P R E F A C E

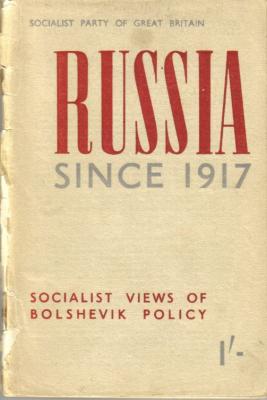

This pamphlet consists of articles published originally on the Socialist Standard. It is a record, in collected form, of the attitude of the Socialist Party of Great Britain to events in Russia since 1917. In March of that year the Czarist regime collapsed and was followed, after short-lived stop-gap Ministry, by the Kerensky Government which was a coalition of various reformist parties. This Government was opposed by the Bolsheviks who, under the leadership of Lenin and Trotsky, overthrew it and seized power in October, 1917.

In the articles themselves, no attempt has been made to interfere with the original texts. The articles stand just as they were written. We have nothing to fear from letting our original words stand. There are, it is true, passages in some of the earlier articles which, were we writing to-day in the light of information now available, we would phrase differently; but these are points of detail. In essentials, these articles stand as overwhelming testimony to the soundness of the Marxist position, the position of the Socialist Party of Great Britain.

A word of explanation may be needed about the first of the articles reprinted below – “A Russian Challenge.” In February, 1915, a conference was called by the social-democratic parties of the Allied countries, then at war with Germany and her partners, for the purpose of discussing war aims and the prosecution of the war. The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolshevik Party), which opposed the war, was not invited. Unable to get their views published in the journals of the parties supporting the war, they approached the S.P.G.B., and their statement appeared in the Socialist Standard of March, 1915. It is reproduced here as an indication that our opposition to Bolshevik policies was not the outcome of prejudice; we were at all times ready to give them credit when their actions in line with the interests of the working class. Under each title the date of publication in the Socialist Standard is given in brackets.

The Executive Committee of the Socialist Party of Great Britain

June, 1948

CONTENTS

1. A Russian Challenge

2. Prelude to Bolshevism

3. The Russian Situation

4. The Revolution in Russia

5. A Socialist View of Bolshevik Policy

6. The Super Opportunists

7. The Passing of Lenin

8. Trotsky states His Case

9. Russia: Land of High Profits

10. Changing Russia

11. The “Terrorist” Trial

12. The New Constitution

13. Birds of a Feather

14. War Overtakes Russia

15. Inglorious End of the Comintern

16. Is Russia Socialist?

17. “Local Boy Makes Good”

18. Russia and Democracy

19. From Comintern to Cominform

20. The Daily Worker and Lenin on Equal Pay

21. Russian Imperialism

Postscript

1) A RUSSIAN CHALLENGE

(March 1915)

We have received the following and publish it in order to show the trickery resorted to by the pseudo-Socialists responsible for the London Conference in endeavouring to exploit the Russian Socialists , whose challenge they dare not face.

A DECLARATION TO THE LONDON CONFERENCE

Comrades, – Your Conference calls itself a conference of the Socialist parties of the allied belligerent countries, Belgium, England, France and Russia.

Allow me first of all to draw your attention to the fact that the Social-Democracy of Russia, as an organised body, as represented by its Central Committee and affiliated to the International Socialist Bureau, has received no invitation from you. The Russian Social-Democracy, whose views have been expressed by the members of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Group in the Duma, now arrested by the Tsar’s Government (Petrovsky, Muranoff, Badaoff, Samoiloff representing the workers of Petrograd, Yokaterinoslaff, Kharkoff, Kastroma and Vladimir districts) have nothing in common with your conference. We hope that you will state so publicly, as otherwise you may be accused of distorting the truth.

Now allow me to say a few words with regard to your conference, i.e., to tell you what the class-conscious Social-Democratic workers of Russia would expect from you.

We believe that before entering upon any deliberations with regard to the reconstruction of the International, before attempting to restore international bonds between Socialist workers, it is our Socialist duty to demand:

(1) That Vandervelde, Guesde and Sembat immediately leave the Belgian and French bourgeois ministries.

(2) That the Belgian and French Socialist parties break up the so-called “block national” which is a disgrace to the Socialist flag and under cover of which the bourgeoisie celebrates its orgies of chauvinism.

(3) That all Socialist parties cease their policies of ignoring the crimes of Russian Tsarism and renew their support of that struggle against Tsarism which is being carried on by the Russian workers in spite of all the sacrifices they have to make.

(4) That in fulfillment of the resolutions of the bale conference we hold out our hands to those revolutionary Social-Democrats of Germany and Austria who are prepared to carry on propaganda for revolutionary action as a reply to war. The voting for war credits must be condemned without any reserves.

The German and Austrian Social-Democrats have committed a monstrous crime against Socialism and the International by voting war credits and entering into domestic truce with the Junkers, the priests and the bourgeoisie, but the action of the Belgian and French Socialists has by no means been better. We fully understand the conditions are possible when Socialists as a minority have to submit to a bourgeois majority, but under no circumstances should Socialists cease to be Socialists or join in the chorus of bourgeois chauvinism, forsake the workers’ cause and enter bourgeois ministries.

The German and Austrian Social-Democrats are committing a great crime against Socialism when, after the example of the bourgeoisie they hypocritically assert that the Hohenzollerns and the Hapsburgs are carrying on the war of liberation “against Tsarism.”

But those are committing a crime no less stupendous who assert that Tsarism is becoming democratised and civilized, who are passing over in silence the fact that Tsarism is strangling and ruining unhappy Galicia just as the German Kaiser is strangling and ruining Belgium, who keep silent about the facts that the Tsar’s gang has thrown into gaol the parliamentary representatives of the Russian working class, and only the other day condemned to six years penal servitude a member of Moscow workers for the only offence of belonging to our party, that Tsarism is now oppressing Finland worse than ever, that our Labour press and organisations in Russia are suppressed, that all the milliards necessary for the war are being wrung by the Tsar’s clique out of the poor workers and starving peasants.

On behalf of the Central Committee of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party,

London, February 14th, 1915. M. MAXIMOVICH.*

* The Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party, also known as the Bolshevik Party, later changed its name to Communist Party.

“ M. Maximovich” who signed the statement is Maximovich Litvinoff, Commissar for Foreign Affairs 1930-1939.

************************************************************

2) PRELUDE TO BOLSHEVISM

(MAY 1917)

The revolution in Russia and the attitude now adopted by the war party in the country toward the new government of Russia affords an interesting study to the detached onlooker. For thirty months the “speedy prosecution of the war” party have referred in glowing terms to “our gallant ally, Russia,” and a lickspittle Press has given her the necessary puffs periodically. Now much of it is changed; with the revolution, lo and behold! we are informed that the Tzar was weak – was influenced by the German-born Tzaritza – the Court corrupt, and those in control were trying to bring about a separate peace with Germany. Strange, is it not, that when previously rumors were in circulation here with regard to a separate peace, the war party repudiated any such intention on the part os “our gallant ally.” Today Parliament and Press are applauding the overthrow of the Tzar and his Government, whom they have been allied with so long, and telegrams of congratulation are sent to the new President of the Duma.

All the information available, both past and present, shows quite clearly that the upheaval in Russia is not a revolution of the working class, clearly seeing its slave position under the old order and setting to work in an organised fashion to emancipate itself. Far from this is the truth, we are sorry to say. It is but another example of the capitalists using the discontent and numbers of the working class in Russia to sweep away the feudal rules and restrictions so strongly symbolized in the Czar and the Council of Nobles, and to establish a system of government in line with modern capitalist needs and notions.

Hence the welcome given to the revolution, not only by the capitalist governments in their official capacity, and also by their various hangers-on, like Hyndman, Kropotkin, the B.S.P., I.L.P., etc.

According to the report in the Daily Telegraph of 18th April, 1917, the Duma gave a great welcome to the decoy ducks of the British Government, Messrs. W. Thorne, G. O’Grady and W. S. Sanders. These individuals were sent out by the Government as representatives of the “Labour” movement here, although not a single organisation of workers was consulted as to their views on the matter, nor was their choice asked in reference to a representative. The “Labour” organisations have been completely ignored in the matter, and the individuals referred to have been chosen by the Government because of their peculiar fitness to perform the dirty work required to be done.

************************************************************

3) The Russian Situation

(JANUARY 1918)

The doings of the Bolsheviks is the topic of the moment. They dwarf all other events connected with the war. We are not in a position to say much regarding the position of affairs in Russia, for we have little information regarding it beyond the lying messages of our masters’ lickspittles.

. . . . . . . . .

Whatever may be the final outcome, the Bolsheviks have at all events succeeded in doing what all the armies, all the diplomats, all the priests and primates, all the perfervid pacifists of all the groaning and bleeding world have failed to do – they have stopped the slaughter, for the time being, at all events, on their front.

How much more than this they ever intended to do the future may reveal. They may have higher aims, yet to be justified by success or condemned by failure; but it is an astounding achievement that these few man have been able to seize opportunity and make the thieves and murderers of the whole world stand aghast and shiver with apprehension. The British Ambassador would not recognise them, but the British Ambassador is coming home, we are told, and some one “in marked sympathy with the Bolshevik Government” is to be appointed in his place. The Germans arrest Socialists all over Germany, and are at once reduced to denying the fact when Bolsheviks declare that Socialists everywhere are under their protection. The Bolsheviks publish their demands, and immediately the Allies’ war aims are whittled of most of their truculence and proclaimed from the housetops. Verily, not all the decisions of capitalist hirelings can hide the fact that all the belligerents are uneasy in the face of Bolshevik success.

************************************************************

4) The Revolution in Russia: Where it Fails

(AUGUST 1918)

By far the most important event in the social sense, which has occurred during the world war has been the upheaval in Russia, culminating in the revolution of March and November, 1917. For the working class these events are of supreme interest and worthy of close and deep study, not only for the purpose of keeping in touch with events as they occur, but also for learning the lessons these may impart.

Just here, however, the working class of Great Britain are faced with a most formidable obstacle in the way of their gaining even a slight knowledge of the happenings, or reaching a position where a full consideration could be given to the facts of the revolution. This obstacle is the Defence of the Realm Act.

By operations of this Act the master class sift all news coming into the country, by either Press or post, and take care that only matters allowed to be published are those that suit the interests of this class in one form or another. Thus, quite apart from their ownership of the General Press, they are able to prevent groups or individuals in this country obtaining information that might be useful to the working class. In other words, the only information or statements anyone outside of government circles can obtain here is just what it suits the master class to allow them to have.

In spite of this simple and glaring fact the I.L.P. have not hesitated in to denounce the action of November, usually called the “Bolshevik Revolution,” while the S.L.P. has acclaimed it as a great Socialist revolution. Point is added to these facts by the appearance of two pamphlets written not only by Russians, but by men claiming to be Bolsheviks. Here, if anywhere, one might imagine, will be found useful information, concrete facts, detailed accounts of events, that would be useful in guiding us to a sound judgement. Unfortunately, nothing whatever is told in either pamphlet, apart from expressions of opinion, except the statements already given in the capitalist Press, which for the reasons above must be taken with the utmost caution.

The first pamphlet is entitled: War or Revolution, is written by Leon Trotsky, and is published by the S.L.P. at Glasgow. No date of its writing is given, but from internal evidence it was seemingly written in 1915—before the fall of the Czar—and appears to have been originally published in America.

While claiming to be a Marxist Trotsky appears surprised at the actions of the so-called Socialist International in voting war credits and supporting the war. To any serious Marxian student this was only to be expected. The Socialist Party stands firm and solid on the line of the class war. Only here is he impregnable. Only on this basis can the workers organise successfully for the overthrow of capitalism. For years past the S.P.G.B. alone in this country, and the Marxist groups in other countries, have pointed out that sections from England, France, Germany, Italy, Austria, etc., that formed the majority of the International, either had abandoned, or had never taken up, a stand upon the class war, and were therefore really not Socialists in the proper sense of the word. Their actions when the war began and since have simply emphasised the truth of our former case. That it took this world-slaughter to enlighten Trotsky as to the real position of these sections shows how little he grasped their actual attitude before. He is equally mistaken in his judgement of events in England, for on p.16 he says:

“In England the Russian Revolution [1905] hastened the growth of independent Socialism.”

Quite apart from the fact that the 1905 upheaval in Russia was a capitalist and not a Socialist movement, this statement is absolutely incorrect. A movement that is not independent cannot be Socialist, and the Russian episode had no measurable effect upon either the Labour or the Socialist movement in this country. The real break with the old compromising policy that had saturated the movement in England, took place in 1904—a year before the Russian outbreak—when the Marxists formed up in the Socialist Party of Great Britain.

Equally mistaken is Trotsky’s statement on the same page that “six or seven years ago [that is six or seven years before 1915] in England, the Labour Party, after separating from the Liberal Party, entered into the closest association with it again.” As every student of the history of the Labour Party knows, that party has never been out of the “closest association” with the Liberal Party since the day it formed. Just as incorrect is the phrase in the concluding section (p.27) where the author say: “Socialist reformism has actually turned into Socialist imperialism.”

Reformism and Imperialism are capitalist, and can by no stretch of the imagination be called Socialist. Such misuse of the latter word, especially by one claiming to be a Socialist, is a direct assistance to the master class in their endeavours to further confuse the minds of the working class by misrepresentation of various kinds.

The second pamphlet was written by M. Litvinoff in March 1918, but it adds nothing to our knowledge of affairs in Russia, as it simply consists of a selection of the statements that have appeared in the capitalist Press of this country. In some instances these statements are exceedingly useful against agents of the master class like Kerensky, and we have used these admissions ourselves in the SOCIALIST STANDARD when Kerensky was in power. Some of the other statements are significant in their bearing on the actions of the workers in Russia in a manner unsuspected of Litvinoff.

One feature of extreme and peculiar importance in these movements is treated by both the above writers in exactly the same manner, i.e., with silence. This feature is the economic and social position of the working class in Russia. For a matter of such importance to be neglected by both writers, shows either a lack of knowledge of the Russian situation or a deliberate attempt to conceal such knowledge from their readers. As two such Russians are either unable or unwilling to supply this information the only thing left is to take that available before the war and try to apply it to the solution of the present situation. Clearly this can only be a provisional judgement while awaiting reliable news of the revolutions and of the present position of the workers in Russia.

Even to-day Russia is largely an agricultural country, some authorities stating that 80 per. cent of the population are engaged in that calling. Their system, however, has certain peculiar features that would take a large volume to describe.

In the main the agricultural population is divided up in village groups or communities largely based on what is called the “Mir.” Each peasant is allotted a certain amount of land, depending on the number of his family. The holdings are changed periodically so as to prevent any one individual retaining the best land. If the population increases beyond the limits of the land controlled by the “Mir,” a group forms up and moves out to new lands in a manner so well described by Julius Faucher in his brilliant essay on The Russian Agrarian System. As this group is related to the old “Mir,” communication and intercourse are kept up and a division of a race may have a whole series villages spread out over a certain area, and having a more or less loose connection with each other. The land, however, is not owned by the village group. In the ultimate it is owned by the Czar in his capacity as “Father of the People” though large number of estates have been granted to the Nobles for their military and other services rendered to the Crown.

This ownership, whatever particular form it may take, is admitted by all the “Mir” by the payment of a charge for the land, usually termed a tax. This tax is paid to the Noble where he holds an estate and to the Czar where the latter is personal owner.

Into the developments, complications, abuses and rogueries that have resulted from this system we have not the space to go. One illustration can be found in Carl Joubert’s Russia as it really is and Stepaniak in his Russian Peasantry, has given a masterly description of its workings. It will be sufficient to point out that apart from minor modifications three broad divisions have developed.

In the wild forest regions of the North, the people are still in the upper stage of Barbarism, being a mixture of hunters and pastoral workers, who know practically nothing of the affairs of the outer world. In the middle regions the spread of the use of money and the effects that follow have resulted in more modern methods of working the estates. Owing to the heavy tax imposed large numbers of peasants have been unable to pay this charge after a poor season, with the inevitable result that they fall into the hands of money-lenders—who in numerous cases are actual members of the “Mir”—or they have to give up their holdings and either work for the money-lender or drift into the towns in search of work.

In the South or “Black Belt” region, largely owing to the fertility of the soil, old-fashioned methods still persist and the peasants make desperate struggles to retain their holdings, but were slowly losing their grip before the war.

The abolition of serfdom on private estates in 1861 and on the Czar’s estates in 1871, was loudly announced as a great emancipation of the peasants. Under these decrees the peasants were supposed to be placed in a position were they could purchase their holdings, either individually or as a village group or Mir. The Nobles, of course, still retained the bulk of the estates granted to them, and it was intended that the big landlords would be balanced in the social system by the large number of small owners or peasant proprietors that would be sure to follow the great act of “emancipation”. In the vast majority of cases, of course, the whole thing was a fraud and the landlords and moneylenders being the only ones, as a rule, able to purchase land, we have the paradox that the measure introduced to extend peasant proprietorship has resulted in the concentration of large estates in fewer hands than before. This has increased the number of landless peasants which recent estimates have placed at about one-third of the agricultural population, while even those who favour the system do not claim that more than another third have become owners of the land, either individually or through their village groups. The local affairs of the Mir are managed by the open general meetings, and these meetings elect the Elder or Mayor, who is the spokesman and delegate before the authorities. As stated above, the moneylender of the village is often a member of the Mir, and owing to his economic hold on the peasants he is often elected as the Elder.

It was, and is, people of this type that Kerensky represents. The Mir, of course, is under general Government control, usually through a “superintendent” or police officer.

In the Western area and the Southern Oil Belt industrial towns of the usual capitalist type, have developed in late years, and contain a number of genuine proletarians or wage slaves.

Is this huge mass of people, numbering about 160,000,000 and spread over eight and a half millions of square miles, ready for Socialism? Are the hunters of the North, the struggling peasant proprietors of the South, the agricultural wage slaves of the Central Provinces, and the industrial wage slaves of the towns convinced of the necessity, and equipped with the knowledge requisite, for the establishment of the social ownership of the means of life?

Unless a mental revolution such as the world has never seen before has taken place, or an economic change has occurred immensely more rapidly than history has recorded, the answer is “No!”

And it is extremely significant that neither Trotsky nor Litvinoff say a single word on this aspect of the situation. In fact, as far as one can judge, the best, but all too brief, account of the present position in certain parts of Russia is given by Mr. Price in his articles in the Manchester Guardian during November and December, 1917.

Leaving aside the subsidiary differences in the economic positions of the different provinces, the one great fact common to the mass of the peasantry is their desire to be rid of the burden of the tax they have to pay for their land, whether to the local lord or to the Government, so that they may gain a livelihood from their holdings. This applies to both the individual and the group holders. Hence the peasants’ movements are not for social ownership, but merely for the abolition of the tax burden and their right to take up new land as the population increases. In other words, they only wish to be free the old system of individual or group cultivation from governmental taxes and control. The agricultural and industrial wage-workers would be in a similar position economically as the same class of workers in Western Europe, if allowance is made for the lesser capitalist development of Russia.

What justification is there, then, for terming the upheaval in Russia a Socialist Revolution? None whatever beyond the fact that the leaders in the November movement claim to be Marxian Socialists. M. Litvinoff practically admits this when he says (p.37):

“In seizing the reigns of power the Bolsheviks were obviously playing a game with high stake. Petrograd had shown itself entirely on their side. To what extent would the masses of the proletariat and the peasant army in the rest of the country support them?”

This is a clear confession that the Bolsheviks themselves did not know the views of the mass when they took control. At a subsequent congress of the soviets the Bolsheviks had 390 out of a total of 676. It is worthy of note that none of the capitalist papers gave any description of the method of electing either the Soviets or the delegates to the Congress. And still more curious is it that though M. Litvinoff says these delegates “were elected on a most democratic basis”, he does not give the slightest information about this election. This is more significant as he claims the Constituent Assembly “had not faithfully represented the real mind of the people”.

From the various accounts and of the capitalist Press (and, as stated above, M. Litvinoff does not supply us with any other information) it seem the Bolsheviks form the driving force, and perhaps even the majority, of the new Government, sometimes called the Soviet Government and sometimes the “Council of Peoples’ Commissaries”. The Soviet Government certainly appears to have been accepted, or at least acquiesced in, by the bulk of the Russian workers. The grounds for this acceptance are fairly clear. First the Soviet Government promised peace; secondly they promised a settlement of the land question; thirdly they announced a solution of the industrial workers grievances. Unfortunately various and often contradictory accounts are given of the details of this programme, and Litvinoff’s statements are in vague general terms that give no definite information on the matter. Until some reliable account of the Soviet Government’s programme is available detailed judgement must remain suspended. That this mixed Government should have been tacitly accepted by the Russian workers is no cause for surprise. Quite the contrary. They (the Soviet Government) appear to have done all that was possible in the circumstances to carry their peace proposals. And we are quite confident that if the mass of the people in any of the belligerent countries, with the possible exception of America, were able to express their views, free from consequences, on Peace or Continuance of War, an overwhelming majority would declare in favour of Peace.

As is admitted by the various sections of the capitalist Press, the Soviet representatives at the Brest-Litovsk Conference stood firm on their original proposals to the last moment. That they had to accept hard terms in the end is no way any discredit to them, but it was a result of conditions quite beyond their control. If they had done no more than this, if they had been compelled to give up office on their return, the fact that they had negotiated a stoppage of the slaughter and maiming of millions of the working class would have been a monument to their honour, and constituted an undeniable claim to the highest approbation of the workers the world over.

Of course the capitalist Press at once denounced the signing of the Peace treaty as “dastardly treachery”, and so on. We can quite easily understand that the agents of the foullest and most hypocritical ruling class the world has ever seen, steeped to their eyes in their own cruel treacheries, should have been astounded at the Soviet Government keeping its pledge to the Russian people, instead of selling them out to the Allied Governments.

Then follow the usual stereotyped “outrages” and “crimes” that the master class agents never fail to provide when an opponent dares to stand in their path. Unfortunately for these capitalist agents, their own correspondents are allowed to move freely over the country, and often “give the game away” by describing improvements both in ordinary administration and economic conditions under the new rule. And Mr. Litvinoff scores neatly here over the capitalist Press by comparing the alleged “outrages” with the actions of the master class against the workers after the fall of the Paris commune. A still more striking illustration is given by the Mr. Price from Russia itself, in his article in the Manchester Guardian for November 28th , 1917, where he describes the cold-blooded slaughter of 500,000 Khirgiz Tartars by the Czar’s Government in 1916. And he caustically remarks:

“While Western Europe has heard about Armenian massacres, the massacre of the Central Asian Moslems by the Tsar’s agents has been studiously hidden.”

Indeed, if the Soviet Government were to start on a campaign of deliberate slaughter, it would take them many busy years to even approach the huge number of victims of the last Czar’s reign. But so far all the evidence points to the allegations of Bolshevik butcheries being but a tissue of lies fabricated to suit bourgeois purposes.

And what of the future? It is impossible to offer any close forecast in the face of our lack of knowledge. We do not know what the Soviet Government has promised the peasants. We are ignorant of what measures they are putting into operation to solve the complicated land question. Despite the existence of the Mir organisation it will be easier for the Russian government to arrange for the management of the factories and industries of the towns than to settle the various and widely divergent, detailed demands of the peasants of the different provinces. There is no ground whatever for supposing that they are ready or willing to accept social ownership of the land, along with the other means of production. Are the Bolsheviks prepared to try to establish something other than this? If so does it not at once flatly contradict M. Litvinoff’s claim that they are establishing Socialism?

And grim shadows are spreading from both sides. On one side the Germans are trying to exploit and plunder as much as possible why they have the chance; on the other side the Japanese, assisted by British and American forces are entering on an exactly similar expedition, with the same objects in view. Also it has been reported that the Allied forces landing on the Murman coast are either under the command of or are accompanied by a notorious Czarist officer, General Gourko, who is working hard for the restoration of the Romanoffs.

With the mass of the Russian people still lacking the knowledge necessary for the establishment of socialism, with both groups of belligerents sending armed forces into the country, with the possible combination of those groups for the purpose of restoring capitalist rule, even if not a monarchy, in Russia, matters look gloomy for the people there. If the capitalist class in the belligerent countries succeed in this plan, the Soviet Government and its supporters may expect as little mercy as—nay, less than—the Khirgiz Tartars received. It may be another Paris Commune on an immensely larger scale.

Every worker who understands his class position will hope that some way will be found out of the threatened evil. Should that hope be unrealised, should further victims be fated to fall to the greed and hatred of the capitalist class, it will remain on record that when members of the working class took control of affairs in Russia, they conducted themselves with vastly greater humanity, managed social and economic matters with greater ability and success and with largely reduced pain and suffering, than any section of the cunning, cowardly, ignorant capitalist class were able to do, with all the numerous advantages they possessed.

(Socialist Standard, August 1918)

************************************************************

5) A Socialist View of Bolshevik Policy

(July 1920)

Where We Stand

Ever since the Bolshevik minority seized the control of affairs in Russia we have been told that their “success” had completely changed Socialist policy. These “Communists” declare that the policy of Marx and Engels is out of date. Lenin and Trotsky are worshipped as the pathfinders of a shorter and easier road to Communism.

Unfortunately for these “Bolsheviks,” no evidence has yet been supplied to show wherein the policy of Marx and Engels is no longer useful, and until that evidence comes the Socialist Party of Great Britain will continue to advocate the same Marxian policy as before. We will continue to expose and oppose the present system and all its defenders and apologists. We shall insist upon the necessity of the working class understanding Socialism and organising with a political party to obtain it.

Socialism Far Off in Russia

When we are told that Socialism has been obtained in Russia without the long, hard and tedious work of educating the mass of workers in Socialism we not only deny it but refer our critics to Lenin’s own confessions. His statements prove that even though a vigorous and small minority may be able to seize power for a time, they can only hold it by modifying their plans to suit the ignorant majority. The minority in power in an economically backward country are forced to adapt their program to the undeveloped conditions and make continual concessions to the capitalist world around them. Offers to pay war debts to the Allies, to establish a Constituent Assembly, to compensate capitalists for losses, to cease propaganda in other countries, and to grant exploitation rights throughout Russia to the Western capitalists all show how far along the capitalist road they have had to travel and how badly they need the economic help of other countries. It shows above all that their loud and defiant challenge to the capitalist world has been silenced by their own internal and external weaknesses as we have so often predicted in these pages.

Lenin’s Confessions

The folly of adopting Bolshevik methods here is admitted by Lenin in his pamphlet The Chief Tasks of Our Times (p. 10). “A backward country can revolt quicker, because its opponent is rotten to the core, its middle class is not organised; but in order to continue the revolution a backward country will require immediately more circumspection, prudence, and endurance. In Western Europe it will be quite different; there it is much more difficult to begin, but it will be much easier to go on. This cannot be otherwise because there the proletariat is better organised and more closely united.”

Those who say “Russia can fight the world”, are answered by Lenin:

“Only a madman can imagine that the task of dethroning International Imperialism can be fulfilled by Russia alone.”

Lenin admits that “France and England have been learning for centuries what we have only learnt since 1905. Every class-conscious worker knows that the revolution grows but slowly amongst the free institutions of a united bourgeoisie, and that we shall only be able to fight against such forces when we are able to do so in conjunction with the revolutionary proletariat of Germany, France, and England. Till then, sad and contrary to revolutionary traditions as it may be, our only possible policy is to wait, to tack, and to retreat.”

State Capitalism for Russia

We have often stated that because of a large anti-Socialist peasantry and vast untrained population, Russia was a long way from Socialism. Lenin has now to admit this by saying: “Reality says that State Capitalism would be a step forward for us; if we were able to bring about State Capitalism in a short time it would be a victory for us. How could they be so blind as not to see that our enemy is the small capitalist, the small owner? How could they see the chief enemy in State Capitalism? In the transition period from Capitalism to Socialism our chief enemy is the small bourgeoisie, with its economic customs, habits and position” (p. 11).

This reply of Lenin to the Communists of the Left (Bucharin and others) contains the further statement that, “To bring about State Capitalism at the present time means to establish the control and order formerly achieved by the propertied classes. We have in Germany an example of State Capitalism, and we know she proved our superior. If you would only give a little thought to what the security of such State Socialism would mean in Russia, a Soviet Russia, you would recognise that only madmen whose heads are full of formulas and doctrines can deny that State Socialism is our salvation. If we possessed it in Russia the transition to complete Socialism would be easy, because State Socialism is centralisation control, socialisation—in fact, everything that we lack. The greatest menace to us is the small bourgeoisie, which, owing to the history and economics of Russia, is the best organised class, and which prevents us from taking the step, on which depends the success of Socialism.”

Here we have plain admissions of the unripeness of the great mass of Russian people for Socialism and the small scale of Russian production.

If we are to copy Bolshevist policy in other countries we should have to demand State Capitalism, which is not a step to Socialism in advanced capitalist countries. The fact remains, as Lenin is driven to confess, that we do not have to learn from Russia, but Russia has to learn from lands where large scale production is dominant.

Lenin and the Trusts

“My statement that in order to properly understand one’s task one should learn socialism from the promoters of Trusts aroused the indignation of the Communists of the Left. Yes, we do not want to teach the Trusts; on the contrary, we want to learn from them.” (p. 12) Thus Lenin speaks to his critics. Owing to the untrained character of the workers and their failure to grasp the necessity of discipline and order in large scale production, Lenin has to employ “capitalist” experts to run the factories. He tells us: “We know all about Socialism, but we do not know how to organise on a large scale, how to manage distribution, and so on. The old Bolshevik leaders have not taught us these things, sand this is not to the credit of our party. We have yet to go through this course and we say: Even if a man is a scoundrel of the deepest dye, if he is a merchant, experienced in organising production and distribution on a large scale, we must learn from him; if we do not learn from these people we shall never achieve Socialism, and the revolution will never get beyond the present stage. Socialism can only be reached by the development of State Capitalism the careful organisation of finance, control and discipline among the workers. Without this there is no Socialism.” (p. 12.)

That Socialism can only be reached through State Capitalism is untrue. Socialism depends upon large-scale production, whether organised by Trusts or Governments. State capitalism may be the method used in Russia, but only because the Bolshevik Government find their theories of doing without capitalist development unworkable—hence they are forced to retreat along the capitalist road.

The Internal Conflict

Lenin goes on: “The workers who base their activities on the principles of State Socialism are the most successful. It is so in the tanning, textile, and sugar industries, where the workers, knowing their industry, and wishing to preserve and to develop it, recognise with proletarian common sense that they are unable at present to cope with such a task, and therefore allot one third of the places to the capitalists in order to learn from them.”

This concession is another example of the conflict between Bolshevik theory and practice, for the very argument of Lenin against Kautsky and others was that in Russia they could go right ahead without needing the capitalist development such as it exists in other countries.

The whole speech of Lenin is directed against the growing body of workers in Russia who took Lenin at his word. These people fondly imagined that after throwing over Kerensky they could usher in freedom and ignore the capitalist world around them. They thought that factory discipline, Socialist education, and intelligent skilled supervision were simply pedantic ideas.

A further quotation from Lenin will make this clear: “Naturally the difficulties of organisation are enormous, but I do not see the least reason for despair and despondency in the fact that the Russian Revolution, having first solved the easier task—the overthrow of the landowners and the bourgeoisie, is now faced with the more difficult Socialist task of organising national finance and control, a task which is the initial stage of Socialism, and is inevitable, as is fully understood by the majority of class-conscious workers.”

He also says: “It is time to remonstrate when some people have worked themselves up to a state in which they consider the introduction of discipline into the ranks of the workers as a step backwards.” And he points out that “by the overthrow of the bourgeoisie and landowners we have cleared the way, we have not erected the structure of Socialism.”

How far they have cleared the capitalists out of the way is uncertain, as they are a long way from self-reliance. The long road ahead is admitted by Lenin in these words: “Until the workers have learned to organise on a large scale they are not Socialists, nor builders of a Socialist structure of society, and will not acquire the necessary knowledge for the establishment of the new world order. The path of organisation is a long one, and the tasks of Socialist constructive work require strenuous and continuous effort, with a corresponding knowledge which we do not sufficiently possess. It is hardly to be expected that the even more developed following generation will accomplish a complete transition into Socialism.” (p. 13.)

The Rule of the Minority

The denunciation of democracy by the Bolshevik leaders is quite understandable if we realise that only the minority in Russia are Communists. Lenin therefore denies control of affairs to the majority, but he cannot escape from the compromise involved in ruling with a minority. Not only is control of Russian affairs out of the hands of the Soviets as a whole, but not even all the members of the Communist Party are allowed to vote. Zinoviev, a leading Commissar, in his report to the First Congress of the Third International said:

“Our Central Committee has decided to deprive certain categories of party members of the right to vote at the Congress of the party. Certainly it is unheard of to limit the right voting within the party, but the entire party has approved this measure, which is to assure the homogenous unity of the Communists So that in fact, we have 500,000 members who manage the entire State machine from top to bottom.” (The Socialist, 29.4.20. Italics not ours.)

So half a million members of the Communist Party (counting even those who are refused a vote within the party) control a society of 180 million members. It is quite plain why other parties’ papers were suppressed: obviously they could influence the great majority outside the Communist Party. The maintenance of power was assured by the Bolshevik minority through its control of political power and the armed forces.

************************************************************

6) The Super Opportunists

(August 1920)

A Fatuous Policy

The Bolshevik leaders are opportunists. They start out with a definite programme and policy but change it completely when they find the world’s workers do not support them. Lenin, Trotsky, Radek, and the other officials denounced Kautsky, Henderson, Longuet, and others for their reformist policy, but we now have Lenin and Zinoviev advising the Socialist workers of England to take parliamentary action and join the Labour Party.

The report of the Executive of the Communist Party of Russia to the 1920 congress of the Third International lays down the position that we should get inside the Parliamentary Labour parties. This advice is anti-Socialist, as anybody with a knowledge of the history and composition of the Labour parties know.

The Bolshevik leaders told us that the workers of the world were ripe for revolution and their support of Bolshevism was expected and depended upon. Now that it is plain that workers do not understand socialism and fight for it, Lenin is pandering to the ignorance of the world’s workers. In defence he says that by supporting the pro-capitalist Labour Party and helping to establish a Labour Party government, the workers will learn the uselessness of the Labour parties.

The Logical Conclusion

If that policy is to be adopted, then it is necessary for the workers to follow every false road, to support every reactionary measure, and to join every movement and learn from their mistakes—in other words, exhaust every possible evil before they try the right road. If this policy is right why did not Lenin support Kerensky’s policy of capitalism for Russia and let the workers painfully learn its uselessness? Such nonsense as supporting parties and Governments to gain power to learn their misdeeds is not the road to Socialism, it is the path to apathy and despair, and lengthens capitalism’s life.

The Opportunist Weathercocks

After spending much ink and eloquence in denouncing parliamentary action Lenin tells us in his interview in the Manchester Guardian that it is necessary in modern capitalist countries.

In his telegram to the British Socialist Party Lenin calls upon them to support parliamentary action by means of a Labour party. After all the attempts of Lenin to show that Marx and Engels believed in smashing the State power, Trotsky tells us in A Paradise for the Workers that we have to get control of the State power and use it instead of abolishing it. Radek, in his Communism—From Science to Action, denounced parliamentary action and majority rule, but in a recent letter to a German Communist he completely changes round and advises parliamentary action.

Lenin, in his letter to the German party, supports Parliamentary Action and the winning of the masses in defiance of all his previous advice and previous praise of the Spartacan minority action. The Amsterdam Bureau of the Third International was abolished because it told the English Socialists not to engage in Parliamentary Action or to support the Labour Party. All this demonstrates the absence of any principle and simply to veer with the changing winds.

We have been denounced for our attitude of insisting upon the need of Socialists making a revolutionary use of parliaments. Our position, however, was based upon Socialist principles and a recognition of the facts of history, not a desire to pander to popular prejudices such as support of a dangerous and fraudulent Labour party.

We have opposed Kautsky’s reformism and opportunism because it is not Socialism and is against the principle of the Class Struggle. We are equally opposed to dangerous teachings if they come from Lenin, Radek, or any other man who sets himself up as a teacher of socialism. Our position is that taken up by Marx and Engels and made plain by them in their writings. Engels says in his last (1890) preface to the Communist Manifesto that we must gain the minds of the masses. Bolshevism, however, has depended for its triumph upon the minority, who ignored the majority of workers. So true is this that Radek in his pamphlet ridicules anything else in minority action for Socialism.

Bertrand Russell, who accompanied the Labour delegation to Russia in June, records his interview with Lenin in the Nation (July 10th and 17th), and Lenin there admits the opposition of the peasantry. Lenin in reply to Kautsky (The Dictatorship and the Betrayer Kautsky) does not attempt to deny Kautsky’s charge that the Menshevik and Social-Revolutionary delegates to the Soviets were suppressed in order to maintain Bolshevik majorities. Russell states the Soviets are moribund and that any other delegates than Bolshevik ones are denied railway passes and so cannot attend the Soviet meetings. He also says that the All Russian Soviet meets seldom, that the recall is exercised for minor offences, such as drunkenness, and that the delegates continually ignore their constituents. We do not accept Russell as an authority, but much of his report agrees with Bolshevik writings.

We have always contended that the Bolsheviks could only maintain power by resorting to capitalist devices. History has shown us to be correct. The January 1920 Congress of the Executive Communists in Russia abolished the power of workers control in factories and installed officials instructed by Moscow and given controlling influence. Their resolutions printed in most of the Labour papers and the Manchester Guardian here show how economic backwardness has produced industrial conscription with heavy penalties for unpunctuality, etc. The abolition of democracy in the army was decreed long ago, but now that the army is being converted into a labour army it means rule from the top with an iron hand.

Russia has agreed to repay foreign property-owners their losses and allied Governments their “debts.” This means continued exploitation of Russian workers to pay foreign exploiters.

With all the enthusiasm of the Communists they find themselves faced with the actual conditions in Russia and the ignorance of the greater part of its population.

There is no easier road to Socialism than the education of the workers in Socialism and their organisation to establish it by democratic methods. Russia has to learn that.

************************************************************

7) The Passing of Lenin

(March 1924)

One of the significant facts brought into prominence by the great war was the intellectual bankruptcy of the ruling class of the Western World. A gigantic field of operations and colossal wealth at their disposal, failed to bring out a single personality above the mediocre, from England and Germany down the list to America and Roumania. The only character that stood, and stands, above the Capitalist mediocrities, was the man lately buried in Moscow – Nikolai Lenin.

The senseless shrieks of the Capitalist henchman against Lenin was itself evidence of their recognition of their own inferiority. All the wild and confused tales that were told by the agents of the master class (from Winston Churchill to Mrs. Snowden) to suggest that Lenin was “the greatest monster of iniquity the world has ever seen,” largely defeated their object, to every person capable of thinking clearly, by their sheer stupidity and extravagance.

One result of this tornado of lies was to cause a corresponding reaction on the other side. The various groups of woolly headed Communists, inside and outside of Russia, began to hail Lenin a new “Messiah” who was going to show the working class a new quick road to salvation. Thus does senseless abuse beget equally senseless hero-worship

From sheer exhaustion the two-fold campaign has died down in the last year or two, even the “stunt” press only giving small space to Lenin and Russia.

Lenin’s sudden death, despite his long illness, has brought forward a flood of articles and reviews entirely different in tone from those that greeted his rise to power.

The shining light of modern Conservatism – Mr. J. L. Garvin – does not know whether Lenin was famous or infamous, whether he was a great man or a great scoundrel, so, wisely, leaves the verdict to posterity to settle.

A Fabian pet, Mr. G. D. H. Cole, in the New Statesman, for the 2nd February, makes the claim that Lenin’s great work was the “invention of the Soviet”! It is difficult to understand how the editor of a journal, supposed to be written for “educated” people, should have allowed such a piece of stupid ignorance to have passed his scrutiny. The word “Soviet” – that seems to have mesmerised some people – simply means “Council.” Every student of Russia knows that the “Council” has been an organic part of the Russian Constitution since the middle of the 16th century. But there may be another explanation of Mr. Cole’s attitude. As one of the leaders of that hopeless crusade to turn back the hands of the clock (known as “The Guild System”) he sees around him the ruins and the rubbish of the various experiments in this system and maybe he hopes by claiming Russia as an example of “Guildism” to arouse some new enthusiasm for further useless experiments. His hopes are built on shifting sands.

Michael Farbman, in the Observer, Jan. 27th, 1924, takes a more daring and dangerous line. He claims to understand Marx and Marxism, and yet makes such statements as:-

“When Lenin inaugurated the Dictatorship of the Proletariat he obviously was unhampered by the slightest hesitation or doubt as to the efficacy of Marxian principles. But the longer he tested them as a practical revolutionist and statesman the more he became aware of the impossibility of building up a society on an automatic and exclusively economic basis. When he had to adopt an agrarian policy totally at variance with his Marxian opinions, and when later he was compelled to make an appeal to the peasants’ acquisitive instincts and go back to what he styled ‘State Capitalism,’ he was not only conscious that something was wrong with his Marxian gospel, but frankly admitted that Marx had not foreseen all the realities of a complex situation. It is probably no exaggeration to say that the greatest value of the Russian Revolution to the world Labour movement lies in the fact that it has replaced Marxism by Leninism.”

The above quotation has been given at length because it not only epitomises Mr. Farbman’s attitude but also that of many so-called “Socialists.”

It will, therefore, be a matter of astonishment to the reader unacquainted with Marx’s writings and theories to learn that almost every sentence in that paragraph either begs the question or is directly false.

In the first sentence we have two assertions, One that Lenin established the “ Dictatorship of the Proletariat,” the other that this is a “Marxian principle.” Both statements are deliberately false.

Lenin never established any “Dictatorship of the Proletariat” – whatever that may mean – but only the Dictatorship of the Communist Party which exists today. In the whole of Marx’s writing that he himself saw through the press the phrase Dictatorship of the Proletariat does not occur once! This, of course, Mr. Farbman knows well.

The next sentence contains a phrase that Mr. Farbman may know the meaning of, but which is idiotic nonsense from a Marxian standpoint. To talk of a Society “on an automatic and exclusively economic basis” is utterly in opposition to all Marxian teachings.

If Lenin ever made the statement attributed to him in the sentence that follows – “that Marx had not foreseen all the realities of a complex situation” – which is at least doubtful as no reference is given, that would only show Lenin’s misreading of Marx.

But the last sentence is a gem. Not only has the Russian revolution not displaced Marxism by Leninism (for as showed above Marxism never existed there) – it has displaced Leninism by Capitalism.

To understand Lenin’s position, both actually and historically, it is necessary to examine the conditions under which he came to the front. Early in 1917 it was clear to all observers that the corruption, treachery and double-dealing of the Czar and his nobles had brought about the collapse of the Army. (See M, Phillips Price The Soviet, the Terror and Intervention, p. 15; John Reed, Ten Days that Shook the World, etc,).

This was the most important factor in the whole Russian upheaval, and is the pivot upon which all the rest turns.

The Romanoffs and their crew had fallen from power when an efficient armed force was no longer at their disposal. Kerensky, who replaced them, tried to keep the war going without men or munitions. Lenin obtained permission to leave Switzerland for Russia and tried to stir up a revolt in March, 1917, but this failed, and he had to fly to Finland. Confusion grew, and finally it was decided to take steps to call a Constituent Assembly to draw up a new Constitution for Russia. The Bolsheviks hailed this move and loudly protested against the dilatoriness of Kerensky, who was afraid of losing office. At the same time the various Councils of peasants, workers and soldiers began to send representatives to Petrograd for an All-Russian Congress. At once a struggle began between the Kerensky section – or Mensheviks – and the Lenin section – or Bolsheviks – to obtain the majority of representation in this Assembly. For days the struggle continued and almost to the last moment the issue was in doubt, but the superior slogan of the Bolsheviks – “Peace, Bread, Land” – finally won a majority over to their side.

A day or two before this Lenin had come out of his hiding place and placed himself at the head of the Bolsheviks.

The first thing Lenin did when in office was to keep his promise. He issued a call for peace to all the belligerents on the basis of’ “no annexations, no indemnities.” This astonished the politicians of the Western Nations to whom election promises are standing jokes.

It was at this point that Lenin made his greatest miscalculation. He believed that the working masses of the western world were so war weary that upon the call from one of the combatants they would rise and force their various Governments to negotiate peace. Unfortunately these masses had neither the knowledge nor the organisation necessary for such a movement, and no response was given to the call, except the snarling demands of the Allies that Russia should continue to send men to be slaughtered. This lack of response was a terrible disappointment to Lenin, but, facing the situation, he opened negotiations for a separate peace with Germany. And here he made a brilliant stroke. To the horror and dismay of all the diplomatic circles in Europe he declared that the negotiations would be carried on in public, and they were. Thus exposing the stupid superstition still so beloved of Communists here, that it is impossible to conduct important negotiations in public.

Of course the conditions demanded by the Germans were hard. Again and again Lenin’s followers demanded that war should be re-opened rather than accept these conditions. Radek reports a conversation (Russian Information and Review, January 26th, 1924):-

“The mujik must carryon the war. ‘But don’t you see that the mujik voted against the war,’ Lenin answered. ‘Excuse me, when and how did he vote against it?’ ‘He voted with his feet; he is running away from the front.’”

Large tracts of territory were detached from the Bolshevik control, and the greatest blow was the separation of the Ukraine, whose splendid fertile soil would have been of immense value for the purpose of providing food.

Still the problems to be handled were enormous. The delegates to the Constituent Assembly had gathered in Petrograd, but Lenin, who shouted so loudly for this Assembly when out of office, was not running the risk of being deposed now he was in office. He had the gathering dispersed, and refused to let the Assembly meet. Sporadic outbreaks among the peasantry were a source of continual trouble, particularly as the Bolsheviks had only a poor force at their disposal. The signing of the Armistice however solved this problem. The Communists are fond of claiming that Trotsky organised the “Red Army.” This claim is absurd, for Trotsky knew nothing of military matters. The upheaval in Germany, after the signing of the Armistice, threw hundreds of German officers out of work and Lenin gladly engaged their services, at high salaries, to organise the army. By the offer of better food rations, better clothing and warmer quarters plenty of men offered themselves for enlistment. The main difficulty however was not men but munitions.

Lenin and his supporters expected that the victorious Allies would turn their combined forces on Russia. But the Allies were so engrossed in trickery, double-dealing and swindling each other over the sharing of the plunder that they largely ignored Russia. Still to show their good will and kind intentions they subsidised a set of thieving scoundrels – Koltchak (assisted by that British hero “Colonel” John Ward), Deniken, Wrangel, Yudenitch, etc., to invade Russia for the purpose of taking it out of the control of the Russians.

It was a most hopeful undertaking, this sending in of marauding bands! The peasant, who had just got rid of his age-long enemy the landlord (sometimes rather summarily) was expected to assist in restoring that gentleman. To help them in reaching a decision, these marauding bands, with strict impartiality, plundered friend and foe alike. The only result of these various raids was to unify the mass of the people in Russia in accepting the Bolshevik rule. Slowly the Russians began to gather arms. Their army was already in good order, and although the enormous distances and lack of transport prevented them reaching many places, yet whenever the Red Army met the looting bands mentioned above the latter were defeated, with monotonous regularity.

Of course compared with the battles on the western front these engagements were mere hand skirmishes, as neither side had any heavy artillery, high-velocity shells, poison gas, nor bombing aeroplanes.

A greater enemy to Leninism than any of these gangs, however, and one which had been exerting its influence for some time, now greatly increased its pressure, this was the individualistic conditions of the peasant, combined with the wants of the townsmen. Various decrees had been passed forbidding private trading in the towns and villages (apart from special licences) but the Bolsheviks had never dared to enforce these decrees in face of the food shortage. The result of this increased pressure was the famous “New Economic Policy,” that caused such consternation in the ranks of the Communist parties. In this country Miss Sylvia Pankhurst nearly died of disgust when the news arrived.

But once more Lenin was right. He recognised the seriousness of the conditions and tried to frame a policy to fit them. His own words describe the situation with great clearness:-

“Yet, in 1921, after having emerged victoriously from the most important stages of the Civil War, Soviet Russia came face to face with a great – I believe, the greatest – internal political crisis which caused dissatisfaction, not only of the huge masses of the peasantry, but also of large numbers of workers.

“It was the first, and I hope the last, time in the history of Soviet Russia that we had the great masses of the peasantry arrayed against us, not consciously, but instinctively, as a sort of political mood.

“What was the cause of this unique, and, for us, naturally disagreeable, situation? It was caused by the fact that we had gone too far with our economic measures, that the masses were already sensing what we had not properly formulated, although we had to acknowledge a few weeks afterwards, namely, that the direct transition to pure Socialist economy, to pure Socialistic distribution of wealth, was far beyond our resources, and that if we could not make a successful and timely retreat, if we could not confine ourselves to easier tasks, we would go under.” (Address to the Fourth Congress of the Communist International.) (Italics ours.)

The most significant phrase in the above statement – the one we have underlined – now admits at last that Marx was right, and that the whole of the Communist “Theories and Theses” are rubbish from top to bottom.

Mr. Brailsford, the £1,000 a year, editor of The New Leader, in the issue for January 25th, 1924 says:-

“Alone in the earthquakes of the war period, this Russian revived the heroic age, and proved what the naked will of one man may do to change the course of history.”

What knowledge! What judgement! What intelligence! Where has the “course of history” changed one hair’s breadth owing to Russia? And the above specimen of ignorance, that would disgrace a school child, is considered worth £1,000 a year by the I.L.P.! Doubtless the measure of their intelligence.

The chief points of Lenin’s rule can now be traced out. He was the product of the “course of history” when the breakdown occurred in Russia. At first – nay even as late as the publication of Left-Wing Communism (p.44) – Lenin claimed that it was “a Socialist Revolution.” He also claimed that the Bolsheviks were establishing “Socialism” in Russia in accord with Marxian principles. Some of the shifts, and even deliberate misinterpretations of Marx’s writings that Lenin indulged in to defend his unsound position have already been dealt with in past issues of the SOCIALIST STANDARD and need not detain us here. To delay the victorious Allies taking action against Russia, large sums were spent on propaganda in Europe by the Bolsheviks. “Communist” Parties sprang up like mushrooms, and now that these funds are vanishing, are dying like the same vegetable. Their policy was to stir up strife. Every strike was hailed as the “starting of the revolution.” But somehow they were all “bad starts”!

When the Constituent Assembly was broken up by Lenin’s orders he had the Russian Soviet Constitution drawn up. He realised that if the Bolsheviks were to retain control this new Constitution must give them full power. We have already analysed this Constitution in detail, in a previous issue, but a repetition of one point will make the essential feature clear. Clause 12 says:-

“The supreme authority in the Russian Soviet Republic is vested in the All Russia Congress of Soviets, and, during the time between the Congresses, in the Central Executive Committee.”

Clause 28 says:-

“The All Russia Congress of Soviets elects the All Russia Central Executive of not more than 200 members.”

Innocent enough, surely! But – yes there is a but – the credentials of the delegates to the All-Russia Congress are verified by the officials of the Communist Party and at every congress it turns out – quite by accident of course – that a large majority of the delegates are members of the Communist Party. The others are listened to politely, allowed to make long speeches, and then voted down by the “Block.” This little fact also applies to all “The Third Communist International Congresses,” and to all “The International Congresses of the Red Labour Unions.” No matter how many delegates the other countries may send, the Russian delegation is always larger than the rest combined.

By this “Dictatorship of the Communist Party” Lenin was able to keep power concentrated in his own hands.

Lenin made desperate efforts to induce the town workers to run the factories on disciplined lines, but despite the most rigid decrees these efforts were a failure. The Russian townsmen, like the peasant, has no appreciation of the value of time, and it is impossible to convert a 17th century hand worker into a modern industrial wage slave by merely pushing him into a factory and giving him a machine to attend. Lenin’s experience proves the fallacy of those who proclaim that modern machines, because they are made “fool-proof” in some details, can be operated by any people, no matter how low their stage of development.

Another idea was tried. A number of minor vultures on the working class, of the I.W.W. and Anarchist “leader” type, had gone to Russia to see what could be picked up. There were 6,000,000 unemployed in America. Lenin called upon these “leaders” to arrange for the transport of numbers of mechanics and skilled labourers to form colonies in Russia, with up-to-date factories and modern machinery. These “leaders” pocketed their fees and expenses, but the colonies have yet to materialise.

Such was the position up to the time of Lenin’s illness.

What then are Lenin’s merits? First in order of time is the fact that he made a clarion call for a world peace. When that failed he concluded a peace for his own country. Upon this first necessary factor he established a Constitution to give him control and, with a skill and judgement unequalled by any European or American statesman, he guided Russia out of its appalling chaos into a position where the services are operating fairly for such an undeveloped country, and where, at least, hunger no longer hangs over the people’s heads. Compare this with the present conditions in Eastern Europe!

Despite his claims at the beginning, he was the first to see the trend of conditions and adapt himself to these conditions. So far was he from “changing the course of history” as Brailsford ignorantly remarks that it was the course of history which changed him, drove him from one point after another till today Russia stands halfway on the road to capitalism. The Communists, in their ignorance, may howl at this, but Russia cannot escape her destiny. As Marx says:-

“One nation can and should learn from others. And even when a society has got upon the right track for the discovery of the natural laws of its movement – and it is the ultimate aim of this work to lay bare the economic law of motion of modern society – it can neither clear by bold leaps nor remove by legal enactments the obstacles offered by the successive phases of its normal development. But it can shorten and lessen the birth pangs.” (Preface Vol, I. Capital.)

The Bolsheviks will probably remain in control for the simple reason that there is no one in Russia capable of taking their place. It will be a question largely as to whether they will be able to stand the strain for the task is a heavy one, and they are by no means overcrowded with capable men. But this control will actually resolve itself into control for, and in the interests of, the Capitalists who are willing to take up the development of raw materials and industry in Russia. The New Economic Policy points the way.

The peasant problem will take longer to solve because of the immense areas, and lack of means of communication. Until the capitalists develop roads and railways the peasants will, in the main, follow their present methods and habits. When these roads and railways are developed, modern agriculture will begin to appear worked at first with imported men and machines. But then Russia will be well on the road to fully developed Capitalism.

The Communists claim that Lenin was a great teacher to the working class the world over, but with singular wisdom they refrain from pointing out what that teaching was. His actions from 1917 to 1922 certainly illustrate a certain lesson that is given above, but the teacher of that lesson was Karl Marx.

(April 1924)

************************************************************

8) Trotsky states His Case

(December 1928)

(The Real Situation in Russia, by Leon Trotsky. Translated by Max Eastman. 364 pages. 7s. 6d. George Alien & Unwin.)

This book consists for the most part of the statement submitted by Trotsky (and 12 other minority members) to the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party in September, 1927. The document was suppressed by Stalin and his supporters, and the opposition group—both in the Central Committee and in the country at large—was broken up by the imprisonment, persecution and exile of its prominent members. As might have been expected a copy of the statement was smuggled out of Russia, and now appears in an English edition. It is translated by Max Eastman, who is an American admirer of Trotsky, and was himself recently in Russia.

Trotsky describes in considerable detail the serious problems which face the workers in Russia under Stalin’s Government, the charges which his group level at the dominant section in the Communist Party, and the remedies which they propose.

The richer peasants in the country, and the trading and money lending capitalists in the towns are increasing in wealth and are becoming a more powerful factor politically. One-fifth of all trade, 50 per cent, of retail trade and more than 20 per cent, of industrial production is in private hands (page 27). The profits of the trading capitalists, the middle men, are big and growing while the workers’ share in the national income has been falling since 1925. The introduction of methods of rationalisation into State industry results in an increase of unemployment, a general intensification of labour, and a lowered standard of living.

The fear of unemployment is such that the workers resist the efforts of the Government to increase production in the factories by machinery and more efficient methods.

Among the 3½ million rural wage workers the rates of pay are often below the legal minimum even on the Soviet State farms. Housing for the town workers grows steadily worse.

Workers’ control is more than ever a mere catch-word without real application. “Never before have the trade unions and the working mass stood so far from the management of the Socialist industry as now” (page 57).

The immense majority of delegates to Trade Union Conferences are people entirely dissociated from actual participation in industry. Factory committees are mistrusted and discontent is driven underground because the man who voices a complaint knows that he will lose his job. Men and women are not equally paid.

Capitalism on the land

During the previous four years Trotsky alleges that from 35 per cent, to 45 per cent, of the landless rural workers and small peasants were unable to continue making a living, while the rich class of peasants (more than 28 acres) increased in number by from 150 per cent. to 200 per cent. (p. 61). In a typical district 15 per cent. of the peasants own 50 per cent. of the land machinery, cattle, etc. Renting of land is on the increase, and the army of landless rural labourers is continually being recruited from the poor peasantry.

The new bureaucracy

Under Bolshevik administration there has grown up a new bureaucracy, divorced from working class life and not subject to any effective control from below. “The city Soviets have been losing in these recent years all real significance.” “The Soviets are having continually less and less to do with the decision of fundamental, political, economic, and cultural questions. They are becoming mere supplements to the executive committees and the praesidiums. . . . The discussion of problems at the full meeting of the Soviets is a mere show discussion” (pages 98 and 99). Elected delegates are promptly removed from office if they express on behalf of the workers any criticism of the official element.

The composition of the Communist Party is deteriorating. At the beginning of 1927 only one-third of the members were shop and factory workers, while two-thirds were peasants, officials, etc. In 18 months over 100,000 industrial workers were lost to membership and an equal number of peasants admitted. The majority of these were “middle” peasants, the percentage of farm labourers being insignificant.

Inside the Communist Party “the genuine election of officials is in actual practice dying out” (page 115). Terms of office are being increased to two or more years. The Party machinery is used to secure the dismissal from their employment of workers who criticise the leadership.

Communist Party groupings

There are, in Trotsky’s analysis, three main groups. First, a right wing group, which combines the aims of the middle peasants with those of the Trade Union leaders and the better paid clerical and other workers. Secondly, there is the ruling section of the Communist Party, the members of the Government and the administration. Their object is to avoid if possible any change in the present balance of forces such as will disturb their own position.

And, thirdly, there is the Trotsky group, which claims to represent the mass of the industrial workers.

Lenin worship

Quite a large part of the book is given up to the personal issues between Trotsky and the members of the Government. Each section and all of the individual disputants try desperately hard to prove not only that their views are in accord with Lenin’s general line of policy, but that during his lifetime they possessed Lenin’s personal regard. These personal issues may be of interest to the English reader, but are not of great importance. They are, however, significant in that they indicate what both Stalin’s group and Trotsky’s group think of the degree of understanding possessed by the members of the Communist Party in Russia. Whatever may be the real opinion of Stalin and Trotsky as to the value of this “Lenin worship” and controversies about personal merits (it is noteworthy that Trotsky specifically credits Stalin’s faction with “sincerity,” p. 185), they both plainly realise that in the life and death struggle which involves the political careers and the very existence of the oppositionists, they have got to canvass support by “arguments” based on abuse and on the kind of trivialities which are the stock in trade of every demagogue appealing to a politically ignorant electorate. This, more than Trotsky’s assertions, indicates the low level which rules among the so-called Communists in Russia. It is not, therefore, surprising to be told that the majority organise regular bands of “Communists” to break up opposition meetings by means of catcalls and whistling in chorus.

Trotsky’s programme

The reader will have noticed that the evils which afflict the Russian worker are very much the same as those which afflict us here or in any other country where the basis of the economic system is capitalism.