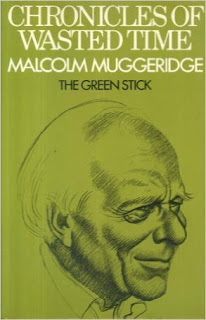

Chronicles of Wasted Time, Part I, by Malcolm Muggeridge, Collins, £3.00.

Chronicles of Wasted Time, Part I, by Malcolm Muggeridge, Collins, £3.00.Fourteen years ago Walter Allen’s novel All in a Lifetime created a stir by depicting the formative years and ripeness of the Labour Party, and then conveying that a misjudgment of society had been made and it had turned out irrelevant. This first volume of Muggeridge’s autobiography covers the same ground, but is different in that the recollections are real not fictional and the result is not perplexity but animated sourness.

Muggeridge’s father was a Fabian who became an early Labour Councillor and, eventually, an MP, and the book gives an account of home life in that atmosphere—parlour discussions, meetings with MacDonald, Dalton, etc., and a Tolstoyan “colony” at Stroud. Muggeridge recalls it all subjectively and, to a large extent, derisively. “It was a kind of revivalism without tears; sinful men were to be washed, but not in the blood of the Lamb; in, as it were, municipal water, with carbolic soap purveyed by the co-op.” Later, visits to Five-Year-Plan Russia are described as if it were a crude but fortunately transparent attempt at personal fraud on the writer.

These reactions are common. One can meet anywhere men of Muggeridge’s generation who shared the faith that beneficent reform would conquer all society’s ills. The hopes of an “intellectual, moral and aesthetic transformation” through universal State education, and slums “transformed into garden cities” by Planning Acts; what has been produced is not so much disappointment as a sense of having been swindled. Recalling pacifist talk in his youth, Muggeridge writes of their conviction that the arms manufacturers were the cause of all the trouble: “how surprised we should have been,” he says, to know that trading in arms by Labour governments would far exceed the evils of private enterprise.

Yet the illusions were self-created by those who believed all this. The choice between reform and revolution was put before the social-democrats at the beginning of this century, and the majority elected for reform. No notice was taken of Socialists pointing out the all-too-obvious fallacy of—to use one of Muggeridge’s own metaphors—”building a housing estate on the slopes of Etna”. Despite everything a century’s experience should teach, reformists go on being hopeful like bingo-players that the next try will be lucky, afterwards to sit chewing peevishly on “a civilisation dropping to pieces” and “credulous armies of the just”.

What is notable also is Muggeridge’s lack of contact with workaday life and people. He acknowledges this in speaking of some earthy-proletarian relatives in the North, tries to dismiss it by calling the working class a fantasy invented by Marx, Engels, Morris and D. H. Lawrence, but without showing comprehension of what it really means. Thus, he writes of the start of married life: “We had very little money . . . certainly not more than £100” . . . in the early ‘twenties when £100 was a year’s pay to many working men! The remark echoes one made in a TV programme a year or so ago when, denouncing birth control and answering a woman who supposed he had always been comfortably-off, Muggeridge said indignantly: “It’s quite untrue. It was 1939 before I earned even £1,000 a year”—and appeared oblivious to the thrill of half-amused astonishment in the audience.

And one other curiousity, considering Muggeridge’s prominence in crusades against what they call the permissive society. He relates weightily the sexual preoccupation of his marriage in its early days: “Rolling about, now one on top, now another; grunting, coaxing, sweating, murmuring, yelling . . . We looked to our bodies for gratification, which we felt they owed us.” But that was fifty years ago, before pornography and the pill and Oh, Calcutta! had come to make satyrs of us all. Doesn’t that give away the whole present case for Muggeridge!

Robert Barltrop