Book reviews – Pirani, Goodwin, Brown / ILP exhibition

Blast from the past

Blast from the past

Communist Dissidents in Early Soviet Russia. Five Documents translated and introduced by Simon Pirani. Matador, 2023.

When the state-capitalist one-party dictatorship in Russia finally collapsed in the early 1990s the state’s archives were opened to the public. Researchers have since dug out material from the period immediately after the end of the civil war in 1921 when working-class discontent was high and some freedom of discussion was still allowed inside the Communist Party,

None of the documents here have been translated into English before though one was published in Russian, outside Russia, in 1923. They reveal the personal and political disappointment of some Communists that the Russian revolution had not lived up to its claims and their expectations that it would bring about ‘the emancipation of the working class’ but had led, rather, to the emergence of a corrupt and self-serving ‘new bourgeoisie’ made up of full-time Communist Party officials.

The most interesting analysis here is that of the ‘Collectivists’, a group inspired by the ideas of the Old Bolshevik (and old opponent of Lenin) Alexander Bogdanov. Their basic position was that the working class had to have prepared itself ‘culturally’ to run a socialist society before it could be established. Starting from the position that the Russian revolution had been an attempted workers’ revolution they came to the conclusion that it could not have led to socialism since this condition for it was not present:

‘We accept that before the war the proletariat in its majority was not socialist, but began to change under the impact of the war. The socialist revolution began in the working class; the revolution arose in the formation of its consciousness of struggle; the proletariat found the will to overthrow the bourgeois order and to try to seize power. But that socialist revolution in the proletariat is far from complete. Not all of it has a consciousness of struggle. And the organisational consciousness of the whole proletariat has not been formed. New organisational methods, the entirety of which is a product of proletarian culture, still have to be worked out and integrated into working-class consciousness. Without this and before this, a socialist revolution in society is in our opinion impossible’.

Basically, no socialism without socialists. This was part of a wider argument that classical capitalism was collapsing and that the world was heading for a state capitalism ruled by a technical intelligentsia (what was later called ‘the managerial revolution’). This, they said, was what was happening in Russia under the Communist Party. Socialists there should personally take part in developing or implementing modern technology, another essential precondition for socialism.

The two other groups whose views are presented here — the Workers’ and Peasants’ Socialist Party and Workers’ Truth (Workers’ Pravda)— made the same analysis, though in a less worked-out form, that Russia was developing towards a state capitalism ruled by a new bourgeoisie.

The two personal views are only interesting as providing some context. It is striking how many of those mentioned in the book were, according to the footnotes, murdered by the Stalin government in the 1930s.

It’s a pity that such criticisms from inside Russia were not widely available during the time when ‘the nature of the USSR’ was a burning issue; they were way ahead of Trotskyism. Today they are only of historical interest. Pirani, in his introduction, hints at this when he writes that ‘social revolutions in this century may have as little in common with the Russian revolution as it had with the French Revolution of 1789.’

ALB

Vague and Vacuous

Vague and Vacuous

Values, Voice and Virtue: the New British Politics. By Matthew Goodwin. Penguin £10.99.

Goodwin was co-author of National Populism, reviewed in the March 2019 Socialist Standard, which was largely an unconvincing and unpleasant defence of a xenophobic form of nationalism. His latest book is no better.

The basic argument is that, since the 1970s, there has been a revolution or re-alignment in British society and politics. Thatcher supposedly emphasised family values and individual responsibility, but also ‘ushered in the new era of hyper-globalization’, as if this was government policy rather than part of the way that capitalism works; this involved, for instance, selling off ‘many of Britain’s assets’. The former ruling class of industrialists and landowners was replaced by ‘a new middle-class graduate elite’. The latter attended top universities, and were not just journalists, politicians and broadcasters, but also academics, doctors and architects. They have allegedly made it much harder for white boys from a manual working-class background to get into university. They control Britain’s main institutions, and a third of MPs have postgraduate degrees. Many of the elite are radical ‘woke’ progressives, a group that apparently constitutes about one in six of the population.

It is noted that Britain has become more unequal, and there are some passing references to very wealthy people, such as the ‘international jet-setting elites’ who have homes in London but also in New York and so on. Yet overall the author has not the slightest idea of how capitalism operates, of the division between a tiny minority who own and control the planet’s resources, and the rest, who have to work for them. The decline in manual jobs is noted, and much is made of the geographical divide between London and the rest of the country. But in London a quarter of the population live in poverty and one in fifty are homeless, though the reader would not gather this from Goodwin’s treatment.

It is correct to say that choice was reduced in politics as Tories and Labour grew closer together. However, the book’s focus is very much on England, with no discussion of parties such as Plaid Cymru or the SNP. The claimed counter-revolution against the new rulers involved three revolts: populism, Brexit and Boris Johnson. Brexit, we are told, was intended to reduce immigration and ‘restore Britain’s national sovereignty’ (whatever that is). Despite his privileged background, Johnson was ‘a renegade member of the elite’ and became leader of the non-graduate majority who supported the counter-revolution. But Partygate derailed this, and Truss’s ‘small-state, low-tax’ vision of Brexit failed as it had little popular support (nothing to do with market reactions, then).

The whole book is a fantasy, with no arguments to show how the supposed former ruling class have been replaced by the graduate elite, and no understanding of how politics under capitalism is driven by economic interests and the need for profit.

PB

Clubbable

Clubbable

Clubland: How the Working Men’s Club Shaped Britain. By Pete Brown. Harper North £10.99.

The author describes working men’s clubs as ‘the biggest ever working-class social movement’. He provides an entertaining description of their history, enlivened by accounts of visits to specific clubs. One of these is the Red Shed in Wakefield, where the Wakefield Socialist History Group has hosted talks by Socialist Party speakers.

Clubs originated under paternalistic attitudes of people who wanted to provide male workers (industrial workers, originally) with an alternative to the pub. The Club and Institute Union (CIU) was established in 1862, and had a number of rich and often aristocratic patrons. Gradually, though, clubs became more democratic, run by committees of their own members, and in many cases it was the members who maintained and refurbished the buildings, without being paid for this work.

Clubs benefited from the licensing laws that applied to pubs but not to private clubs. They were not just about serving beer, as they also provided facilities such as snooker tables, reading rooms, concerts and lectures by invited speakers. In 1887 William Morris spoke on ‘Monopoly’ at the Borough of Hackney Club, but was taken aback at all the coming and going in the audience, waiters serving food and so on. Brown describes the Bloody Sunday demonstration that year, which was attacked by the police, as being held by ‘the London radical clubs’ (though some accounts mention others that contributed to organising it). Political activity gradually shifted to other locations, however. Many well-known names began their careers performing in clubs, such as singer Tom Jones, racist ‘comedian’ Bernard Manning and snooker-player Steve Davis.

An obvious question is the status of and attitudes to women in these working men’s clubs. Women were originally not allowed to join, but gradually things began to change and by the 1950s most clubs had ‘lady members’. The clubs could hardly survive without the income from and practical contributions by women, but it was only in 2007 that women achieved equal rights in clubs, after various campaigns and shortly before the 2010 Equalities Act. Bingo made clubs even more appealing to women.

The clubs have of course had their ups and downs over the years. The breathalyser and the smoking ban hit attendance and bar takings. Musical styles such as glam rock and punk were hardly suitable for them. In 1922 there were 1,150,000 members in over two thousand clubs. Nowadays 1500 clubs are affiliated to the CIU, with around a million members, though there are also clubs which are unaffiliated. The north-east of England is ‘the undisputed heart of clubland’.

An informative account of an institution that figures little in most social histories.

PB

Exhibition review – ILP, old and new

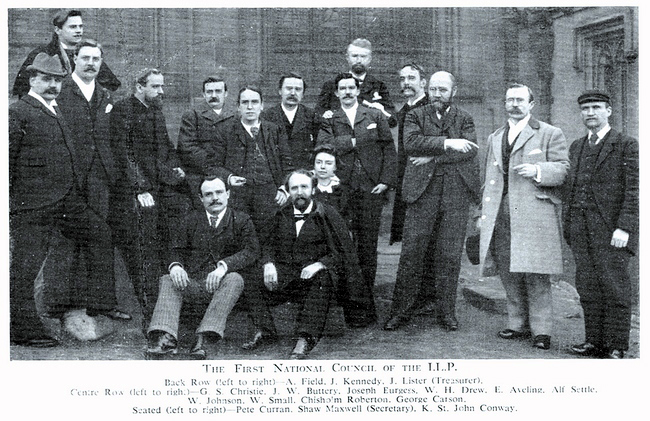

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was founded in 1893. To mark the 130th anniversary, the Working Class Movement Library (WCML) in Salford ran an exhibition ‘That Impudent Little Party’ in the final months of last year. It comprised original pamphlets, handbills and photos, supplemented by posters discussing the party’s ideas and history.

At its founding, Keir Hardie, who was one of the ILP’s leading lights, stated that it was an expression of a principle rather than an organisation, as it had ‘neither programme nor constitution’. In fact it did have an aim, ‘collective and communal ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange’, but this is contradictory, as ownership in common excludes exchange. In reality it stood for a series of reforms, such as abolishing the monarchy and the House of Lords, and doing away with indirect taxation.

The ILP was officially pacifist in the Boer War and the First World War, but many members did join the armed forces in the latter conflict. In the Spanish Civil War it was an ally of the Trotskyist POUM, which naturally brought it into conflict with the ‘Communist’ Party of Great Britain. The ILP was opposed to the CP, as it thought there was no need for a revolution, but there were informal links between the two parties, and some ILPers (members of the so-called Revolutionary Policy Committee) left to join the CP.

The ILP lost influence after the Labour Party adopted Clause 4 in 1918, which also inconsistently combined common ownership and exchange. In 1932 the ILP disaffiliated from the Labour Party and, in the words of a WCML poster, this left it ‘caught between’ the Labour government and the CP. Many people were now wondering what the ILP was for. In 1945 it decided not to rejoin Labour, and many members resigned. It struggled on to 1975, when it was eventually disbanded. Its successor is Independent Labour Publications (www.independentlabour.org.uk), which rejoined Labour that same year and campaigns pointlessly for a more left-wing Labour Party.

The ILP lost influence after the Labour Party adopted Clause 4 in 1918, which also inconsistently combined common ownership and exchange. In 1932 the ILP disaffiliated from the Labour Party and, in the words of a WCML poster, this left it ‘caught between’ the Labour government and the CP. Many people were now wondering what the ILP was for. In 1945 it decided not to rejoin Labour, and many members resigned. It struggled on to 1975, when it was eventually disbanded. Its successor is Independent Labour Publications (www.independentlabour.org.uk), which rejoined Labour that same year and campaigns pointlessly for a more left-wing Labour Party.

The first issue of the Socialist Standard argued that ‘the working class should have nothing to do’ with the ILP. Socialists continued to criticise it as a left-wing reformist organisation throughout its existence (see October 2009 Socialist Standard. Like other attempts to push or pull the Labour Party leftwards, it got precisely nowhere and eventually disappeared.

PB