Pathfinders – Patent nonsense

Suppose that, under capitalism’s property laws, you could patent the human genome. Then, in theory, you would own the ‘rights’ to 8 billion people and their descendants, in perpetuity.

You can’t, of course, but not because people haven’t tried. Almost as soon as the DNA double helix was discovered, its co-discoverer James Watson was asked if he intended to patent it (tinyurl.com/2n6a2vrp).

He thought the idea ridiculous, but was largely alone in that opinion, as every half-baked geneticist that followed saw it as a gold rush and filed patents left, right and centre. Watson, for all his dodgy views on other matters, was convinced this technology ought to be available for the common welfare, and fought the claim-stakers, including through the courts. He couldn’t stop the rush though, and about 20 percent of the human genome, around 6,000 genes, were indeed patented. But then, in 2013 the US Supreme Court made a landmark ruling that human DNA could not be patented as it is a ‘product of nature’, which is to say, a thing which human labour has not appreciably changed or modified. This is, by the way, in line with what socialists say about human labour being the only real source of value. If it’s had no human labour usefully expended on it, you can’t patent it.

Fast forward to the MRSA antibiotic crisis, which caused over a million deaths worldwide in 2019, more than malaria or AIDS (tinyurl.com/yuasm6zw ), and could even lead to a resurgence of plague (tinyurl.com/2ucn7etk).

Antibiotics were such a wonder drug when they were first used in the 1940s that they came to be gobbled up like smarties for just about everything, including as a disease prophylactic in meat, bird and fish farming, and with scant regard for the tendency of bacteria to fight back in a ceaseless evolutionary arms race. Common interest, in a socialist society of democratic common ownership, would very likely have raised the alarm early on, but for the atomised actors of capitalism, this was another tragedy of the commons scenario. But the folly doesn’t end there – capitalism’s patent system, which defenders say drives innovation, actually prevented crucial innovation, in not one but two ways.

Firstly, the flip side of patents is that when they expire, anyone can use the technology, or copy it, for free, making the patent worthless to the holder. Since most antibiotic patents were taken out in the 1940s, they have now expired, so the big pharma companies – the ones with all the R&D cash – see no prospect of further profit and have abandoned antibiotic research, just when we need them to step up the gears.

At the risk of labouring the obvious, drug companies are not in business to cure people, but to make profits, exactly like the arms industry, the car industry, in fact any industry. If they can make more money out of hair restorer and slimming drugs, that’s what they’ll invest in. Capitalist logic is what it is, even if it kills us all, which is why we advocate a socialist system of production for needs instead.

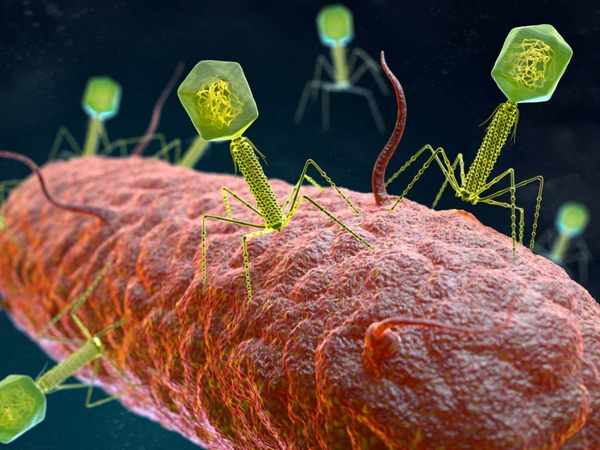

Secondly, antibiotics aren’t the only way to treat bacterial infections. You could use bacteriophages – viruses that ‘eat’ bacteria – to target and destroy the offending bacterium. Phages are very specific so you’d need the right one, culled from a huge database. This makes them harder to use than broad-spectrum antibiotics, but the advantage of phages is that they evolve, right along with the bacterium they target, meaning the bacterium can never develop permanent resistance.

Secondly, antibiotics aren’t the only way to treat bacterial infections. You could use bacteriophages – viruses that ‘eat’ bacteria – to target and destroy the offending bacterium. Phages are very specific so you’d need the right one, culled from a huge database. This makes them harder to use than broad-spectrum antibiotics, but the advantage of phages is that they evolve, right along with the bacterium they target, meaning the bacterium can never develop permanent resistance.

Phages are proven and effective, and have been used for a century at the Eliava Institute in Tbilisi, Georgia. The Institute has been treating patients with phage therapies since the 1920s, and is so successful that people fly in from all around the world to get treatment for bacterial illnesses their own doctors have pronounced incurable (tinyurl.com/m28sfm6e ).

So, given this, have phages been enthusiastically seized upon in the West, as the technology that can rescue us from the MRSA crisis? Er, no. But surely the west is planning to use them, and scale up mass phage production? Again, no. Well, there must at least be a million phage studies currently underway by western universities and drug companies? Actually, there are almost none.

WTF?

You see, here’s the rub. Phages are a ‘product of nature’, which means… you guessed it. They can’t be patented, and therefore, there is no potential profit.

Currently, some western biotech companies are working on ways to get round this restriction, using CRISPR gene-editing to tweak phages just enough to be able to claim that they are a human artefact and therefore patentable. If the tweak does something useful that’s lovely, but beside the point. The problem with this workaround is that you can’t be sure what effect the tweak is going to have, so there will be all kinds of clinical trials and regulatory hurdles to negotiate. But not to worry, capitalist regulators are not as independent as they pretend. Bodies such as the UK’s NICE and America’s FDA are subject to a degree of ‘regulatory capture’ by drug companies, who finance the bodies via required registration fees, and also promise cushy industry jobs tomorrow on the understanding that regulators play ball today (tinyurl.com/537m35am). So tweaked phages might end up being approved by fair means or foul.

Meanwhile it’s not entirely game over for antibiotics. A new class of synthetic antibiotics is able to combat drug-resistant bacteria by targeting several key proteins at once, meaning that the bacterium would have to evolve a defence against all points of attack simultaneously, a highly unlikely feat (tinyurl.com/4evjaryr). Good news, for those who can afford it.

The take-home from all this is that, in the ongoing war on MRSA, insofar as capitalism gets it right, it’s doing exactly what socialism would do. But, unlike socialism, it is critically hampered by its own profit-chasing logic, first in solving problems, and second, in not preventing them from arising in the first place.

PJS