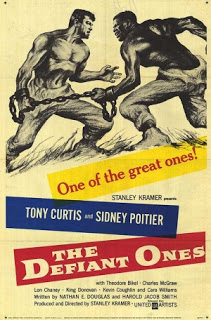

The Defiant Ones (Directed by Stanley Kramer)

The Defiant Ones (Directed by Stanley Kramer)In 1948 Stanley Kramer formed his own film company with Carl Foreman. He produced a number of films that were, to quote “Sight and Sound”—“courageously off-beat.” In 1950, under agreement with Columbia, he produced more “off-beat” pictures, among them “Death of a Salesman.” The critics began to take notice. Eight years later, film-goers are catching up, and his latest film “The Defiant Ones,” which he produced and directed, has not yet received an adverse review.

Kramer has now become one of America’s leading producers with an eye to controversial subjects and new methods. Posters for “The Defiant Ones” carry a list of newspaper blurbs that would make Cecil B. De Mille envious. The film has in fact even been serialised in the Daily Express, so setting the seal on success. It seems that Kramer is now established after an erratic beginning. Audiences now know him and want for more.

“The Defiant Ones” is a story of two convicts, one a negro and the other white, who defy the written and unwritten laws of the land (The American South) by making for freedom and making for friendship. They are Joker Jackson (Tony Curtis), a brash white youth whose aggressive attitude results from being pushed around by rich men, and whose bigoted hostility to Noah Cullen, the negro, is a result of being brought up in America; and the negro (played by Sidney Poitier). an embittered, cynical man whose bitterness lies in the whole racial issue.

Chained together, they both escape from the state police after a road accident. Moving through rough country they are pursued’ by a sheriff with state police and sworn-in deputies from surrounding farms. The convicts flee to the North, all the time with their antagonism graving. Though it is the general opinion that they won’t go five miles without killing each other, they manage to stay on the loose, narrowly avoiding a lynching party and ending up with a lovesick woman and her son. The woman takes a fancy to Jackson and suggests they both escape in her car to the big city. Her husband has left her and she is full of get-away-and-go-places dreams (which have no place for the negro). Finally, they all agree upon it, and Cullen makes his own way North, leaving Jackson with the woman and her son. Later. Jackson discovers that the woman has given the negro directions that will lead him into a treacherous swamp.

Negro and white are together again when Jackson realises the friendship that he has for his companion. They both travel towards the railroad and wait at a bridge to jump a freight to freedom. Cullen scrambles on to the train, but Jackson, who was shot by the woman’s son when he ran from their house, has no strength left, but grasp’s the negro’s hand (as in earlier shots of the two hands chained together) and tries to pull himself on. They end up by toppling down an embankment to be captured by the police.

The film is from beginning to end an allegory. A scratching upon the surface of the race problem that gets nowhere, but shows that both black and white workers are pushed around all their lives. In the dialogue, the two convicts are discussing their ideas of the world. The white is bitter about his old job as a garage attendant where he had to say “thank you” for a living. The negro talks of the land he once tended with his wife, dispelling Jackson’s ideas of “a farm of your own.” Cullen worked hard all day, but was still hungry. They argue and Jackson, slighted by this, makes believe that when they are free he will go into a large hotel, but throws at Cullen, “you will have to go in the back door,” with Cullen rejoinding, “while you go in the front door just low enough to collect your tip.” This sums up the situation that both black and white workers have to work all the time or starve. Race prejudice on the part of white workers towards black or Jewish or Chinese workers is but a reflection of their own insecurity and ignorance of Capitalism.

No film has been made that shows racialism for what it is, one of the group antagonisms of Capitalism, but “The Defiant Ones” is about as far as any film maker can get with the colour problem. It is, though, a film of great qualities. Kramer is a director of merit, with ideas and techniques that make this film, which could easily have been a flop, a success. The handling of the posse sequences, with police, hounds and rock ‘n’ roll from a portable radio accurately give the atmosphere of the lawful hunting the convicts, the dangers to society. The superficial aspects of race prejudice are expertly presented with feeling and understanding. The episode of the lovesick woman also indicates this.

“The Defiant Ones” contrives real tension and suspense in a record of a pathetic attempt by two men to escape from the law. and their success in defying the prejudice that they have always known. Their escape is summed up by a character who lets them free after they have been captured by a lynching mob. He watches them escape with the words. ‘‘Run chicken . . . run! ” The racial issue is summed up by Cullen and Jackson just before they are captured. They both lay exhausted, and the negro sings a bitter blues that has run throughout the film at intervals. Gun in hand the sheriff of the posse approaches then puts it away when he sees the fugitives together nursing their wounds and thinking they have had a good run for their money. He stares quizzically and the negro spits out the final line of the song at him, smiling contemptuously.

Robert Jarvis