A number of novelists, from time to time, have written books that revolve around some particular industry. The stories, if they are the product of a knowledge of the industry plus good writing, can be both informative and entertaining.

A really first-class book of this kind is “

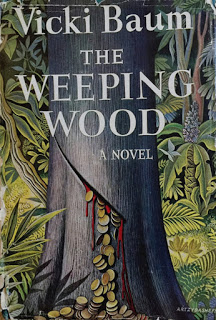

The Weeping Wood,” by

Vicki Baum, published in cheap edition by Michael Joseph for 6s. Here is the story of rubber from the days before the discovery of America, when the Amazon Indians found the tree which they called Cahuchu, meaning weeping wood, up to recent times, when the German I.G. Company and the American Standard Oil Company competed and cooperated to produce a synthetic rubber.

Each chapter of this story is a separate episode in the history of rubber; each chapter is a separate story linked by this main historical theme. Only in a few instances do the same characters appear in the different chapters. In the introduction the author tells us that the story,

“. . . contains as much fact as if contains play and make-believe; . . . All the facts and figures, the details of history and background, all notations pertaining to rubber are authentic, as are, evidently, the documentary fragments scattered about. On the other hand, all the characters are inventions, bubbles of fantasy; all save the few historical ones which appear briefly in the course of these tales, but are also presented in more or less fictitious situations.”

The story portrays for us how the Amazon Indians used Cahuchu gum to make toys for their children and how a Jesuit missionary brought a pair of sticky, smelly, moulded shoes to a high priest of his order, only to be outwitted and robbed of his discovery by an unscrupulous church financier and a native boy.

It then swings to the middle of the 19th century to tell of the struggles of Charles Goodyear to raise enough money to carry on his experiments to improve rubber fabrics, to make them impervious to heat and cold and to remove their evil smell whilst still retaining their elasticity.

We learn of the intense exploitation of men and women who lived tough and lonely lives in the Brazilian jungles gathering the gum; how seeds of the rubber tree were illegally exported from Brazil and sent to Kew, where seedlings were raised and shipped to Ceylon to start rubber plantations. The story then transports us to the rubber plantations of Sumatra to tell of planters and native workers; back again to America to show the methods used to intensify the labours of the workers in the rubber tyre factories at Akron and of the workers’ struggles to organise in unions to resist their employers; return to Brazil after the crude rubber monopoly was lost to that country to see the effect of the one crop system on the native population; then to Germany during the last world war to tell of the frantic efforts to discover a synthetic substitute. The story ends in Washington, where efforts are still being made to find the perfect synthetic substitute, and where there is political manoeuvring to make America independent of world supplies of crude rubber.

Here is a story that reveals every unscrupulous trick and dirty device that has been conjured from the mind of man to wring profit from the exploited rubber workers, whether in the jungle, on the plantation, in the factory, or in the laboratory; it reveals the total indifference to human suffering in the scramble for profit from rubber; it shows how the booms and the slumps of capitalist trade, as well as its wars, have affected the rubber industry and the lives of the workers employed in it

This is a good six shillings’ worth. It is the only book of its kind that Vicki Baum has written. Her other novels may be good, but they have not the same social significance as “The Weeping Wood,” they are as different from it as chalk is from cheese.

One of the foremost writers of this type of novel, perhaps THE foremost, was

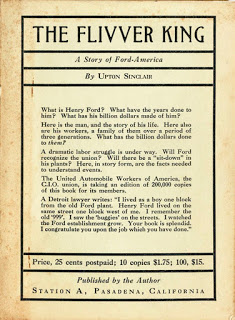

Upton Sinclair. In his early days he wrote magnificent stories round a number of different American industries. Some of them have recently been republished by Werner Laurie.

“The Jungle” (10s. 6d.), originally published in 1906, was the first of these books and the one that made Upton Sinclair famous. It caused an international sensation by revealing the horrible conditions that prevailed in the American meat canning industry. It caused an investigation to be made, followed by a revision of the Federal meat inspection laws by the U.S.A. Congress. It is a gruesome page in working-class industry and, despite its date, is still worth reading.

“Oil” (10s. 6d.) was first published in 1927 and, as the title implies, it deals with the oil industry.

“Little Steel” (8s. 6d.) has as its theme the struggle between workers’ and employers in the iron industry. First published in 1938.

“The Flivver King” (7s. 6d.) tells the story of Henry Ford and the workers in the American automobile industry. This is a particularly good story. First published in 1938.

These books by Upton Sinclair should not be confused with his “World’s End Stories,” which he has written in recent years. In our opinion the books in this series do not compare with his earlier work. There are many other books that Sinclair has written which have not been republished in late years, but which may sometimes be found on secondhand bookstalls. “Boston” is one. It narrates the story of Nicola Sacco and Bartelomeo Vanzetti, who were condemned to the electric chair in 1927. The “Socialist Standard” for September, 1927, had this to say of the Sacco and Vanzetti case

“The workers, generally speaking, have assumed their innocence, and have seen in the case the vindictiveness of a ruling class which manipulates the machinery of the law against property-less wage-earners.”

“Mountain City” deals with the coal industry; “The Wet Parade” deals with prohibition in America, and “Sylvia’s Marriage” deals with venereal disease. There are many more of Sinclair’s books that we have never read and some that we have read but cannot recommend.

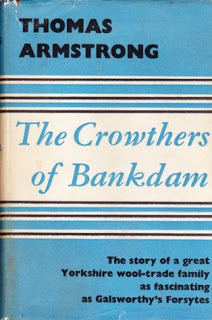

A more recent author who takes an industry for the theme of a novel is

Thomas Armstrong. His first book, “

The Crowthers of Bankdam,” published by Collins for 10s. 6d., is outstandingly his best. He gives us the history of the English woollen industry during the past hundred years. The story opens at the time of the Crimean War, when hand looms were almost extinct, having been ousted by power-operated ones. Prior to that time many Yorkshire Cottages had boasted a hand loom, but with the application of steam power, those who could muster a little capital brought small numbers of workers under a common roof to produce woollen cloth with the new power looms. Soon the hand looms were discarded and left cluttering up back gardens and waste plots of land where they were thrown, not worth their weight as junk.

This was the period in the woollen industry when small capitalists were laying the foundations of the vast fortunes that were later required to expand their mills and their trade and enable their descendants of today to survive in a world where gigantic amounts of capital are required to launch and maintain an industry.

Simeon Crowther was one of those early capitalists, a hardworking, frugal-living, astute business man who, with his wife and family, worked in his mill beside his employees, building for the future the firm of Crowther and Sons, of Bankdam Mills.

Ben Pickersgill was a weaver, the father of a dozen children. As a sickly creature of four years of age he had been brought to Yorkshire amongst hundreds of other pauper babies.

“In the mill, he with rows of other wizened tots, had slept miserably under coarse brown blankets and horse covers until before the dawn during the greater part of the year, the brats’ overseer had clattered down the long, chill room, to rouse again to toil overstrained little bodies which often, so mercilessly driven, wilted and died . before there had been an adequate return on the capital outlay.” (page-48) .

But Ben survived and we find him in his kitchen, where,

“Abysmal poverty cried aloud from everything in it, from cracked pottery to makeshifts of all kinds. Poor tattered rags of underwear hung from a line over the fireplace. A torn strip of rug, a pitiable ameliorative striving to give some warmth to the damp stone floor, served but as a danger to the unwary walker.”

Out of child labour and the long hours of toil of the poverty stricken workers, the early capitalists were enabled to amass wealth and accumulate. That is where the story of the Crowthers starts and it proceeds down the years from generation to generation. Trade slumps and booms, wars, tariffs, bankruptcies—all play their part in determining the vicissitudes of the Crowther family fortunes. By the end of the story the firm owns a number of huge woollen mills, various subsidiary works and factories and has offices and representatives in many parts of the world.

The story, in the main, centres on the capitalist family, not on the workers. It shows the sharp practice, the double-dealing and the downright fraud that capitalists use to exterminate one another, even friends and relatives, in the cut-throat competition born of capitalism.

Mr. Armstrong has also written a lengthy novel on the cotton industry called “King Cotton.” We must confess, having had two bites at this book, we have given it up as indigestible. It fails to hold our interest, despite the loud acclaim of the critics when it was first published.

No matter what any of these authors claim for themselves, they are not Socialists. It has not been their task to find remedies for the evils that they have depicted or solutions for the problems that they have revealed. But in very entertaining form they have shown us the evils and brought us face to face with the problems! They have something to teach, we have much to learn.

W. Waters.

A number of novelists, from time to time, have written books that revolve around some particular industry. The stories, if they are the product of a knowledge of the industry plus good writing, can be both informative and entertaining.

A number of novelists, from time to time, have written books that revolve around some particular industry. The stories, if they are the product of a knowledge of the industry plus good writing, can be both informative and entertaining.