The world steel crisis

The Labour government, as its White Paper published at the end of March on the British Steel Corporation shows, has once again been forced to face up to the realities of capitalism. Its policy of pumping money into a bankrupt industry in order to try to preserve jobs is to be abandoned.

Anyone with the slightest knowledge of how capitalism works could have predicted that such a policy could only be temporary since it goes against the whole logic of capitalism, which is to produce wealth to be sold at a profit not so as to provide jobs for workers. In effect it poured money raised by taxes on other sections of capitalist industry down the drain; something which no government can do indefinitely. The House of Commons Select Committee on Nationalised Industries which, under a Labour chairman, is the watchdog for the capitalist class on such matters had already said “enough, no more”. The Labour Government has now bowed to the inevitable and fallen into line with the logic of capitalism.

It is an interesting story which illustrates the futility of the reformist policy of trying to make capitalism work other than as an unplannable profit-making system. In February 1973 the then Conservative Government proposed closing a number of steel works. The Labour Government, elected in 1974, reversed this decision and told the BSC to keep them open for a longer period. Now only three years later the Labour Government itself proposes “early closure dates” for these same plants on the grounds that they are a burden to the BSC’s finances and productivity. The White Paper openly recognises this as a breach of previous promises:

It must be recognized that the proposed advancement of these closure dates involves serious departures from previous understandings and commitments made by the British Steel Corporation (British Steel Corporation: the Road to Viability, Comnd 7149).

It does not say, however, that the BSC made these commitments under instruction from the Labour Government. We recognise the problems of the steelworkers who will be losing their jobs in a time of high unemployment. They are victims of the operation of capitalism whose inexorable law of “no profit, no production, no employment” cannot be overcome by the action of any government nor, we might add, by the most militant trade union action. Many of the workers involved seem to realise this and have switched their demands from trying to keep the plants open to trying to get as big a redundancy payment as possible.

The crisis in the steel industry, which is worldwide and not just confined to Britain, illustrates very neatly the anarchy of capitalism and how it leads to periodic crises in particular industries.

There are three main steel producing and trading groups in the world. The United States, Japan and the Common Market. The Common Market can legitimately be treated as a single unit since, under the 1952 Treaty of Paris which set up the European Coal and Steel Community, the Commission in Brussels has considerable powers in this field and is charged with managing the common affairs of the steel industries in the nine member States, essentially those of Germany, Britain, France and Italy.

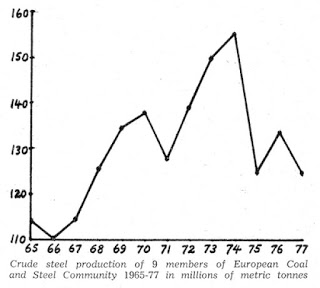

In the years 1973 and 1974 the steel industry was booming, as our graph of ECSC production of crude steel over the last twelve years shows. In these conditions the various capitalist and state capitalist enterprises involved, in Japan and America as well as in Europe, planned massive expansions of their productive capacity, not to mention the plans for new steel works in the so-called Third World. In 1973 the BSC, for instance, adopted a development “plan” which involved increasing its crude steel productive capacity from the 29 million tonnes it was that year to 43 million tonnes in the 1980s.

In the years 1973 and 1974 the steel industry was booming, as our graph of ECSC production of crude steel over the last twelve years shows. In these conditions the various capitalist and state capitalist enterprises involved, in Japan and America as well as in Europe, planned massive expansions of their productive capacity, not to mention the plans for new steel works in the so-called Third World. In 1973 the BSC, for instance, adopted a development “plan” which involved increasing its crude steel productive capacity from the 29 million tonnes it was that year to 43 million tonnes in the 1980s.

Under the pressure of competition each enterprise and each country expanded its productive capacity to meet the booming market demand which each assumed would continue. The result was that their total productive capacity came to exceed by far the market demand. A crisis of “overproduction” broke out in 1975 and production fell drastically.

The White Paper describes the situation, frankly bringing out the perils of “planning” under capitalism.

There are two main reasons for the serious problem of world over capacity for steel-making. First, a huge amount of modern, highly productive new capacity was either completed or under way in Europe, Japan and the developing world before the Middle East war in October, 1973, and the steep rise in energy prices that followed it.

When this new capacity was built or planned, continued expansion in world industrial activity was widely expected with a sustained growth in the demand for steel.

Instead—and this is the second factor—the growth of world industry has, in recent years, fallen well below the rates predicted before 1974.

All such forecasting is subject to a wide margin of error as subsequent events have shown. Demand for steel has tended to decline—at the very time when much of the new capacity was only just coming on stream.

This is a classic case of “overproduction” caused by the anarchy of capitalism. The steel industry has had such crises every four or five years: 1961, 1966 and 1971 were, like 1975, years in which production fell compared with the previous year. But on all these occasions production resumed its upward trend the following year. It was expected that the same pattern would be followed in 1976. “The recovery may not be uniform but on the whole it is encouraging”, wrote a German journalist that year in an article featured in four leading European newspapers. “After the worst recession for decades, affecting most of the world’s steel industry in 1975, the leading figures in the industry face the future with unwearied optimism” (The Times, 26 October

1976). So, optimistically, the steel enterprises planned to expand production again. Let the White Paper continue the story, again illustrating the unplannable nature of capitalism :

By late 1976, with some new capacity coming on stream and with improved performance at other plants, BSC was well placed to supply demand at a time when it was generally expected that there would be an upturn in Britain and in the world as a whole.

Instead, there was a further downturn in demand at home and overseas. United Kingdom demand for steel has fallen by 23 per cent since the 1973 peak instead of the continued growth then expected. The industry is currently operating at about two-thirds capacity, the same as Japan. Other EEC countries are operating at about 60 per cent of capacity and the United States at about 75 per cent.

Slowly, as 1976 did not show the expected recovery and 1977 proved to be as bad as 1975, the steel enterprises began to realise that they were faced with something more than the usual temporary “overproduction” of previous recession years. They began to talk of a more basic, “structural”, problem of “overcapacity” for which there was only one solution: mass sackings and closure of plants. In other words, the destruction of the “excess” productive capacity.

The Labour Government’s White Paper is in line with this solution which is quite rational by the logic of capitalism, but irrational and even criminal from the point of view of human needs and interests. For there is no real “world over-capacity for steel-making” as the White Paper claims; there is only excess capacity in relation to profitable market demand. From the human point of view, not enough steel is being produced; there is a real human need for more steel and steel products to construct, for instance, houses, hospitals, power stations, bridges, railways, etc. But this does not interest capitalism, so world steel-making capacity is to be cut back until it is in line with what does count, profitable market demand.

The steel industry, in Britain and elsewhere, will eventually recover from this crisis—even if this involves destroying part of its existing productive capacity. But there is no telling how long this will take. One German steel baron, Hans Birnbaum, chairman of Salzgitter (whose losses in 1976 amounted to £25 million) has been reported as stating that

competition on the world steel market was now so strong that there would be no quick reduction in the overcapacity situation—at least while demand for steel grew only slowly. Annual world steel production was about 700 million tonnes against a capacity of 900 million tonnes, and there had been considerable expansion of capacity in Japan in the past few years. The Japanese exports to the EEC, he said, were only relatively small in terms of the size of the total market, but their exports to third world markets were ruining EEC steel sales in those countries (The Times, 19 April 1977).

One thing is clear, however, the adjustment of productive capacity to market demand will be as chaotic and anarchic as was the expansion of productive capacity which led to the 1975 crisis. We can expect to see a three-sided trade war between Japan, Europe and America, with America trying to keep Japanese and European steel out of its home market and Japan and Europe competing fiercely for external markets as indicated by Birnbaum. The Common Market too will be under strain as Britain. Germany, France and Italy struggle to shift the burden of production cuts on to each other. This chaos is just capitalism working in a normal way.

Adam Buick