The economics of AI

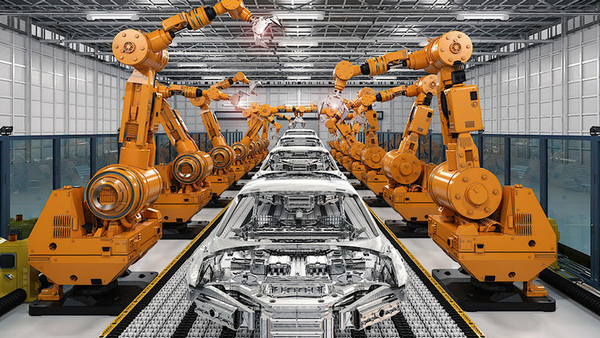

AI involves the use of machines to take, on their own, a continuing series of certain ‘intelligent’ decisions currently made by humans but in principle is no different from the use of other machines in production. AI is a further extension of the continual mechanisation that has been going on since capitalism started. Competition drives capitalist firms to mechanise in order to reduce their cost of production and stay in the battle of competition for profits. The same economic laws that govern the introduction of machinery under capitalism apply to the application of AI.

AI involves the use of machines to take, on their own, a continuing series of certain ‘intelligent’ decisions currently made by humans but in principle is no different from the use of other machines in production. AI is a further extension of the continual mechanisation that has been going on since capitalism started. Competition drives capitalist firms to mechanise in order to reduce their cost of production and stay in the battle of competition for profits. The same economic laws that govern the introduction of machinery under capitalism apply to the application of AI.

These economic laws are not what they might at first be assumed to be – that machines are introduced to reduce the amount of past and present human labour involved in producing something. This is because under capitalism there is a difference between the total amount of human labour required from start to finish to produce something and what it costs a capitalist firm to have it produced.

The total labour required to produce an item of wealth is not just that expended in the last stage of its production, as in the factory from which it emerges as a finished product, but also that expended on the production of the materials re-worked, the energy consumed and the wear and tear of the machines and buildings.

Only the labour expended at the last stage adds new labour and value. Under capitalism this is divided into wages (corresponding to the labour embodied in the workers’ labour-power) and unpaid surplus labour (the source of profit). The past labour embodied in the materials, energy, machines and buildings is transferred to the product without increasing. In the case of machines this is transferred gradually in the form of wear and tear (depreciation) until they need to be replaced. So while machines transfer value to the product it is their own pre-existing value. They do not add any new value and so do not produce surplus value; it is only the labour of those who use them that does.

Productivity can be said to increase when less labour (past and present) is required to produce an item of wealth. A machine only increases productivity to the extent that it displaces more labour than needed to produce it. Unless it does this there is no point, as far as increasing productivity is concerned, in installing it.

Under capitalism there is another limit. Machines are only installed to the extent that they replace the paid part of newly-added labour. This places the bar higher than it would be in a society, such as socialism will be, where there was no division of newly-added labour into paid and unpaid parts. It means that machines that could be installed are not, because it is not profitable to do so even though they would increase productivity.

What is relevant for a capitalist firm when considering whether to mechanise some work is the level of wages, the price of labour-power, compared to the price of the machine. The lower the wages the less the incentive to install machinery but wages can vary from place to place and from industry to industry. Marx, writing in the 1860s, gave some interesting historical examples:

‘Hence the invention nowadays in England of machines that are employed only in North America; just as in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries machines were invented in Germany for use exclusively in Holland, and just as many French inventions of the eighteenth century were exploited only in England… The Yankees have invented a stone-breaking machine. The English do not make use of it because the “wretch” who does this work gets paid for such a small portion of his labour that machinery would increase the cost of production to the capitalist’ (Capital, Vol 1, chapter 15, section 2. Penguin translation).

The same considerations apply to AI machines. AI will only be applied under capitalism when and where it will displace more paid labour than its machines cost, not when it will reduce the total amount of labour expended. Together with the high cost of producing AI machines, this will slow down and limit the extent to which AI will be applied under capitalism. In industries and countries where the labour-power to be replaced is relatively cheaper it won’t be applied at all.

Futurologists who see a more or less rapid spread of AI fail to take this into account. As do those who, following their lead, think that AI will quickly lead to mass unemployment and so to a drastic fall in paying demand which they propose to remedy by paying everyone a ‘universal basic income’. To compensate for the fall in paying demand this payment, financed out of profits, would have to be at a level that would be incompatible with capitalism. Any lesser amount would have the perverse result of reducing money wages.

The idea of the whole working class being replaced by intelligent robots is also a fantasy. AI equipment, like all machines, does not create any new value (transfer any new labour to the product) and so no surplus value; it just transfers gradually the labour expended from start to finish to make it. If production were fully automated, no surplus value would be produced, so there would be no profits and capitalism would no longer exist. Not that there is any chance of capitalism evolving into a ‘fully automated’ economy. This could only come into being if, at some point in the future after the abolition of capitalism, socialist society were to decide to go down that route (not an evident decision) and establish ‘fully automated luxury communism’. At the present time, given the low level of productivity compared to what it would need to be for that, this is science fiction. Humans are still going to have to have a substantial direct input into production for a long time to come, even after socialism has been established,

A ‘lights-out’ sector of the capitalist economy is another matter. A factory requiring no input of living human labour is not inconceivable, and a few are indeed operational. Although no surplus value would be produced in it, the capital invested there would make a profit due to the averaging of the rate of profit. This is brought about by capitals competing to invest in the most profitable sectors, with the result that all capitals, irrespective of their composition (into past and present labour), tend to get the same rate of return. The source of the profit of a lights-out factory would be a share of the surplus value created in the rest of the capitalist economy.

Given capitalism, AI will only be introduced gradually as it becomes profitable (replaces more paid labour than its own considerable cost) and much slower than would be technologically possible to increase productivity. The robots are not going to take over any time soon.

ADAM BUICK

Next article: Stuart Russell’s 2021 Reith Lectures on ‘Living with Artificial Intelligence’ ⮞