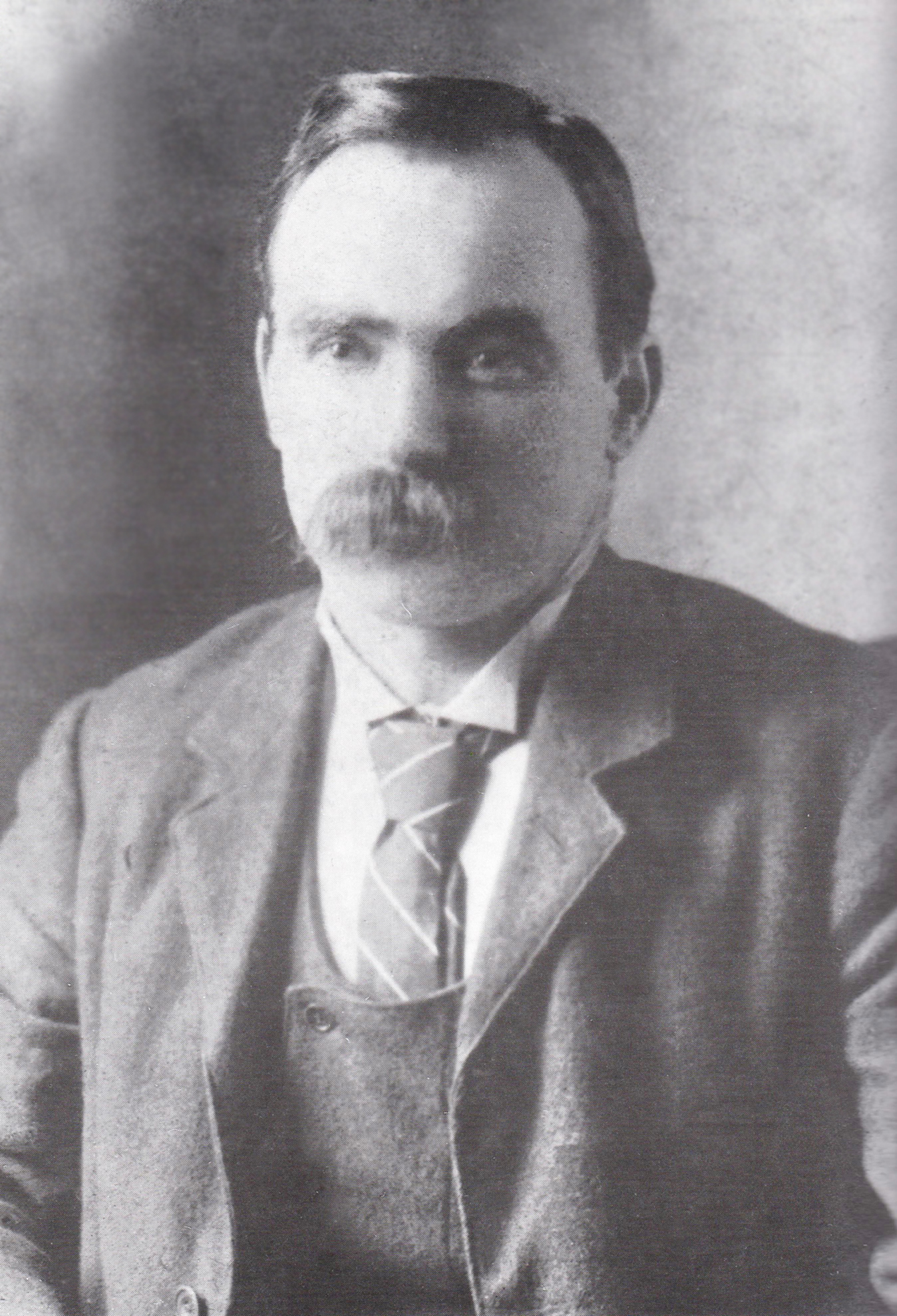

Did James Connolly Betray Socialism?

For many on the Left, James Connolly is their archetypal class warrior but his participation in the ‘Easter Rising’ was a futile heroism, utterly mistaken in tactics and objectives. What happened after showed the fallacy that priority should be given to achieving national independence first and then only afterwards turning attention towards establishing socialism.

History has confirmed that, when that happens, socialism is subsequently forgotten. We only need to look back at the fate of the Irish workers movement. A large section of it was destroyed and into the vacuum stepped opportunists ready to lavish praise upon Connolly in order to contain the class struggle. It was made all the more easy because Connolly had not fought in 1916 for workers’ demands on the question of hours of work, of wages, of factory conditions, and of the ownership of the land and industry but for a purely nationalist proclamation. The Irish Citizens Army, formed to defend workers from the police at the service of the Nationalist employer Murphy during the Dublin lock-out of 1913, ended up fading from history by dissolving itself into the ranks of the pro-employer Dublin brigade of the IRA.

No working class unity

Despite the sacrifice of lives, the Irish working class did not emerge any the stronger from the Easter Rising. Irish nationalism has always been hostile to the workers’ cause. There have been 29 general elections to the Dáil, Ireland’s parliament, since independence and Ireland’s Labour Party have won precisely none. When workers’ interests go up against nationalism in a country where politics is all about the nation, then Labour stands little chance.

In the aftermath of the First World War, Ireland saw the Limerick ‘soviet’ in the south and, in the north, the Belfast strike for a 40-hour week where, to the dismay of the Orange Lodge, ‘Bolsheviks and Sinn Feiners’ were leading astray many ‘good loyalist protestants’ and where the composition of the strike committee was a majority of Protestants, but the chairman was a Catholic. Sectarianism was being challenged. Working class militancy had arrived at Shankill Road and Sandy Row. The National Union of Railwaymen in a resolution at a conference in Belfast stated:

‘Without complete unity amongst the working classes, (we should not allow either religious or political differences to prevent their emancipation) which can be achieved through a great international brotherhood the world over, no satisfactory progress could be made.’

However, the vision of a united movement of Catholic and Protestant workers, North and South, did not become a reality and, instead of trade unionists trying to promote working class unity and solidarity, Irish workers got nationalists declaring the nation must come first; pressing their own interests the workers were said to be endangering the unity of the republican forces. The workers movement and working-class unity were the real victims of the 1916 Dublin Rising which sanctified subordinating their class interests to the nationalist interests of their capitalist employers.

Not socialist

The Rising was not socialist by any stretch of the imagination and the legacy of Connolly’s involvement has been to associate ‘socialism’ with Irish nationalism, and that has been most damaging to the cause of ‘socialism’. He did a disservice by allying a sizeable section of the workers movement to a nationalist insurrectionary project. Sean O’Casey described the Irish Volunteers, which had been set up by the Irish Home Rulers as ‘streaked with employers who had openly tried to starve the women and children of the workers, followed meekly by scabs and blacklegs from the lower elements among the workers themselves, and many of them saw in this agitation a plumrose path to good jobs, now held in Ireland by the younger sons of the English well-to-do.’

The Citizen Army’s first recruitment handbill contained a list of reasons not to join the Irish Volunteers (‘controlled by forces opposed to labour, officials having locked out union men …’) As late as January 1916 Connolly had stated: ‘The labour movement is like no other movement. Its strength lies in being like no other movement. It is never so strong as when it stands alone.’

In 1897 Connolly had written, ‘No revolutionist can safely invite the cooperation of men or classes whose ideals are not theirs and whom, therefore, they may be compelled to fight at some future critical stage of the journey to freedom,’ (which is perhaps why he is said to have later suggested ‘In the event of victory hold on to your rifles, as those with whom we are fighting may stop before our goal is reached.’) And when, at the turn of the century, the French Social Democrat leader, Millerand, accepted a position in the French cabinet, Connolly denounced this betrayal, on the basis that a workers’ party should ‘accept no government position which it cannot conquer through its own strength at the ballot box’. He denounced Millerand’s stand by saying that ‘what good Millerand may have done is claimed for the credit of the bourgeois republican government: what evil the cabinet has done reflects back on the reputation of the socialist parties. Heads they win, tails we lose.’ Connolly would ignore his own earlier advice.

Sean O’Casey concluded that in 1916 ‘Jim Connolly had stepped from the narrow byway of Irish Socialism onto the broad and crowded highway of Irish Nationalism’ and in his History of the Irish Citizens Army wrote ‘Liberty Hall was no longer the Headquarters of the Irish Labour movement, but the centre of Irish national disaffection’. Like most ‘socialist leaders’, Connolly surrendered to patriotism in 1914 but in his case it was Irish patriotism. He signed the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, a document with little socialist content, presenting no recognition of the existence of conflicting classes, and steeped in deep religious piety, beginning as it did, ‘Irishmen and Irishwomen: in the name of God and of the dead generations from which she receives her old tradition of nationhood, Ireland, through us, summons her children to her flag and strikes for her freedom’ and ending ‘We place the cause of the Irish Republic under the protection of the Most High God’

Wrong tactic

After one week of fighting the 1916 Dublin Uprising was bloodily suppressed. Lacking any real basis of support, the insurgents did not have much chance of victory. The idea that people can be incited into action by heroic example is a false one, later proven in Germany in 1921 and 1923. Only when the conditions for struggle actually exist, only when the majority of people are prepared to do battle and make enormous sacrifices, can a revolution be achieved. Many of those who advocate the false tactics of the barricades and street-fighting today draw, in part, their inspiration from the Easter Rising. If they removed their blindfolds they would discover that the actual experience of the rising proved the futility of such action. The conditions for a successful revolution expressly did not exist in 1916. They did not exist in Ireland and they did not exist in Europe. In Ireland, the Irish Republican Brotherhood and the Citizen Army were only a relative handful in number. The revolutionaries hoped that the country would follow them – but nothing happened. Despite his knowledge of Marxism, Connolly forgot that it will take the working class to change society, not a handful of individuals to do it for them. The fact also remains that Connolly, although credited as a socialist scholar, failed to appreciate Engels’s counsel in 1895 that the time for street-fighting, barricades, conspiracies and insurrections had passed and that it was now time to recognise as the most immediate task of the workers’ party the slow work of propaganda and electoral activity. Connolly made the glaring error of believing that the British state was incapable of using heavy artillery and so destroying its own property. In fact, the British readily bombarded buildings.

Connolly’s stature is due to his death and martyrdom but what did his blood sacrifice produce? We can speculate on Connolly’s role if he had survived and perhaps offer the example of Countess Markiewicz, who became Minister of Labour in the first republican government and died a firm supporter of De Valera.

James Connolly tried to stand with a foot in both the socialist and nationalist camps simultaneously. Like the left nationalists of today, he hoped that the bulk of nationalist supporters would learn in the course of the independence struggle to throw in their lot with the socialist movement. Unfortunately, that was not to be, as the siren call of the national patriot proved stronger than the appeal to class solidarity. The Socialist Party rejects nationalism as anti-working class because it has always tied the working people to its class enemy and divided it amongst itself.

ALJO