Hexham’s lesson for today

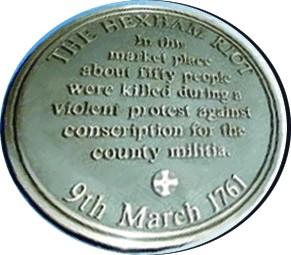

Bloody Monday! Not a Sunday night expostulation over the prospect of another working week, but a reference to 9 March, 1761. Two hundred and sixty years ago 50 or so men and women were killed and over 300 wounded in the market square in Hexham, Northumberland.

Ask most people for an example of Crown (state) brutality in the period of the burgeoning industrial revolution and they will cite St. Peter’s Fields, Peterloo, in Manchester, that quite rightly was written into the annals of infamy. However, it was not the first, nor the last, confrontation between the authorities and working people.

The specific issue in the 1760s was a form of conscription known as balloting. This had nothing to do with elections and certainly not democracy. The Militia Act had been passed through parliament to boost the said military force to free up and support the army heavily engaged in the Seven Years War (1754-63).

Potential militia recruits were to be identified and those whose names were then drawn from this census had, by law, to serve. The North East of England was nominated as the first area in which to begin this process, with Hexham one of the main centres.

9 March, 1761 was to be the initial enlistment day and rumblings of discontent had been gathering force throughout the preceding weeks. Conscious that opposition might be rather more than just grumbling, local magistrates brought a detachment of the North Yorkshire Militia into Hexham and deployed them in front of the Moot Hall.

Before them protesters gathered in huge numbers in the market square, drawing widespread support from many local parishes as well as the town itself. It was at this point that the gathering officially became a riot.

This is not to say an actual riot with violence towards persons or property was taking place, although the crowd was undoubtedly vociferous and menacing. The magistrates read The Riot Act, which instructed the crowd to disperse by law.

The assembled did no such thing and thus, officially, became rioters. They did nothing to dispel this notion, instead they advanced, many bearing staves, on the bayonets protecting the Moot Hall. In that febrile atmosphere, two militia men were shot with their own weapons. The magistrates panicked and gave the order to fire.

When the gunpowder smoke cleared, so had the market square, leaving the dead and seriously wounded. Reports at the time noted that many of the militia men were visibly shocked by the consequences. This did not prevent the authorities seeking out and arresting many of those who got away on the day.

260 years later there are still lessons to be drawn from events such as this one. Those who advocate the necessity for the violent overthrow of the capitalist state would do well to reflect on such incidents. If a crowd superior in numbers can be dealt such a dreadful blow with muskets, how much worse with modern automatic weapons.

Flying police squads

The deployment of a militia force from a different region was, in principle, utilised during the miners’ strike (1984-5) when police were brought from non-mining areas into the coalfields. The state has long since recognised the greater efficiency of its coercive powers when applied via forces deficient in local sympathies.

The deployment of a militia force from a different region was, in principle, utilised during the miners’ strike (1984-5) when police were brought from non-mining areas into the coalfields. The state has long since recognised the greater efficiency of its coercive powers when applied via forces deficient in local sympathies.

It also a dramatic confirmation of the importance of democracy, however imperfect it may be under capitalism. The Hexham ‘rioters’ had no means by which to pursue their grievance or exercise choice. Confrontation would have seemed their only option as they could not challenge, or change, the law used against them.

Collective expressions of outrage, such as that gathering in Hexham, are essentially reactive, an expression of weakness. The best that could have been hoped for was a return to the status quo. A forced repeal of The Militia Act might have inconvenienced the Crown in the short term, but was no real threat to its actual authority.

Had the ballot system been stopped at that point, life for those assembled would have simply gone back to the way things were. There would have been no forward movement, politically, economically or socially. This is the way with all immediate, pragmatic demands, even when initially met.

The state, to this day, continues to enact and employ laws to the advantage of capitalism against the interests of the vast majority, the working class. But only for as long as the working class chooses to tolerate this state of affairs. It is within the means of the working class to not only challenge, but take control of the state away from the capitalist class.

There is a danger to the state of over-reacting; the seeming solution to a local problem can become a national, and persisting difficulty if a general perception of unfair or brutal treatment develops. For all the repressive apparatus available, the Warsaw Pact states, and eventually the Soviet Union itself, could not assuage popular discontent.

It is also the case that it’s not enough to secure what turns out to be a Pyrrhic victory when the result is a case of ‘the state is dead, long live the state’. The bureaucrats become oligarchs and capitalism continues along its (not so) merry way.

What history shows

There are those of a radical bent who might argue the tragic outcome in Hexham is a demonstration of the need for a disciplined body to covertly organise rebellion. However, history does not hold much promise for such a notion.

Nearly sixty years after the Hexham ‘riot’, one year after Peterloo, such a clandestine operation occurred in the West Riding of Yorkshire. There had been a number of radical working men’s clubs established in the West Riding and Lancashire, some of their leading lights being ex-Luddites. Many a plan was drawn up with Huddersfield being an initial target for insurrectionists.

Barnsley’s Union Society was one such club with around 600 members. The Society received word that an assault on Huddersfield was scheduled for 12 April. The plan was for Barnsley men to go and join a bigger assembly at the village of Grange Moor, close by Huddersfield.

Through the night of the 11-12th approximately 400 men from Barnsley marched to a beating drum with banners bearing political slogans and carrying pikes and guns. At Grange Moor they met not with the expected thousands from across the Riding and Lancashire, but 20 or so radicals from Huddersfield. Aware of a military presence in the town, panic ensued resulting in a disorderly dispersal and the abandonment of weapons and banners. Seventeen were eventually arrested.

Years later Chartists who were sympathetic to the idea of physical force had their ardour cooled by General Napier’s invitation to some of their leaders to witness a display of cannon fire. The romance of violent revolution soon gives way faced with the grim realities of actual combat.

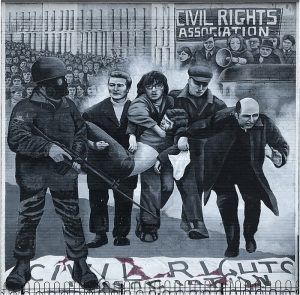

The British state has learned these lessons over two hundred years and more. If there is an instance of over-reaction, Bloody Sunday for example, first allow time to pass. Then set up a public enquiry, hold some official of the time responsible – all the better if he has died in the meantime or can resign from some prestigious post – and even offer an apology, possibly with compensation, but not too much.

Appearances are thus maintained, while the dead and injured slip away into the history books, the rule of law preserved. The state protects itself to protect capitalism and will continue to do so until the working class decides otherwise.

There was one positive factor to be found in the immediate aftermath of the Hexham debacle – the reports that the militia troops were shocked by the results of their actions. Socialists know that military men and, these days, women may be trained to kill, but are not inured to the results, as so many cases of PTSD indicate.

Also, despite being the coercive arm of the state they are workers, from working-class families. When the working class collectively decide they will democratically replace capitalism with socialism, soldiers are not going to be unaffected.

As the Hexham magistrates knew, they couldn’t rely on the local militia to confront their own neighbours so had to bring in others from elsewhere. When the socialist movement becomes worldwide, as it must to achieve socialism, there won’t be an elsewhere to draw soldiers from.

DAVE ALTON