In the British shipbuilding industry, 1968 was greeted with tepid optimism. The optimism was based on the hope that world shipbuilding may at last have recovered from the slump which followed Suez and the conviction that the British industry is about to solve some of its longest standing production problems. But it was kept tepid by the memories of the slump, by the continued presence of uncertainty, and by the low standing of British shipbuilding in the world market

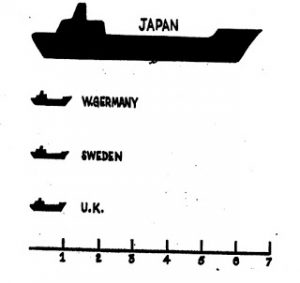

(See Fig. 1).

The slump which started in 1957 was peculiar in that it came at a time of virtually full employment in developed countries and when the volume of world wide sea traffic was increasing. It was caused by the market proving to be smaller than the shipowners, who are only human and who cannot control or predict the anarchies of capitalism, had estimated.

This misjudgement was widespread. Not just the tramp owners but also the big oil companies, the steel firms, even the United Nations, thought there would be more sea-borne traffic than there turned out to be. The reopening of the Suez Canal in 1957 and the cancellation of the contracts for millions of tons of American coal for Europe contributed to the crash. When it came, shipbuilding prices fell by about 40 per cent over some three years and brand new tankers were being taken direct from launching to be laid up, some of them for years.

This typically capitalist mess was put to rights, slowly, not because of any acumen by the shipping men but by the continuing increase in world trade and the scrapping of some of the older ships. The Liberty ships, for example, which flooded out of American shipyards during the war, are now undergoing their sixth special survey—a rigorous examination which may be so costly to pass that it is cheaper to scrap the ship.

For the time being, then, the outlook is slightly better for the shipyards. “We enter 1968 with future commercial prospects brighter than for some years past . . .” said M. A. Scott, President of the Shipbuilders and Repairers National Association (Times 1/1/68.) But at best this is a fragile hope.

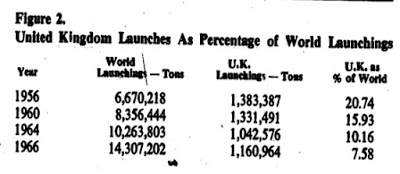

In 1966 British shipyards were responsible for something like 7½ per cent of world launchings. Fig. 2 shows how the British share of an expanding market is steadily shrinking. What it does not show, however, is the historical scale of this decline—the slide from the days when British shipbuilding dominated the world.

|

| Figure 1. Launchings during 1966 (Million tons gross) |

In the 1880’s, at the peak, something like 85 per cent of all ships launched in the world were built in Britain. It was not until the First World War that this share fell below 50 per cent. During the Thirties it fluctuated; after 1945 shot up- to about 55 per cent and since then has steadily fallen. (See Shipbuilding by A. C. Hardy and E. Tyrrell.)

This decline has not been caused by any reduction in the productive capacity of British yards, which remains at about 1¾ million tons, but rather by an increase in the output of other countries which have successfully modernised their yards, applied new techniques and undercut British prices. Hardy and Tyrrell had this to say about the stagnation in Britain:

The present stage is one of transition and, in British yards at any rate, it is likely to continue for perhaps another twenty- five years, because of physical limitations in the shipyard areas on the one hand and of the economic difficulty of scrapping existing and well-tried establishments and valuable equipment on the other.

Foreign competition is the bogyman of British shipbuilding, none of it more frightening than the Japanese. In 1955 Japan was producing about half the tonnage of Britain; by 1966 they were making about six times as much. In May 1963, when Court Line ordered a 67,000 ton tanker from Japan, the Guardian commented:

This is the first time Court Line has built abroad. It is not the first British flag vessel to be ordered in Japan, but it is certainly rare enough to come as quite a jolt to our shipbuilding industry. (23/5/63.)

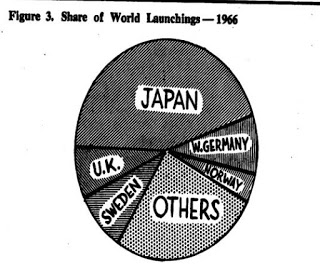

Nowadays this event has become more familiar. Even the mighty P & O group, British from stem to stern, has had some of its latest express cargo liners built in Japan and so have Blue Funnel Line and Glen Line. (See Fig. 3.)

The British firms have blamed this onto certain advantages which, they say, their foreign rivals have over them—better credit and loan terms, cheaper steel, a more docile labour force, Whatever the truth of this applied to Japan; it is hardly true of Sweden whose wages and steel prices are high but whose ships are strongly competitive.

This is the situation which gave birth to the Geddes Commission, which investigated British shipbuilding and reported in 1966. As a result the government have introduced the. Shipbuilding Industry Bill, under which loans up to £200 million at any one time will be guaranteed for orders placed with British yards. (This was, in fact, higher than the Geddes recommendation). Geddes also came down for a 10 per cent cut in the price of ship steel (negotiations on this should come to a head this Spring) and for a series of mergers among the shipbuilding firms (many of these have already happened, others are now being talked about).

The other issue—probably the thorniest of the lot—may also be settled some time this year. The men who build the ships. Shipyard workers are among the toughest and have a reputation for prolonged disputes over who-does-what. Their work is hard, dirty and dangerous. Because shipyards, like coalminers, can be built only at certain places, their workers live in concentrated communities near the yard, which makes their unity in disasters, slumps and disputes more solid.

The memories of previous slumps—of Jarrow, of the hulk of the Queen Elizabeth rusting above the houses on the Clyde —hang on. The shipworkers’ unions have a healthy mistrust of new productive methods which mean more intense exploitation and probably sackings. Their policy has been to sell themselves as dearly as they can, and to fight every inch of the way—even if this meant arguing over who bored a hole or who chalked a line.

The Geddes Commission recommended a reduction in the number of shipyard unions, from about 15 to five, and many changes in conditions of employment, apprenticeship and so on. The unions have already said they are willing to sit down and talk and Dan McGarvey, President of the Boilermakers’ Amalgamation, has promised that there will never be another demarcation dispute between shipyard unions.

This, then, is a time of change for British shipbuilding. Geddes hoped that after two or three years of reorganisation the U.K. industry’s share of the world market should increase to at least 12½ per cent and production should rise to around 2¼ million tons.

But only a year ago, as the Shipbuilding Industry Bill, on which so many hopes are pinned, was published, the Shipbuilding Conference was drawing attention to the fact that “. . . it would be misleading not to recognise the present weak state of the international freight market.” This is something which no amount of reorganisation in shipyards and unions can change; and it could get worse. Peace in Vietnam for example, would probably release a flood of shipping looking for freight and upsetting many plans for new ships. Also no one is yet certain about the effect which the container ships will have on the number of ships needed on the busier trade routes.

In face of another slump Geddes would be seen for what it is—another desperate stop-gap for one of capitalism’s insoluble problems. Capitalism can never tell what is around the next comer; shipbuilding cannot see over the top of the next wave.

Ivan

(Figs 1, 2 and 3 are compiled from figures published in Lloyd’s Register of Shipping Annual Summary of Merchant Ships Launched During 1966.)