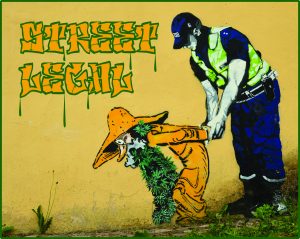

Street Legal

‘Marihuana is… a violent narcotic – an unspeakable scourge – The Real Public Enemy Number One! Its first effect is sudden, violent, uncontrollable laughter; then come dangerous hallucinations… fixed ideas come next, conjuring up monstrous extravagances – followed by emotional disturbances, the total inability to direct thoughts, the loss of all power to resist physical emotions… leading finally to acts of shocking violence… ending often in incurable insanity. Something must be done to wipe out this ghastly menace…’ (Opening foreword to the 1936 film Reefer Madness).

Now that the prohibition against cannabis has been officially overturned in Canada and Uruguay and the smart money predicts a domino-like cascade as other governments follow suit, hindsight will draw its own conclusions about this whole bizarre era. Historians may well look back at the epoch of cannabis prohibition and conclude that there really was a kind of reefer madness going on, only it wasn’t the pot smokers who were suffering from it.

Marxist theorists, unlike conspiracy theorists, do recognise that things happen by accident. Not everything has an intention and purpose, and while capitalism has its own internal logic, the human participants in it sometimes ignore that logic and instead follow the volatile whims of cultural prejudice and supposed moral imperative. When you take a walk past the history of drugs prohibition, you smell a powerful whiff of paternalism, racism and class condescension.

Cannabis through history

Cannabis was familiar to ancient societies from Scythia and Assyria to Greece and Rome, but almost forgotten in the West until reintroduced via the good offices of the Nineteenth Century East India Company, that paragon of capitalism whose enforced China opium trade on behalf of the British government is too well known to revisit here. Cannabis became popular among upper-class bohemian types on private incomes, but like cocaine and opium it was expensive and hard to get, and thus there was no move to ban it. Indeed the Victorians were avid fans of unregulated free markets, so that cocaine and opium were being enthusiastically shoved into everything from ladies’ tonics to baby teething ointments.

But it was another matter when the workers started getting hold of cannabis. Then it was a case of moral panic. For, as everyone knew, the ‘worker’ was little better than a beast and everything must be done to avoid arousing their basest urges, lest they fall into unchristian vileness (e.g. murder each other or, more to the point, fail to turn up for work).

There is a long history of attempts to prohibit everything poor people might enjoy. Easily persuaded of their own moral, cultural and genetic superiority, the European ruling classes for centuries have had a condescending and paternalistic attitude to the labouring classes. For some reason that was obvious to them but never explained to anyone else, the same self-indulgence which made them the cultured and refined jewels of polite society would turn workers into stampeding swine if they ever got their hands on it.

Thus the anti-gin campaigns against ‘Mother’s Ruin’ in the Eighteenth Century. Music and dancing had earlier been banned by the Puritans. And it wasn’t just drugs and rock ‘n’ roll. Sex too (known as ‘lewdness’) was considered a corrupting influence, so that the erotic artwork excavated from Pompeii was kept in a ‘secret museum’ in Naples to which only ‘gentlemen’ had access (this exhibition only became permanently open to the public in 2000, albeit still age-restricted).

What made cannabis even worse was that it was seen as a ‘black’ drug. Coming from the colonies, it became associated in Britain with Asian sailors and black denizens of the demi-monde including actors and prostitutes, and later in the USA with Mexicans who started bringing it across the border. The mix of class condescension and white racism made for a poisonous cocktail.

So it was that Britain started banning cannabis in its colonies from the 1840s onwards, and the process of creeping prohibition spread. It was one thing to sponsor an opium trade in China, after all, but quite another to have stoned workers in one’s own factories.

The First World War saw a further moral panic (largely imagined) about drugs in the trenches. This led to a British ban on opium, cocaine and cannabis in 1916, and propaganda-fuelled legislation followed in the 1920s. The post-war mood became more hard-line. Temperance had long been in the air, and wartime propaganda had portrayed the Germans as boozy-beer-barrels-on-legs. Now the opprobrium extended to other drugs. The Versailles treaty stipulated, among other things, a considerable reduction in Britain’s continued involvement in the international opium trade.

The rest was laziness. It was easier to blame drugs for social ills rather than look at the social ills themselves. Thus drugs came to be seen as everything that was wrong with society and especially with its disaffected youth. The transcendental evil of illegal narcotics was dinned into the public consciousness by increasingly hysterical propaganda, including the preposterous (and later cult) cinema classics Reefer Madness (1936) and Assassin of Youth (1937).

The absurdity was that, at that time, hardly anyone could get hold of these drugs anyway. But globalisation changed all that with a tidal wave of cheap product which provided a get-rich-quick scheme for the enterprising poor as well as fuelling an unprecedented addiction epidemic. Governments were slow to realise the extent of the underground drugs trade, and when they did they simply followed established procedure and enacted ever-more draconian criminal legislation. Arrests and prison sentences rocketed by orders of magnitude, but this only served to push up prices and make the mafia syndicates and cartels ever more powerful. The world sleepwalked into drug prohibition, and woke up to an organised crime economy that today is bigger than Google or Microsoft.

A revolutionary socialist who wants to overthrow capitalism is not interested in advocating reforms within capitalism, or even expressing preferences about how capitalism ‘ought’ to be run. But it is merely stating the obvious to say that banning drugs, particularly popular ones like cannabis, has been a huge mistake. And it’s a mistake that’s cost the lives of countless thousands. The average life expectancy in Mexico has actually lowered due to the sheer number of drug-related murders (New Scientist, 9 April 2016).

A slice of the pie

If the end is really in sight, there’s no great mystery why. What capitalist investor doesn’t want to get a piece of a half-trillion dollar pie? When money talks, lawyers listen. For governments too the logic is irresistible. In the UK alone the potential tax revenue is estimated at £1bn a year. And there are savings too. It costs around £50,000 a week to incarcerate a prisoner in the UK, and prisons are overcrowded. Locking up people for smoking weed – a victimless crime, after all – is simply throwing money away. That’s why around 50 percent of UK police authorities have given up prosecuting anyone for possession, and Durham Constabulary has taken the adventurous step of permitting ‘official’ local home-grower clubs, provided the weed is for personal use only (BBC documentary ‘Is it time to legalise weed?’, July 2017).

Though now past its use-by date, the UK anti-weed propaganda machine grinds on (‘Father tries to murder baby son, judge blames cannabis’, BBC News, 8 November). UK politicians continue to fear the legalisation argument is a vote-loser. After a century of brainwashing against lifestyle drugs, the volte-face is still considered too hard a sell. And there are other problems. There’s no logic for legalising cannabis that doesn’t also apply to every other illegal drug. Most of them are cheap to make, and none of them are as dangerous as alcohol or tobacco. Furthermore, legalising weed alone may turn out to be a disastrous half-measure, like a farmer destroying one crop pest only to make room for another. If the bottom drops out of the weed market, UK growers on £7k a month won’t be resorting to welfare cheques. Instead they’ll be looking to start shifting other drugs in bulk.

From a socialist point of view, capitalism is a social system owned and ruled by the wealthy through their various puppet governments, with precious little real democracy and even less informed debate. Sure it’s unfair, but it’s also inefficient, incompetent and unresponsive. It’s as if the social train is empty because everybody apart from the guy in First Class has been made to get out in the snow and push. It’s not hard to see how mistakes are made, or why they take so long to correct, when only the prejudices of the rich elite are taken into account. If and when cannabis is legalised, it’s the corporations and investors who will be partying. Your daily life as an exploited worker is not going to change a whole heap just because you can walk down the street smoking a legal spliff.

But there is a question for socialists, nonetheless. To be clear, socialism is a global system of democratic participation, common ownership and production for use, where property exchange and money will not exist. Think of it as a global volunteer collective. Whatever is done, is done free, and whatever is available, is freely available. Some people imagine this means having no restrictions of any kind. But you can easily see why this is wrong. People in socialism are not going to want stoned airline pilots or eye surgeons, or young children feasting on cocaine or heroin either. In practice some forms of restriction must surely be put in place, even in a society with more freedom than any in history. What these are and how they are implemented is a matter for discussion in socialism. It’s possible that, like that other opium of the people, religion, there may be a declining interest in psychoactive drugs when daily reality is no longer the heavy oppressive experience that capitalism offers. It may be that nobody will choose to spend their time making these drugs, given that there will be no ‘market’ for them anyway. But it seems unlikely that drugs will go out of style, given that they have been around since humans first learned how to knock two flints together. There’s no denying it, drugs can be fun, and that will be true in socialism too. This is just one of the issues a democratic society will have to deal with. But what it won’t do, and can’t do because nobody will have the right or the authority to do it, is ban them from the face of the Earth.

PADDY SHANNON

(This article first appeared in Poliquads Magazine: https://www.poliquads.com)