A Patriotic Swindler: Horatio Bottomley

March 23rd, 1960, marks the centenary of the birth of Horatio Bottomley, one of Britain’s most colourful and well-loved figures of the period 1890-1920. Yet this popular figure, who became almost synonymous with John Bull, was one of the greatest rogues alive, getting through in a day at the races more than many of his constituents in South Hackney earned in several years. And the money was always somebody else’s; he was not even a Capitalist, he was a common swindler puffed up by his great flair for sensational journalism and by posing as John Bull, the Sporting Britisher’s man.

The early part of Bottomley’s career, the years 1890-1914. could well be called the Golden Age of British Capitalism. It was an age of great upper-class luxury; it was a flamboyant, opulent age. It was also an age of great optimism. Imperialism was at its height, the Sun never set on the Empire, all problems could be solved by the normal workings of Capitalism, Society was an unshakable rock. Men basked in the false sunshine of Prosperity—even those who were poor. Workers shared in the general optimism; if there was great poverty, there was also the great illusory promise of things to come. There were clouds drifting across the sun. the largest being the tremendous growth of Germany as an industrial, military and naval power, but these clouds scarcely disturbed the illusion of opulent serenity of Sporting Edward’s reign.

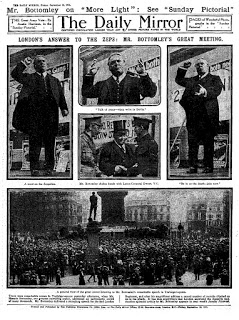

Bottomley had many of the upper-class attributes of the time. He loved racing, champagne, pretty girls, money and power. And he displayed his likes in the arrogant, showy way so typical of the age. His long period of success can only be understood by seeing the man in his context. He was an important figure in finance, a great journalist, a clever lay lawyer, a tremendously effective orator, a man to whom the electors of South Hackney delighted to give their votes, and he was a leader of “Public Opinion.” He was a patron of the poor, the friend of the rich and influential, a champion of the moral virtues and defender of the family, an incessant campaigner (through the pages of John Bull) against prudes, indecency, brutality and corruption. He was a “sport”; and he was the biggest liar and hypocrite in England. He was a man incapable of real generosity; a man who, to quote an old inhabitant of Hackney, “would give a 5s. tip and pinch the bread-and-cheese out of your pocket.” He appears a cardboard figure today, his actions all deliberate poses for the benefit of an admiring public. Yet he inspired real devotion in his assistants; perhaps in that age nothing succeeded so well as success, particularly success at large-scale swindle.

Bottomley lived during the great days of company flotation. The law was comparatively lax, and Bottomley infinitely audacious. He early acquired a taste for bankruptcy; a taste that harmed nothing except his political ambitions, for he lived as richly as when he was solvent. He floated many companies, and their funds stuck to his eternally sticky fingers in enormous quantity. He was prosecuted quite early in his career, and conducted his own defence in an able and witty manner. So well-liked was he that many of his victims still had faith in him and his enterprises, and even shared the jokes he made in Court at their expense. The Company schemes were difficult to unravel, the organisation chaotic, the book-keeping almost non-existent. His assistants could be relied on to be helpful in the most obstructive possible way when the Official Receiver and his agents were endeavouring to inspect the books. He was a ferret squeezing through every loophole in the Company laws.

Perhaps his greatest achievement was his building-up of John Bull into a best-seller among journals. This was one Bottomley venture which was quite safe from the law, for business and financial management was firmly in the hands of Odham’s. Bottomley drew a large salary as managing Editor, a salary which was considerably augmented by the firms who paid not to appear in its pages, and by the lotteries, competitions and share-subscription schemes advertised in the journal! These schemes placed enormous sums in Bottomley’s pocket. Through John Bull he not only raised money, he became an expert manipulator of Public opinion. His appeals to patriotism, his nauseating anti-Germanism during the first world war, his attempts to found a new political party, all pointed to the incipient demagogue. As he grew older, his love of power grew and his astuteness declined. After the war he hastily secured his discharge from bankruptcy (characteristically. with money not all of which was his own) in order that he could take part in the 1919 election. He finally came to grief over his share-subscription schemes, being prosecuted under the Larceny Act of 1915, an Act which was passed to prevent the depredations of Bottomley and others of his kind.

schemes placed enormous sums in Bottomley’s pocket. Through John Bull he not only raised money, he became an expert manipulator of Public opinion. His appeals to patriotism, his nauseating anti-Germanism during the first world war, his attempts to found a new political party, all pointed to the incipient demagogue. As he grew older, his love of power grew and his astuteness declined. After the war he hastily secured his discharge from bankruptcy (characteristically. with money not all of which was his own) in order that he could take part in the 1919 election. He finally came to grief over his share-subscription schemes, being prosecuted under the Larceny Act of 1915, an Act which was passed to prevent the depredations of Bottomley and others of his kind.

schemes placed enormous sums in Bottomley’s pocket. Through John Bull he not only raised money, he became an expert manipulator of Public opinion. His appeals to patriotism, his nauseating anti-Germanism during the first world war, his attempts to found a new political party, all pointed to the incipient demagogue. As he grew older, his love of power grew and his astuteness declined. After the war he hastily secured his discharge from bankruptcy (characteristically. with money not all of which was his own) in order that he could take part in the 1919 election. He finally came to grief over his share-subscription schemes, being prosecuted under the Larceny Act of 1915, an Act which was passed to prevent the depredations of Bottomley and others of his kind.

schemes placed enormous sums in Bottomley’s pocket. Through John Bull he not only raised money, he became an expert manipulator of Public opinion. His appeals to patriotism, his nauseating anti-Germanism during the first world war, his attempts to found a new political party, all pointed to the incipient demagogue. As he grew older, his love of power grew and his astuteness declined. After the war he hastily secured his discharge from bankruptcy (characteristically. with money not all of which was his own) in order that he could take part in the 1919 election. He finally came to grief over his share-subscription schemes, being prosecuted under the Larceny Act of 1915, an Act which was passed to prevent the depredations of Bottomley and others of his kind.Bottomley was a liar, a thief, and a hypocrite. Yet for thirty years he remained an important, imposing figure in English life. His popularity with the many members of the upper class is easily explained. His depredations scarcely affected them, he was clever and a good conversationalist, he shared their tastes, and he was, as a “man of the people,” a useful figure, particularly during the war. Their sympathy had lessened by the end of his career. His growing interest in politics was becoming an embarrassment: as a demagogue he might threaten their own privileged positions.

To many workers he was a “sport”: they lived vicariously through his extravagances, and he posed as their champion. A reading public—unsophisticated, untrained in politics, crushed by poverty and eager for sensationalism—was provided for him and his kind by the Education Acts of the late 19th century.

After his imprisonment, he found he was unable to make a success of a new journal on the lines of the old John Bull. His popularity had vanished, his journalism had become out of date, his utterances old-hat and naive-sounding. He died in poverty, denied even the comfort of an old-age pension.

His greatest crime went unpunished, and was indeed applauded and highly-paid; he was one of Capitalism’s greatest Recruiting Sergeants.

F. R. Ivimey