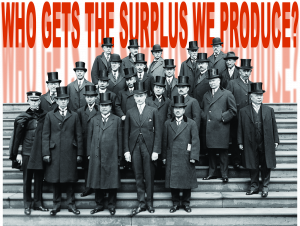

Who gets the surplus we produce?

The coronavirus crisis has demonstrated, as if it needed demonstrating, that it is the working class who keep our society running and create the value in our society, not executives or financiers. We cannot repeat often enough: the source of profits for capitalists comes from the difference between the cost of paying for our ability to work, and the value of the goods we produce in the working time that we sell to them. Money cannot be turned into a greater money without the intervention of human labour somewhere in the story.

This simple relationship, between buyers and sellers of the ability to work, is the essence of capitalism. What complicates this relationship is what happens to the profits derived from this exploitation of human time. This surplus value, as Marx termed it, needs to be realised as money, through the final sale of the goods and services produced by the workers. There is no natural or essential way of dividing this surplus value: the various common divisions – rent, interest, commercial profit – are all just negotiated between the various types of capitalists who stand behind the buying of labour power.

To try and protect their investments, and to try and win over the greatest share of the surplus value they can get, the owners make agreements between each other, and they turn to the state to regulate and enforce those agreements. The owner of land sets conditions on its use, and expects to get a share based on the productive advantage their land provides relative to other plots. The lenders of money extract interest based on their perception of risk, the general profitability of the economy and how much money is available to lend generally. Chief executives get inflated salaries and bonuses. Shareholders get dividends.

Sharing the loot

These divisions, and the mechanism by which they can be allocated and enforced, are only limited by human imagination and ingenuity. In his book Moneyland Oliver Bullough describes how a group of London bankers tried to circumvent the post Second World War system of capital controls and currency stabilisation controls in the Bretton Woods Agreement. A banker called Ian Fraser was tasked with coming up with arrangements to create what later became called Eurobonds.

If the bonds had been issued in Britain, there would have been a 4 percent tax on them, so Fraser formally issued them at Schipol airport in the Netherlands. If the interest had been paid in Britain, it would have attracted another tax, so Fraser arranged for it to be paid in Luxembourg. He managed to persuade the London Stock Exchange to list the bonds, despite their not being issued or redeemed in Britain.

By this simple agreement to meet the requirements of regulators, Fraser et al were able to start moving around dollars stuck in Swiss bank accounts anonymously and tax free. This is a part of what Bullough terms ‘Moneyland’, a virtual no-place where money and other assets can disappear to reappear on the other side of the globe.

Such arrangements enabled the architects of such transactions to burst asunder the restrictions being placed on financial transfers, and make the financial market a global institution. Of course, as Bullough notes, the previous rule-based system was not neutral; the United States was keen to use its muscle as the world reserve currency to impose its will on other states. Just as the negotiations between the various strands of capitalists are contingent upon their power and ability to write the rules to their own advantage. There has never been a pure market, but always one in which actors can try to limit competition through changing the rules of the game.

This does cut both ways, as Grace Blakely in her book Stolen: How to Save the World From Financialisation, freeing international markets for money and finance means that ‘bond vigilantes’ can start to impose pressure on state policies through the threat of moving their capital or selling their currency. They watch the behaviours of governments and judge how conducive they are to profit making for investors. There is no conspiracy here, simply the operations of raw market power.

Thieves fall out

She joins many on the Left who see financialisation as a distinct trend of contemporary capitalism. Many on the left have effectively taken the side of industrial capitalists (‘who actually make things’) against the financiers, who are seen as parasitical. Of course, the reality is that both types of capitalist are exploiting workers, they just disagree over who gets what share.

According to Blakely:

‘Businesses once focused primarily on producing goods and services for which they had a competitive advantage, but today they are likely to place as much if not more focus on their share price, their dividend regime, their borrowing and the bets they’ve made on exchange rates and interest rates’ (p.13).

Such focus is rational because director’s bonuses depend on those factors. Also, dealing in abstract money as money has a safety factor compared to actually buying specific stocks of machinery and components which can be rendered obsolete by technological change. The competition between capitalists means trying to push as much risk onto others while maximising their reward.

In this journal we’ve previously reviewed Mariana Mazzucato’s The Value of Everything (July, 2018). In that book she observes of the financialisation thesis: ‘In the 2000s, for example, the US arm of Ford made more money by selling loans for cars than by selling the cars themselves’. Of course, there are more advantages to a firm doing this, debts can be packaged up and sold off, as in the infamous credit default swaps that featured so heavily in the 2008 financial crisis. Indeed, every transaction can be made subject to derivative transactions, they can be insured, hedged for and against, sold on futures markets and generally speculated upon.

As with the Ford example above, this can mean adding notional growth and assets to a company based on the income the company can expect and how it aligns with accounting rules. A vast machinery of human minds abstracts from the income derived from the work we do to create a notional second nature. This is Blakely’s finance led growth that she observes. It also inflates the notional value of company and national accounts.

The state steps (back) in

Coronavirus has disrupted this financial machine. As now arch-Starmerite writer Paul Mason noted in the New Statesman (18 March):

‘Every aspect of human life, in a developed society like our, is “securitised”. That is: my gym membership fees, the takings at my local pub, the profits of Starbucks, the bus and tube fares I pay – all are wrapped up into financial instruments into which a complex network of banks, hedge funds, insurance firms and pension funds invest in order to generate profits’ (https://tinyurl.com/rebmxaa).

He argues, correctly, that this financial architecture is not just superficial but integral to the whole economy, and the strains put on it by the lockdown are enormous. Its notional character is misleading, that financial architecture is real, and the product of human beings coming together and making complex arrangements, even if it seems irreducibly complex from the outside. It polices and disciplines states and corporations alike, on behalf of the owners of wealth. The $52 trillion in assets in the shadow banking sector he identifies as at risk are the profits extracted from our labour.

His suggestion, that the state will have to step in, is also correct, since there is no market mechanism to ensure the continuation of society, in the short term. This does not mean, as he suggests, that that will be a new economic system. The post-Second World War Labour government stepped in, and through nationalisation stabilised the economy and saved ruined industries (indeed, then as now, the crisis may well destroy the value of enough capital for those lucky enough to have wealth to invest to make a killing at the fire-sales of the bankrupts and for growth to resume on a rapid scale).

Capital controls, which he advocates returning to, would be jail-broken again as soon as the profitability was there. Dismantling financialisation will not improve the lot of the working class. Nationalising the banks just means nationalising commodity fetishism. We cannot repeat too often: exploitation happens because we sell our ability to work and capitalists use that ability to make a greater value of wealth. With respect to Spike Milligan, fear of the coronavirus should be transformed into the fear of wages.

PIK SMEET