Proper Gander – Crossing the line

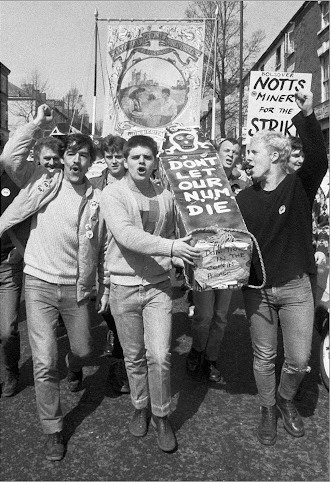

Recent strikes by teachers, drivers, lawyers, medics and others have been a reminder that this kind of organised action is one of the few ways workers have to defend our position in capitalism. This latest wave of strike action, however effective in the short-term, hasn’t managed to resonate across wider society as much as the mid-80s miners’ strike did for the previous generation. To mark the 40th anniversary of this flashpoint, Channel 4 broadcast the documentary series Miners’ Strike 1984: The Battle For Britain. Without a spoken commentary and with sparse on-screen text to set the scene, the story is told by archive footage and new interviews with miners, police and solicitors, still affected by what happened, particularly at Orgreave.

In March 1984, the National Coal Board announced the closure of 20 collieries with an expected loss of 20,000 jobs. This triggered miners to strike in Yorkshire and Scotland, supported by the National Union of Mineworkers, then led by Arthur Scargill. The NUM called for action in all areas but didn’t hold a nationwide ballot, so regional branches instead voted on whether their members would withhold their labour. The strikes lasted almost a year, in which time communities changed forever, the violent nature of the state was exposed again and the NUM ended up weakened. These three aspects of the strike were covered in each episode of the documentary.

In March 1984, the National Coal Board announced the closure of 20 collieries with an expected loss of 20,000 jobs. This triggered miners to strike in Yorkshire and Scotland, supported by the National Union of Mineworkers, then led by Arthur Scargill. The NUM called for action in all areas but didn’t hold a nationwide ballot, so regional branches instead voted on whether their members would withhold their labour. The strikes lasted almost a year, in which time communities changed forever, the violent nature of the state was exposed again and the NUM ended up weakened. These three aspects of the strike were covered in each episode of the documentary.

As described in the first part, communities such as Shirebrook in Derbyshire had built up over the decades around their local mines. As well as being the main employer in many towns and villages, a colliery would also run sports clubs and social events for employees’ families. So, when miners went on strike, they did so not just with the aim of defending their jobs, but also their communities. Unfortunately, these were damaged not just by the fight between the miners and the capitalist class’s representatives, but also that between miners who went on strike and those who continued to work. To shouts of ‘scab’, strike-breakers were driven to work on buses with grilles over the windows, guarded by police. The programme is quite sympathetic to the strike-breakers, emphasising the view that they continued to work because they were following the majority decision from ballots of local workers which were overturned by the NUM without a national vote. This, along with Scargill’s often-inflexible leadership style, raises questions about how democracy was managed in the union. Would it have been stronger if it had been more democratic?

The second episode focuses on how the state weaponised the police and courts against the strikers. The battle at Orgreave in South Yorkshire on 18 June 1984 was between strikers and lines of police equipped with truncheons, shields, crash helmets and horses. Footage recorded by the NUM and even the police shows the brutality of those in uniform. An interview with one of the officers saying they ‘never aimed for the head’ cuts to video of a dazed picketer with a bleeding head injury. Biased news reports at the time portrayed the miners as aggressors. Solicitor Gareth Peirce says it was ‘not accidental’ that police drove people away from the field where the confrontation began to the village, as doing this moved events to where others could be affected. This meant that those arrested could be charged under legislation applicable to ‘riots’, one of the criteria for which is that other people are frightened. Being found guilty of rioting could result in life imprisonment, whereas convictions for ‘unlawful assembly’ carried less harsh punishments.

Another method used by the police is described by one of the officers at Orgreave interviewed for the documentary. He says he found it ‘really bizarre’ when a senior detective dictated what he and his colleagues would write in their statements about what happened. Defence barrister Marguerite Russell says that there was ‘mass corruption’ in how the witness statements were recorded. However, all 55 miners at Orgreave charged with offences were found not guilty. One of those, Arthur Critchlow, tells us that how the charges were framed had a longer effect than the beatings. No police have faced disciplinary action for their conduct. Then-Chief Constable Tony Leonard tells us that the police were there to ‘protect’ people’s right to work as well as people’s right to picket. His words echoed those of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher who also said she would ‘never negotiate with people who use violence to achieve their objective’ even when the police had used violence to achieve her objective. The battle of Orgreave and its aftermath demonstrate how the capitalist class uses parts of the state to protect its interests and keep workers subdued, although the documentary doesn’t explain it that way.

The third episode turns to other approaches used to oppose the strikers. We’re told that a pivotal character was David Hart, one of Thatcher’s advisers who was a ‘self-promoting Scarlet Pimpernel kind of figure’, according to then-Private Secretary Andrew Turnbull. Hart’s strategy involved the National Working Miners Committee, which had been formed with the aim of ending the strike by taking legal action against the NUM. Hart brought funds to the NWMC, including contributions from capitalists such as John Paul Getty, enabling it to afford renowned lawyers. They won in court when the strike was ruled illegal as it hadn’t been decided by a nationwide ballot. After Scargill refused to halt the strike, the High Court ordered that the NUM’s assets be sequestrated, and he was further knocked when links between the union and dodgy Libyan leader Gaddafi were reported. The strike was called off in March 1985. Thatcher, who Turnbull says didn’t want to risk her reputation being harmed by the unions, had won.

The series doesn’t present a comprehensive account of the strike, as there are only brief mentions of the National Coal Board, and none at all of the Trades Union Congress or the impact of cheaper coal imports from Poland. What the programme reveals about the tactics of the state are useful, but by dwelling on the motives and actions of figures like David Hart, Arthur Scargill and Thatcher, it doesn’t reach far enough to examine the strike’s wider economic context. There’s only a rushed outline at the end about how coal had become less profitable than the emerging financial services symbolised by the up-and-coming yuppies. Another episode to explore the strike’s place in the history of capitalism would have been welcome, but wouldn’t have been commissioned.

MIKE FOSTER

Next article: Book reviews – Dyer, Headicar, Mau / The Communist review ➤