or placed in possession of government, we mean that an examination will show that that party, by virtue of its possession of government, holds control of, and is able to manipulate, the forces by which the general affairs of society are conducted.

Let us go a little further into this. Look around you for a moment; just go into one or two details and you will then see how closely this applies to your every-day life.

You are often told that man is a social animal, that he lives a life in company, with his fellow men, and that to do this he has to submit to and obey certain rules, which are declared to be necessary for the conduct of society. If, however, you examine those rules, you will find that they are invariably issued by a section at the top, and that in very many instances they largely redound to the injury and detriment of the working class.

For instance, take the case of the man in want, the man who is destitute. Ask yourself: Why does he remain in want? Why does he continue to be destitute? Why is his suffering perpetuated? The obvious answer and the only answer is, that there exists in society certain forces, certain regulations, known under the name of “law and order,” which tell this man distinctly that, unless he is able to sell his labour-power to an employer in accordance with the recognised rules, he must remain poor and destitute; he must keep where he is; and that any attempt to escape from this condition by any other method than the “legal” one will at once be met with penalty. Consequently, the first point I want you to remember is that “law and order” are there to preserve certain relationships in the conduct of society, and that these relationships are conserved by those who control society, and who are utterly indifferent as to the injurious manner in which they operate upon the working class. There is the first force you come up against in your examination of how society is regulated, and how its affairs are conducted.

Further, most of you will have noticed that when these concrete embodiments of “law and order” – the magistrate and the policeman – are unable to effectually meet and overcome any trouble and disorder that arises, then other forces – the Army and Navy – are brought into requisition for this purpose. The object in every case is the same, viz, to quell every disturbance so that society may proceed along those lines laid down by those who control the present system, and who always control it in the interest of the class they represent. It can, therefore, be clearly seen that those who, for the time being, control the forces in which I have referred, actually and in reality control society itself, because having those powers at their command, they can and do use them for any desired purpose, and settle what action shall be taken in any given case. It is, I think, therefore obvious that the control of these forces is a very important factor for those who wish to be the ruling class in society.

As I have shown that the ruling class control the armed forces of the nation, the next point for us to consider is how are they controlled? how are they directed? If you will go over any particular instance in which these forces have been brought into action, you will see clearly not only the method or the means by which they are manipulated, but, with another step, you will also see the interest that lies behind them.

In the first place, when the military, naval, or police forces are armed in any direction, certain orders are issued for that purpose, and the soldier, sailor or policeman moves along the lines laid down for him in those directions. It is for us to consider how those lines laid down; how those orders are issued, because this is the first step in getting to the bottom of the question.

The judicial machinery moves according to rules already laid down, but the Army and Navy have to await special instructions. You have the recent instance in South Wales, where a conflict has arisen between the mine owners and the miners. When the trouble occurred, first the police and then the soldiers were sent – all for the purpose of upholding “law and order.” And if you look into the causes which resulted in the soldiery being sent there, you will find that first the local authority sends a request to the Home Office, the Home Office issues a request to the War Office, and the troops ultimately move in the direction required. You will find that the control and manipulation of these forces are carried on by the various political officers, and it is through these departments that instructions come with regard to the movement of troops in any required direction for any specific purpose. In a word, the Houses of Parliament make laws and alter them as in their wisdom they determine; they appoint the officers controlling the executive departments and they have at their disposal the means of ensuring that these laws are carried into effect for the carrying on of society to-day.

This is a very brief examination, but it will be sufficient to show that society to-day, with its rules and regulations, is shaped by those who are in possession of political power, and to sum the matter up, the possession of the means and the power of manipulating the forces I have mentioned, constitutes the essential operation of political power, and rests in the hands of Parliament. It is here the crux of the situation lies, because those holding this power are in possession of the means whereby they can dominate society. The control, therefore, of political power means the control of society.

Now turn to society itself and you will find that, broadly speaking, it is divided into two classes – the capitalist class and the working class. I am quite aware that you cannot, as it were, take a knife and cut down between the divisions clean and hard, just the same as in the animal and vegetable kingdoms it is impossible for the biologist to definitely state the line of division. But exactly as does the biologist make, on scientific lines, his division between these kingdoms, so we are able to point to the distinctive characteristics which differentiate the capitalist class from the working class.

The working class of to-day is distinguished by certain peculiarities existing in modern society, which were unknown before. Take first their character as workers. To-day, when you say a man is a working man you mean something else as well – you mean he is poor. Those terms – “poor man” and “working man” – are synonymous and interchangeable. This is language which is scientifically accurate. Now why is the working man poor? Try and analyse the causes of his poverty. Look around you and you will see in operation factors not known in any previous stage of human history. You will notice as a pre-eminent, as a striking and self-evident fact, that there is no lack of the power of producing wealth. All over the world to-day, wealth is being piled up in enormous quantities, but, co-incident with this marvellous accumulation, there remains the patent fact that the working class is still poor, still in poverty relative to the powers of wealth production. It is, of course, quite true that you had poverty in other periods of the world’s history, but in general the poverty and distress of those days were due to such things as famine, drought, internecine warfare, some failure of Nature, or the failure of man to understand Nature and adapt himself to her.

Those were the main causes of the poverty of previous eras; but to-day you have the altogether different conditions. You have operating in society, factors that were unknown before – you have the hitherto unknown phenomenon of want in the midst of plenty, and because there is plenty. This may be proved to anyone.

For instance, take a man who is out of work and try and ascertain the causes of his unemployment. He will tell you he is out of work because there is not sufficient work for everybody. Why is there not sufficient work? Go to any employer and put the question to him, and he will tell you he cannot employ men out of work because he has barely sufficient work for the men he already employs; he will tell you that he has to produce for the market – that he can only employ such a number of men as can produce those goods he is able to dispose of on the market – that he is continually meeting with difficulties in disposing of the goods he has already produced, and therefore, he cannot make use of any men in additions to those he has.

You will also learn the further fact that the productive capacity of each individual worker to-day is enormously greater than in former periods, with the result that wealth is produced in much greater quantities than the markets can immediately absorb. This applies to all industries, and the inevitable result is, that while the increased productive capacity of the worker floods the market with goods, the purchasing power of the worker does not keep pace with his productive capacity, and you therefore have, as a necessary consequence, a large army of unemployed and the miseries that always follow in the wake of unemployment.

This, as I have already said, is a phenomenon hitherto unknown. The worker suffers because he is able to produce far more than formerly. His chances of securing a living are smaller than before, and the insecurity that haunts him from the cradle to the grave, is intensified in a manner unknown to any period of human history. He has greater difficulty in getting a job and still greater difficulty in holding it. In addition, the age at which he can hope to obtain employment is continually decreasing – he is too old, not merely at 70, 60 or 40, but, as the Westminster Labour Exchange stated a little while ago, he is too old at 30.

It is a well-known fact that in a good many centres you cannot get a job if you are over 30 – this applies particularly to the chemical factories and some others – so that you as workers are faced with the facts that not only is there increased competition for the work itself, but the period in which you are allowed to work is steadily declining; and all the time there are alongside of these facts increased powers of wealth production, and an enormous increase in the actual wealth produced.

This is essentially the position of the working class. The accuracy of this statement may be tested by any man who cares to study the available facts and figures for himself. It is a statement in no way exaggerated or distorted, and I would therefore ask you: Why is it that he working class are in relative misery compared with the enormous amount of wealth that is produced?

I have already given you the answer: the employer is only concerned, while engaging you, to carry through certain operations for the purpose of placing the results of your labour on the market for sale. You know full well, all of you, that when you go into the mill or the factory to produce goods, those goods are not taken by the employer for his own personal consumption. The man who produces motor cars, whilst he may require one, or even two, for his own use, does not ride about in the whole lot produced in his workshop – they are produced primarily to sell upon the market. This applies to every article of commerce. The employer is bound, for the purposes of his business, to sell in the most favourable market he can find the goods that are produced. The sale of commodities depends, as you know, upon the demand at any given moment, and therefore, if the market demands can be met by employing, say, only two-thirds of the labour available, the remaining one-third will be out of work.

All things that are produced and exist upon the market in any shape or form, consist of two elements only. The first is the raw material provided by Nature. No man has yet discovered how to create or destroy a single atom of matter – all that is done is to change its form and place – and consequently, all wealth that exists is the result of human energy applied to nature-given material. As this is so, the question for us is: Who is it in society that applies this energy? You know who it is – the working class. They are the only ones who, as a class, apply their energy in order to change the form and position of natural material, so that we may, as the resultant, have wealth existing in the various forms it does.

The working class is the only class that does this, and yet upon the admissions of orthodox statisticians and politicians; upon the admission continually being made in your daily papers, and in the speeches of your public men, the working class, who produce all this, have as their share the poorest, the worst, and the smallest portion.

This is so obvious that it does not require the proof of figures or the admissions of eminent statesmen. Just use your intelligence; look around you, and see for yourself if those who do the work have the best of what they produce. It is admitted everywhere that they haven’t: you never see a worker riding in a magnificent motor car (except, perhaps, at election times); you never see him living in a grand house in the most fashionable quarter of the town. His share, on the contrary, is always the meanest and poorest. The best, in every sense of the word, goes to that class, with its hangers-on, who do nothing useful in the carrying on of necessary industry. And because of this method of distribution you have the spectacle everywhere confronting you, of enormous wealth in the hands of the non-producers (with all that this enormous wealth implies), and on the other hand poverty, misery, insecurity, degradation and hopeless toil as the portion of the workers. Why is it, I ask once more? How does it come about?

Suppose on Monday morning you went looking for a job either in the country or in a town. In your walk you would have noticed certain things. You would, on the one hand, see here and there stretches of vacant land, and on the other hand you would see a number of landless workers – in fact, you would be one of them. Now you know that the men out of work could, if they had sufficient tools, seed, etc., make use of the idle land for the purpose of procuring a livelihood from it. Why, therefore, do they not go on to the land? It is uncultivated, and the application of human labour to it would be beneficial to the worker. The answer is to be found in the facts of your experience, which tell you that the forces to which I have previously drawn your attention – the forces of “law and order,” exist for the purpose of preventing them going on to and making use of the land because, under the present system, it is the private property of someone else, and “property rights” are more sacred than human life.

Here you have an instance of what we mean when we say the worker is divorced from the instruments of production. You have the raw material, the land provided by Nature; but this land is not yours to use: it belongs to someone else. You cannot go on to that land except by the permission of a master, and even in the cases where you do go on, where you are employed, after having devoted your energy to the production of wealth, the wealth so produced is not yours (although your labour alone has produced it), but belongs to your master or employer.

This rule applies not merely to the land, but to all the instruments of production and to every branch of industry. If you are a factory worker; if you are engaged in machine production; if you are employed in a mill or on a railway, you know you cannot enter that factory or mill, or work on that railway, without the permission of the master, and consequently, when you are out of work you are brought face to face with this all-important fact: that the working class are without the two essential factors – the raw materials and the instruments of production. These things are owned and controlled by the master class – the capitalist class.

This being so, I would remind you of the further fact which follows from this, that when one section in society own the means of wealth production, they own the lives of those in society. As Shylock says: “He owns my life who owns the means whereby I live.”

These are matters of vast importance to you, as members of the working class. But there is a third point to which I should like to more specifically draw your attention – it is this: When you do get an opportunity of applying your energy to natural resources, the result of the application of that energy does not belong to you, but to someone else – someone who has bought you. You may engage in whatever industry you like, but whatever you produce is not yours. Up to the time of the payment of wages you have advanced to the master your labour-power upon credit, it may be for a week, a fortnight, or longer; but although your labour-power has been exercised during this period; although that which is produced is the result of your labour as a member of the working class, yet, as I have already said, and as from your experience you know, the result is not yours.

This fact is too obvious to need further detail. If you read the papers carefully you will notice that there is in them continually quoted the state of the various markets. You are told the state of the “cotton” market, the “rubber” market, the “coal” market, the “shipping” market; and you will also notice that there is regularly included the state of the “labour” market. This means that your labour-power is a commodity. It is bought and sold on the competitive market just as other things are bought and sold; and your opportunity to use this power you have is regulated by the competition on the labour-market with your fellow workers.

This is a fact which the experience of your every-day life is driving home to you with increasing conviction; and a further fact I would have you remember is that this competition is increasing because of the improvement in the powers of production, and because of this improvement, the wages you get are harder to obtain, more difficult to maintain, and easier to push down. The amount received as wages fluctuates around the cost of your subsistence, and while it may be admitted that this line is moveable, yet it is around this line that the battle is to-day being fought.

This, therefore, is your position in society as a member of the working class. You are in reality – not in imagination – owned by the master-class, by those who own and control the instruments of wealth production. The free Britisher, as well as the free and enlightened Yankee; the men who advocate Free Trade as a panacea for all the evils of our commercial system, as well as the men who propose Tariff Reform; the men who shout “freedom” and who talk about the liberty of the subject, are all in reality, if they belong to the working class, owned, controlled and dominated by those holding the political power. And as the class that holds this power is the capitalist class; it is they who own you and control the forces which dominate you.

This is the position we are endeavouring to get the working class to realise. And now I want to turn, for few moments, to the purely political field.

Anyone who looks round will not fail to observe that the parties in the political field are numerous as regards labels, but the essential question for you as workers is: Whose interests do they stand for? Whom do they in reality represent? I make the claim – which cannot be seriously disputed by anyone conversant with the history of political parties, that both the Liberal and the Tory parties, together with their hangers-on, stand no matter what they may describe themselves as, for the essentials of the present system, for the maintenance and perpetuation of capitalist domination.

The National Democratic League, with all its pretensions and claims to represent the democratic spirit, is beyond question only an appendage of the Liberal party; the Primrose League is notorious for its association with the Tory party; all the myriad crank societies advocating so-called reform in one or other of its aspects, no matter how they may differ and quarrel with each other, are agreed that at the bottom there must be conserved and preserved that system which exists to-day, and which is based on the private ownership of the means of life. That this is so can be seen by anyone who will devote a brief time to their methods, and I therefore ask, where do the working class come in? As a matter of fact they do not come in at all – in the words of the joke, they stay out. They stay out because they have not grasped the facts I have put before you, and they will continue to stay out, continue to be exploited and robbed, until they do realise they are but the slaves of the master class.

One of the ironies of the situation is this, that while the capitalist class do nothing useful in the way of wealth production, yet neither do they place themselves in possession of political power. The party that gives them this possession is the working class. The working class produce the wealth, they fill the police force, the Army and the Navy, and most wonderful irony of all, they place the means of using those forces in the hands of their enemies. They are able to do this because they have the greatest number of votes. Mr. Chiozza Money, a member of the Liberal party, has stated that out of the 7½ million voters, not less than 5¼ million are workers. This class, therefore, have already within their reach the first step toward their emancipation when they understand how to use the vote they possess. But to use this vote effectively they must understand that, not only do they already possess political power, but that they must use this power for the purpose of getting rid of the class which dominates them. They must use their power to obtain control the political machinery, so as to enter into possession of the wealth they, and they alone create, and so rid themselves of the problems of misery, poverty, degradation, insecurity, and hopeless toil which press so heavily upon them to-day.

This is the problem that faces the workers; everything else sinks into utter insignificance in comparison with it. The existence of these evils has been admitted again and again by the Liberal party. It has been admitted that a large part of the sickness of the worker is due to the poverty and misery he lives in. As he is obviously poor, he cannot be other than poorly housed and clothed, poorly fed, and subject to those diseases which are due to insufficient nourishment. Therefore the removal of these evils is the only problem that should concern those that belong to the working class. I make the statement here and now that the mass of the workers are in poverty before they have spent a penny piece of the wages they take.

The wage of the average worker, according to Government statistics, is 24s. 9d. per week, but this admittedly applies only to certain trades. The figures were only drawn up for the purposes of calculation, and some trades were left out altogether. For instance, the agricultural labourers. Had these been taken into account, with their well-known poor wages, they would have very considerably reduced this amount. It must again be remembered that these figures apply only to rates of wages, and not to actual wages received by the worker: and to show you what this means I would remind you that, during the last ten years the building trades have moved but little, and large numbers of those engaged in this industry have found themselves out of work 5 to 7 months in the year. If, therefore, the actual wage is calculated on the basis of the time the worker is in employment, and the total amount received is spread over the 52 weeks, it will show not only that the amount is considerably less than the 24s. 9d. mentioned by the Government, but how eminently true is my statement that the working class, as a whole, live in continual poverty.

Such is the position of the workers, and therefore I want to know why we should support any party at present in the field. Is the Liberal party out to emancipate you in any shape or form, seeing that they are admittedly in favour of retaining the capitalist system, from which the evils that confront you flow? The Liberal party, I might mention, contains some of the wealthiest men in the kingdom; some of the richest employers of industry; and in its long life it has never shown that in essentials it is different in degree from any other capitalist party. This fact is beyond dispute. Take, for instance, the claim of the Liberal party that they gave the working class the vote.

As a matter of fact, it was given by Disraeli in 1867, and not by the Liberal party, although they had repeatedly promised to bring in measures extending the franchise. In addition, the Liberal party has persistently persecuted the workers in the field of industry: they have continually been opposed to Trade Unions; and they have continually imprisoned their advocates. When, in 1834, the Liberal party were in power, there occurred that notorious case of the Dorchester labourers. Men were not only sentenced to transportation for claiming the most elementary rights of combination, and for daring to aspire to industrial freedom, but they were also sold into slavery under brutalising conditions.

All through their history the Liberal party have shown themselves every whit as ready to shoot the workers down as any other party have. In this respect, as in others, they are as bad as the Tories – whom they are always denouncing as the enemies of the workers. Go back to the times when they had the power; study the conditions of labour during the times when they held the reins of office. Learn how, time after time, they bitterly and ruthlessly opposed every attempt to alter, in some slight degree, the murderous conditions under which men, women and even little children, laboured in the factories, the mines, and the mills; read what they did at Mold, in Flintshire; how they supported a Tory mine-owner at Featherstone, sending soldiers to shoot down the miners; how again, they supported a Liberal shipowner at Hull, sending gunboats to overawe the men, who were asking for some slight improvement in the conditions of their labour; how they sent troops to Belfast, swarming the streets, protecting blacklegs, and shooting down inoffensive men and women in the streets; and how, in the life-time of the present Liberal Government, they have, true to their old policy of always supporting the capitalist as against the worker, sent police and troops to South Wales, and have mercilessly bâtoned little children and women.

These are but a few of the incidents in the career of Liberalism; and in the face of these and numerous other events. I ask again, why should the working class support the Liberal party? The Liberal party, as a matter of simple fact, have always been the historic enemy of the working class. They are but a wing of the capitalist class, whose interests are fundamentally opposed to the interests of the workers. From the so-called Reform Bill of 1832 to the present day, they have held political power for a longer time than the Tories; they have won election after election on the clear and definite promise, repeated by them again and again in the most solemn terms, to bring in the franchise for the worker and to improve his industrial condition. They have broken those promises as often as they have made them. The working class, whose memories have, unfortunately, been short, and who have not studied political history, have believed them when they made their election speeches; have returned them to power believing that they, and not the Tories, were the real friends of the workers. And the net result has been that every time and all the time, neither of the great parties has in the slightest degree helped them; for whatever slight improvements have been effected have been due to the combined action of the working class and to nothing else.

In the face of these facts, then, I want to know why it should be expected that the working class should help to keep this party in power, or should support them in any degree. I ask you to study the history of this party, as also of the Tory party; and when you have done that, you will learn that when you have to do is set to work to obtain control of political power for yourselves, for it is only by this method that you can hope to rid yourselves of capitalist domination and all those evils which the experience of our daily life tells us are inevitably associated with it.

(Loud Applause.)

THE CHAIRMAN

It is very gratifying to notice the attention you have given Mr. Fitzgerald, and I trust that you will kindly extend the same courtesy to Mr. Richardson, whom I now call upon to address you.

Mr. RICHARDSON

Mr. Chairman, Mr. Fitzgerald, Ladies and Gentlemen, – I want to commence by complimenting Mr. Fitzgerald upon the very powerful and extremely interesting address that he has delivered, and to which we have all listened with such attention. In commencing my reply I want to state that the cause I believe in is, to me, such a dear one; it is, in my opinion, so capable of withstanding all of the criticisms that may be levelled against it, all the objections that may be urged; it is, I believe, so capable of standing the test of rational examination, that I want to begin, not by defending Liberalism, but dealing with the essentially Socialist presentation which has been made by Mr. Fitzgerald. I hold it would be a waste of time and a want of fair criticism (and I should be the last person in the world) to pour ridicule upon the Socialists or their doctrines; because, as a student of history, I shall always remember that the greatest of all Greek philosophers, Plato, and at a later date that eminent and good Englishman, Sir Thomas More, fully subscribed to the principles, the theory, and the doctrine put before you so ably to-night by Mr. Fitzgerald. In our own time we have had such men as Robert Owen, Karl Marx, and, with a great many qualifications and modifications, John Stuart Mill, together with other eminent men who have been strong and strenuous advocates of, at least, some of the theories which Mr. Fitzgerald has entrusted to your notice; and as that is so, a system which has numbered men like those among its advocates is, at least, worthy of serious consideration.

I cannot, however, help saying at the beginning, that Socialism seems to me to be a good deal like Atheism. Right from the earliest times you have a small body of men, never considerable in number, never receiving the support of any considerable section of society, who have advocated those doctrines, and while they have been noted for earnestness and ability, while they have endeavoured to spread their views as much as they possibly could, yet over and over again their doctrines have been rejected on special grounds by the greater part of the human race.

I just wanted to say that by way of preliminary, and now we have to ask ourselves: What is the meaning of Socialism? No one denies the enormous differences between the employers and the working class – differences which cannot be defended, and which have never been successfully defended upon any ground of morality or justice. But while this is admitted, yet the point we have to consider, the question we have to ask ourselves, is: What is now the best remedy for removing the evils due to these differences? What is the best method now for improving the condition of the working class? What is going to happen if you abstain from supporting the Liberal party – the party which has been produced such fruitful legislation for the benefit for the poor of this country?

The idea of the Socialist party is, in the first place, to abolish all private ownership of property. This is a doctrine to which Socialists are logically bound to subscribe; and they claim they are going to bring it about by, in the first place, rigidly abstaining from joining any other political party – by remaining supporters of their own party and of none other. This is their doctrine and their claim, and I want to examine it closely, to see if it will stand the test of critical examination; for if it does not stand the test both of critical examination and of practical application now, then it appears to me to be of no use whatever. It may be a practical suggestion to make 2,000 years hence, but we want something now, something for 1911. We may possibly have a General Election in 1912 – which God forbid; but supposing we do have one, and suppose the Socialist applies his doctrine of abstaining from supporting any party but his own. Let all working men abstain from voting at the next General Election for the Liberal party, and what would the result be? We would either have a Government of reaction or no Government at all. Socialism would be all very well if I were speaking under the shade of trees in the Garden of Eden; but I claim that, as practical men, as men, who are faced with problems which require urgent and immediate consideration, we want something now; and I further claim that the Liberal party is the party worthy of your support because it is doing that something now. (Hear, hear!)

Let me come back to Socialism. I want to ask Mr. Fitzgerald, how we are going to apply his principles. I can quite see how we would apply them if we were going to start all over again: but how are we going to do it in 1911? You say you propose abolishing private property. How are you going to start? Are you going to declare that all private property shall cease from the 1st. January, 1912? How is your State going to deal with this property which it proposes acquiring for State purposes? There are only two possible ways by which you can get hold of the property of this country.

One is confiscation, the other compensation. That being so, are you going to take it and pay compensation or are you going to confiscate it? Just think what either of these alternatives means. I do not suppose Mr. Fitzgerald has really given the matter two minutes thought, or he would have seen the stupendous difficulties in either of these methods. I suppose that, to him, the method is unimportant, a mere matter of detail; but I would have you remember that you would be bound to apply one of them, and I want to know which one. I am indifferent what answer you make, what method you propose to adopt, because in either case I have got you. Whichever way the question is answered you are on the horns of a dilemma. If you propose compensating, then tell me where the money is to come from. You know it is an absolute impossibility to even begin to offer compensation, because the money in the kingdom is totally insufficient to pay for anything but an insignificant fraction of the wealth of the country.

Let us assume that you have passed an Act of Parliament for the purpose of taking over the private property by the method of compensation. Having passed your Act you begin to work upon it, and the first thing you take over is capital. What are the lines on which this is to be done? Let us take an instance. Take Whiteley’s – their capital is already held by some 5,000 people in shares. Are you going to issue bonds – Government bonds – on the security of Whiteley’s business? Are those bonds to bear interest? It appears to me that they must, otherwise you are not compensating the shareholders – you are simply confiscating the interest they would otherwise legitimately look for. To be anything in the nature of compensation they must bear interest; but here again, if you pay interest you are merely perpetuating, under another name, that very system you say you are out to attack. Take again railways, docks, steamship companies, big commercial concerns of all kinds, and apply the same principle to them and the moment you do so you will find that, as far as compensation is concerned, it is first of all impossible for lack of anything like sufficient money, and secondly it is absurd because, as I have already stated, the moment you agree to pay interest, that interest having to come out of the labour of the people, you would, in reality, only carry on under another name, the very system you call capitalism, and which you say you are out to destroy, so that you are destroying your own purposes.

Now let us turn to confiscation. Do you intend to proceed by this method? I frankly admit it is a much easier method if it is practicable, and it is a method with which I have no doubt Mr. Fitzgerald agrees. Let us assume you are sufficiently powerful to be able to go to the property-holders of the country and say to them: We want that property. You’ve got to give it up. Do you think they will meekly accept your dictum? – that without any opposition they will allow you to take over all the capital and all the wealth of the country. You know they will not. The moment you attempt this there will be a panic. Every man will see that his property is going to be seized, and as all men are desirous of retaining as much they can, the very thing that will happen will be that every property-holder will try and realise all he can, so that he may safely depart to where there is room for the fair play of capital and the energies and abilities of the owner. If he is in business he will sell the stock at the best price he can, and will go to America, Canada, Africa, or some other place where the Socialist party have not obtained sway, and there to live in peace undisturbed by the demands of Socialists.

Having realised all he can in cash, the next best thing will be the property on which the various businesses have been carried on. They, of course, cannot take that with them, yet the result will be that it will have no value. The next thing will be the goodwill of the business; and here I want to come to a very important point that the Socialists do not seem to be aware of, or else they treat very lightly. I want to tell you that nine-tenths of the commercial interests of this country depend upon the goodwill of its foreign trade. If you understand this you will understand that directly manufacturers break up their industries here, directly they begin to sell lock, stock and barrel. British credit is completely destroyed, the commerce of the country gone, and you have commercial chaos with all those evils that result from anything of this kind.

You may break into the Bank of England; you will find that very few bags of gold there, for the wealth of the country depends essentially upon its credit and its trade, and the moment you touch either the wealth of the country disappears. Touch capital and it disappears, it is gone for ever. This, therefore, is a matter for you to seriously consider. I hold it impossible for a Socialist to have an open mind on this, to declare, as some of them do, that they do not know how they are going to deal with this problem of taking over capital and wealth. The alternatives are there – compensation, with its impossibilities, and confiscation, with its dangers. It is a question you must face, and it is a question which, in my opinion, shows the Utopian character of Socialist proposals, because I hold that the common sense of the vast majority of the people of this country would be continually against it.

Let us pass on. Let me refer to something which I, as a member of the Liberal party, am entitled to say. I do not think for a moment that private ownership of property is in anything like a satisfactory condition. By private ownership of property I mean that system which guarantees to every man the fruits of his own industry, toil, and ability (applause); the fruits of his abstinence and application. I would say at once that, whilst I would give every man complete control over every penny he could make in his lifetime by the use of the qualities to which I have referred, yet at the same time, I would place great restrictions upon his power of bequeathing it to others who have had no part whatever in making it. I believe that the power of bequest is in conflict with the permanent and best interests of the race. This is a principle I hold, and it is a principle which the law recognises.

The law to-day is that a man cannot tie up his property for more than twenty-one years after his death. I remember an instance in which a man left a large sum of money to accumulate at compound interest. Had this been allowed to stand, the resultant sum would have been so vast that it would have given the man practically the wealth of a nation. The law, however, recognised the vicious character of this bequest and declared the will null and void, and in doing so it declared that there were national interests which could not be overridden by the interests of any man. I think the time will come when public taxation will be very largely raised by an increase in estate duties at death; for while I see no injustice in a man retaining full control during life of the property he has made, yet he should be debarred from bequeathing any amount beyond that which is necessary for the maintenance of those who are dependant upon him.

In what way does this principle, a principle of Liberal politics, differ from Socialism? We Liberals draw a line below which we will not allow persons to live without labour, yet beyond which they will have every opportunity of competing with all the strength of their manhood. We believe in competition, but Mr. Fitzgerald does not. He says capital and competition shall cease from the day the Socialist Party is returned to office. You may as well try to devise a system of gymnastics framed upon the idea that a man has no bones in his body as endeavour to frame a system which would exclude competition. Suppose that to-morrow it was announced that no class lists should be published in any schools or colleges. There would be no chance of anyone getting first or second-class honours. There would be, let us say, none of those rewards which stimulate enterprise; no sports prizes, no public distribution of rewards. What would be the result? You would immediately have indifference and neglect in all departments to which this rule was applied. And if this principle was applied to commercial life, there would be immediate stagnation. It is a matter of history that all the wealth of the world, and all those things which have been worthy of production, have been produced under the stimulus of initiative, competition and emulation.

I now come to the question which is the title of this address: Should the working man vote for the Liberal party? I should like to know where the working man would be to-day if, during the last three generations, he has not had the benefit of the legislation of the Liberal party. In the first place, he would have no right to vote at Parliamentary elections, for it was the franchise of 1832, and that of 1884, introduced and passed into law by the Liberal party, which gave him that right. He owes, therefore, his rights of political citizenship to the party to which I have the honour to belong. Then, again, to whom does he owe his education? Is that of no use? When you consider all that education means, the power of becoming acquainted with history, literature and science, the power, at least, of becoming acquainted with those things which help to make life enjoyable – good books – is this nothing? The worker is indebted to the Liberal Party for this.

The regulation of the hours of labour in the factory, mine and mill – in fact, everywhere; the introduction of more leisure into the lives of the workers – is this of no account? Here again practically the whole of this is the work of the Liberal party. Further, it is due to the Liberal party that Trade Unions are in existence. Before the Liberal party, in spite of much opposition, made them lawful, they were, in the eyes of the law, illegal conspiracies; and it was the Act of 1870, passed during a Liberal administration, which removed this disability from the shoulders of the trade unionist, and made his combinations legal.

Does not the working man owe something to the Liberal party for keeping his food untaxed? Where would he be to-day with regard to the taxation of his daily food had it not been for the Liberal party? And coming to later times, is not the record of the Liberal party something to be proud of? To whom do you owe the blessings of old-age pensions – the spending of millions in order that the aged poor may be made comfortable in the closing years of life? Is State insurance against invalidity and unemployment of no importance to the working class? These things only require mentioning to show you that the friend of the working class is in reality the party which sits on the Liberal benches in the House of Commons. Again, is not the abolition of the Veto of the Lords nothing? Just consider the cumulative effect of these measures, carried into legislation very often in the face of the most strenuous opposition, opposed by the other great party in the State, decried by the whole of the Conservative Press, but still passed; and then, if you give them fair and candid consideration, I have no doubt you will agree that the Liberal party is worthy of the support of the working class. I quite agree that there remains much yet to be done; but while I agree with this, while I hold that this will be done by the only progressive party in the State, yet I do not think any man, no matter what shade of political opinion he may be, who fairly studies the history of the Liberal party during the last eighty years, will deny that had it not been for that party, the condition of the working class would to-day be the same as it was in 1832, after nearly seventy years of unbroken Tory legislation.

On these grounds I claim that Liberalism is worthy of your support: it has been tested and has stood the test. No other party can approach it in fruitful legislation; no other party has so consistently kept in view the wishes of the working class, or so successfully endeavoured to translate into legislative enactment these wishes.

In conclusion I want to say it is not a question as to whether Socialism may or may not be left to conjecture or speculation; it is not a question as to our waiting until it has had a trial, because there is at present in Europe one country where absolutely everything Mr. Fitzgerald has advised the working class to do has been done, and with results that, in my opinion, are disastrous. I refer to Germany. No one will deny that in that country the theoretic Socialist are the only party in the State representing the working man. As a matter of fact there is no Liberal party in Germany. Broadly speaking, Germany, politically, is divided into the Tory party and the Socialist party, and bearing this in mind, let us see what has been the result. In the Reichstag the Socialist Party is exactly five times as strong as the Labour Party in the British House of Commons to-day.

What has been the result of the influence of this party upon legislature? I have no hesitation in saying that in no country in the world is legislative benefit for the working class so little felt as there. What they have been able to do in this one country, which, above all others, has a living Socialist organisation – a country which has adopted the schemes which Mr. Fitzgerald advises you to adopt (interruption) – can be clearly seen. The working man detests militarism, yet he is bound in that country to become a conscript; the working man begs for free food, and has, perforce, to eat taxed food; he begs for higher wages, and has to be content with the lower wages than men get in this country; he protests against enforced public service, but his protests are ignored; he has no liberty of public speech; he has few, if any, of the liberties enjoyed by the working class in this country.

In a word, they are miles behind us in every way, and this is what Socialism, interpreted by the Socialist party in the Reichstag, has done for them. I hope the workers of this country will profit by the example of Germany in this respect, as they have profited by the example of Germany in this respect, as they have profited by the example of Germany during the last elections so far as Tariff Reform is concerned. I would remind you that in Socialist Germany trade unions were proscribed for 22 years later than in England; that the worker is immeasurably better of here than there, and the cause of the backward condition of Germany is, I contend, directly traceable to the influence of the Socialist party there.

What is the reason, then, that we are more advanced without a Socialist party? The reason is that every man who has £100 knows that his interests are safely guarded by the Liberal party; that the channels of legitimate industry are open to him; that, provided he has energy and ability, there is every possibility of his succeeding; that there is no fear that the wealth he has acquired will be confiscated; and that in no country in the world is he safer to develop to the full the ability and talent he may be endowed with than in ours, and that nowhere has been more genuine, strenuous and successful attempts to cope with the evils of modern life than during the lifetime of the party to which I have the honour to belong.

We of the Liberal party know that there are still great things to be done. But not only do we know this, but we are attempting, in a way that no other party ever has, to deal with them. It requires statesmanship, thought, careful planning, the experience of mature years, and trust in the people; these qualities have been manifested by the great leaders of the Liberal Party. On the other hand, if the scheme propounded by the Socialists were within measurable distance of practical application; if your idea of the abolition of private property, of the destruction of initiative and healthy competition were ever likely to bear fruit, you would immediately have the whole body of Liberal opinion driven for their own protection into the camp of Tory reaction; and there would be an end to all progress, enterprise and reform. Such schemes would bring disaster, ruin, and misery upon the nation, and upon none would this calamity press so heavily as on the class Mr. Fitzgerald aspires to represent. (Loud applause.)

THE CHAIRMAN

We are getting along very nicely. I hope we shall continue in this way. I now have pleasure in calling upon Mr. Fitzgerald.

MR. FITZGERALD

Comrades and Friends, – it is impossible for me in 20 minutes to cover every point raised by my opponent. I will, however, consider those which I think most important, more particularly the one on which he again and again laid stress, and where he said, he was going to place me on the horns of a dilemma. You are going, said he, to abolish private property. How are you going to do it? Is it to be by compensation or by confiscation? It may astonish my friend when I tell him we are going to do neither.

We are going to restore property – restore it to its rightful owners. Will my opponent tell me where the owners get their property from? Will my opponent tell me where all property comes from? Is he not aware that the only wealth producers in society are the working class? This statement with which I started my address has not been disputed in any way. If it is admitted – and I challenge its denial – then the only claim to the ownership of property is having done your share in producing it. Mirabeau said there were ways of getting a living – begging, working, and stealing. The capitalist class do not work, they do not beg, so it is obvious they must steal. The only class that produce wealth are the working class, as I have just said, therefore, by endeavouring to create a system wherein the rightful owners shall hold what they produce we are simply endeavouring to restore to them that which has, obviously, by the forces in operation in society, been stolen from them. That is the answer, and you can only dispute it by proving that the capitalist class, and not the working class, create the wealth that they at present hold.

You have the raw material provided by Nature, then you have the means and instruments of wealth production produced by the working class, and you have the application of labour-power right through resulting in the myriad forms of wealth you see around you. Who produce it if the working class do not? And as the working class produce it – are, in fact, the only class engaged in the production of wealth – then they, and they alone, have a right to it, and when they enter into possession of political power, they will be able to enforce that right. To talk, therefore, about compensation or confiscation, is to assume, to unjustly assume, that the present holders of the wealth created that wealth, and that they have a right to retain it or be recompensed for it, whereas it is common knowledge that the class that hold the wealth to-day do not contribute any essential whatever towards its production. This is, and always has been, the function of the working class.

Then my opponent says: If you confiscate the wealth of the few you would have a panic – everybody would be running away after having realised on everything he could. But if everybody is running away to whom are you going to sell? You must remember that, upon my opponent’s contention, they are all running away. If, however, they all go off, there cannot be any buyers, because the class that runs away is the very class who, according to my opponent, is in a position to buy. Then again, where would they go? Where would they take that cash (it is obvious they could take little else) which each one is going to get by selling to someone else who in turn is anxious to realise?

My friend seems to forget a few essential facts. He seems to forget, first of all, that his realisation scheme is impossible; that if ever there was a dream, an absurdity, it is this. He seems to forget that the capitalists of other countries would strenuously object to the invasion of a horde of strangers whose sole object was to gain was to gain possession of the markets held by them. He also seems to forget that in any country in the world where you would care to go, wherever you have capitalism, there you have side by side with it, a Socialist movement, born inevitably out of the conditions of capitalism. All over the world there exists an ever-growing party determined to put an end to the exploitation of the worker, and to the miseries bound up with it. Why, about three years ago Marx’s great work was being translated into Chinese, so even there you have the beginnings of the study of capitalism and its horrors. Where, then, will you go to with the property you have realised – assuming that you realise anything at all? You talk about the difficulties of Socialism, the difficulties which would confront you in any attempt to escape the tide of Socialist activity are stupendous and immovable, because the phenomenon from which you would escape would meet you in every corner of the civilised world.

My opponent says he would defend the right of the individual to the result of his own labour and abstinence. I agree. So would I, but the difference between us is this: I hold that the capitalist takes the fruits of others’ labour and abstinence, and to this he does not agree.

Then we are told that under Socialism human nature would not have free play; that there would be no room for incentive or initiative or healthy competition (whatever that may mean), and that everything due to the exercise of the se qualities would tend to disappear. I would like to ask my friend what incentive is there to the vast mass of the nation under capitalism. Am I to understand that by incentive he means a cash reward? Am I to understand that men live only for monetary profit? If he means this, then, on his own showing, the working class must be debarred from initiative under the system he defends, because their opportunities of monetary reward, of improving their condition while capitalism lasts, are practically nil. Again, is there no such thing as emulation? Are there no other qualities in human nature that require expression than greed? Was Newton animated by the desire for money when he applied his energy and ability to solving the greatest problems of science, and discovered the law of gravitation? Did Darwin look for cash reward as the result of his long years of arduous study around the problem of natural selection?

Do the men eminent in the scientific world, the men engaged in exploration and dangerous research, the men and women who devote their time, and often sacrifice their lives, in the battle against despotism in all its forms – do these work for money? I am prepared to admit that in some cases the money question is already solved for them, but then, according to my friend, there would have no been no room for incentive, as there would have been nothing left for them to apply their energies to.

History teems with instances showing that, in all times, the world over, men are ready to do the best work under the best conditions. All they require is the opportunity. This, to-day, is denied to the working class; their dull, drab lives leave no room for development. Stunted and dwarfed, denied the fruits of their own labour, how can you expect them to display the qualities you refer to in any great measure? The conditions of capitalism are pre-eminently adapted to crush out all the nobler instincts of men; but in spite of this, it is a slander on the average man and woman to say that they exist and apply their faculties solely for monetary reward. You have only to look around you to find instance after instance where men and women, with no hope of reward, devote their lives, not merely to the wants of those dependant upon them, but in an endeavour to hasten the time when, by the cessation of economic exploitation, it will be possible to give full play to the faculties of the myriad men and women who are, to-day, but instruments for producing wealth for the master class.

Again, our opponent tells us that the Liberals were responsible for giving you the political power you have. We were referred to 1832 and 1884. I am surprised at the reference. As a matter of fact, the franchise of 1832 gave the middle class only the vote: its clauses were so framed as to exclude the working class. The working class did not have the vote until 1867, when it was given to a section of them by a Tory Minister, Disraeli. From 1832 to 1866, out of nine Parliaments the Liberals held office in seven or eight. They were returned to power on the promise that they would bring in the franchise for the working man, and each time they deliberately broke that promise. Your Liberal historian, Justin McCarthy, will tell you that 1832 did nothing for the worker, and 1884 was merely a question of extending the vote to the “latchkey class” – of giving the appearance of power to the working class.

Then we are informed that the Liberals passed the Factory Acts. Again I say the first Acts in this direction were passed by the Tories. The man whose name is associated pre-eminently with these measures was a Tory, Lord Shaftesbury. Time after time his measures were thrown out by the Liberal party; time after time men high in this party used every endeavour to prevent the Act becoming law. Bright, Cobden, and Gladstone were notorious in this direction. Bright and Cobden were bitterly opposed to Trade Unions, to decreasing the hours worked in a factory and mine, and to the abolition of child labour. “I would sooner be under a Dey of Algiers than under the tyranny of a trade union,” said Cobden. The famous Ten Hours Act of 1847 was denounced by Bright as one of the worst Acts ever put on the Statute Book. What was the Act of 1871 passed by the Liberals? Sidney Webb declares that it was worse than a fraud in its claim to legalise Trade Unions. It was, in reality, the Act of 1875 that did this.

We are then told about their precious old-age pensions and insurance against sickness and unemployment. The former measure was in reality introduced for the saving of rates, in fact, the Liberal party have admitted in a leaflet that there will be an annual saving of some 1½ millions, and as the working class do not pay the rates, it is obviously a measure for the benefit of the master class. What does it amount to, even assuming the master class lost by it? It means that a minimum of 1s. and a maximum of 5s. shall be paid to persons over 70 who satisfy the authorities on a number of points; it means that as no one can possibly live on 5s. a week, they must necessarily be a burden on their friends and relatives, who themselves are poor; it means, above all, a saving in workhouse expenditure, which was the main object aimed at by the producers of the measure.

And when we turn to State insurance we see that to be a fraud. Lloyd George himself admitted that so far as the working class are able to ensure they do so now, yet there are millions outside. The Bill is compulsory. You are made to pay what you cannot afford under the pretence of getting it back when you are unwell. What did Lloyd George say to the employers? “You are asked to contribute something, but you will gain in the greater efficiency of the worker.” I claim that the net result will be an increase in the army of the unemployed. I claim that you will have to pay for it all along. You will have to behave yourself more when at work because you will not get unemployment relief if you misbehave yourself. If you are discharged through misconduct (and what is misconduct is left to the employer); if you leave without justifiable reason (and again the employer is to be interpreter of what is “justifiable reason”); if you leave your work because you will not be speeded up more than you are at present: in all these cases, no mater how long you have contributed, you are debarred relief. I am leaving out of consideration the fact that you will have to be continuously employed for 26 weeks in your trade before you can claim any definite relief.

Then again, sickness insurance. You will notice the money has to be disbursed through an approved society. This society must have 10,000 members; but if it is an employers’ society the number does not matter. Further, the employers must have a quarter of the representation. These measures are simply measures in the interest of the capitalist class to smash trade unions and to prevent strikes. It is definitely stated that no money is to be paid if the worker goes on strike – this is a threat to him. It is again definitely stated that if the worker is locked out no money is to be paid to him.

Here again, a weapon has been placed in the hands of the masters for the purpose of crushing opposition. The thing reeks with hypocrisy. Why was there such unanimity in the Liberal and Tory ranks over these measures? Are these parties friends or enemies? Why was the very man, Mr. Lloyd George, who, a year or two ago, was denounced through the length and breadth of the land by the Tory party and its hacks, treated by these same men to such fulsome congratulations upon his “statesmanlike” action when this measure was introduced? Why did the entire capitalist Press, Tory and Liberal, the very next morning, blow their trumpets in admiration? I want an answer to those questions. It is suspicious. The Liberal and Tory parties are supposed to be historic enemies; they are supposed to be divided into two camps; it is a question of principle with them to always to oppose to the measures of the opposite party; and yet when a measure of this kind is introduced, they are suddenly smitten with such love for the working man that they fall over each other in their anxiety to see this Bill translated into legislation. I commend a study of these matters to the working class.

Finally, I am told that Socialism must stand the test of criticism. I claim that it has stood that test all along. Professor after professor has wrecked his reputation in an endeavour to establish the unsoundness of Socialist economics. They have each come forward with a flourish of trumpets and retired discomfited. The Marxian standpoint has stood the test of every kind of criticism that can be possibly be levelled against it. The essentials of Socialism have never been successfully criticised, and these essentials are that “The working class produce all the wealth and should own and control it.” That doctrine is impregnable.

We therefore urge you to join yourselves together to obtain control of political power, so as to enter into possession of what you yourselves produce, and thus put an end to the domination of capitalism.

THE CHAIRMAN

I will now call upon Mr. Richardson for his closing speech.

MR. RICHARDSON

I am not going to avail myself of my full time. Mr. Fitzgerald has told us we are slaves. Well, all I have to say is that if we are slaves we are a jolly lot. I never saw slaves who wore their fetters so lightly.

I have gathered one valuable admission from him; I compared him to Plato, but in doing so I did not think for one moment that he would put forward such crude criticism as he has. He is going to tell people that all they have to do is to divide up, and then everyone will be happy. This is criticism of the crudest form, and I do not think it will appeal to a single man in the audience.

I am not certain whether I enjoyed more his scheme of the redistribution of wealth or his travesty of history. I have never before heard a gentleman get up and say what he has said. I have in my time followed the Fabian Society closely; I have studied their literature, made myself acquainted with their objects, and I do not think they would dream of accepting Mr. Fitzgerald as a disciple.

Let us go over part of his scheme. It appears to me that he wants to build a house before he has secured even sufficient material for the walls. Just listen to this. My argument was that if any man’s property was put in jeopardy, then, so long as it remained his property he would endeavour to realise. He retorts that the man could not go anywhere; that every country is adopting the scheme he advocates. The reply to this is obvious: so long as you leave one spot where capital may be privately owned, away goes your scheme, because the owner of property goes there as soon as he possibly can after realising on his property.

My reference to foreign trade was not touched upon. My statements regarding Germany were not dealt with. All we have is an attack upon the Liberal party – an attack which appears to consider the Liberal party the enemy of the working class. The legislation of recent years which, beyond question, has brought comfort and hope into thousands of homes, soothing the declining years of the aged, guarding the invalid and the out-of-work against the evils which have hitherto followed these – all this is nothing to my opponent. It has satisfied the working class but it has not satisfied Mr. Fitzgerald, and it appears that nothing the Liberal party might do would satisfy him. Why does he not call his doctrine what it really is? It is not a criticism of society based on rational examination, followed by constructive measures for the benefit of society – it is Anarchy.

In conclusion I want to say that, in spite of Mr. Fitzgerald’s eloquence, I will sit on the Liberal benches in the House of Commons because I hold firmly that only from there will ever proceed legislation likely to benefit the working classes. I claim that the Liberal party has proved its worth. I believe that if that fair Utopia which cheers the hearts of the great mass of the needy is ever attained, it will only be by the Liberal party through on extension of those principles which have been applied with such success during the last few years.

I do not think Mr. Fitzgerald will help his scheme by denouncing Mr. Lloyd George as an imposter. I happen to know Mr. Lloyd George, and I say without fear of contradiction, that there is no more honest and fearless worker in the cause of beneficial legislation, in the cause of the workers of this country, of everything that would make life noble and enjoyable, than Mr. Lloyd George.

I have enjoyed this discussion very much: it has been very interesting, and I have gained much insight into the manner in which the Socialists look at things. I have listened to Mr. Fitzgerald with every attention; I have carefully weighed everything he has said, and after it all I still hope and believe that no man who entered this room a Liberal will leave it a Socialist.

________________________________

The usual vote of thanks was extended to the chairman, and the meeting terminated.

_______________________________________

(From original pamphlet)

READ

The Socialist Standard

The Organ of THE SOCIALIST PARTY

THE ONLY PAPER IN THIS COUNTRY DEVOTED TO SOCIALIST PROPAGANDA.

_______________________________________

MONTHLY ONE PENNY

________________________________________

Printed by A. Jacomb. Globe Press, Stratford, E., and published by The Socialist Party of Great Britain, 10, Sandland Street, Bedford Row, London, W.C.