Mixed Media: ‘LS Lowry’, & ‘Hedda Gabler’

LS Lowry

The Lowry exhibition currently at Tate Britain in London includes all the popular ‘matchstalk men and matchstalk cats and dogs’ paintings paid tribute to in the 1978 song by Brian and Michael. Lowry portrayed working class life in Pendlebury, Salford and Manchester from the economic depression of the 1930s to welfare state Britain of the 1950s or as John Berger wrote in New Society in 1966: ‘this is what has happened to the ‘workshop of the world’, the production crisis, the obsolete industrial plants’.

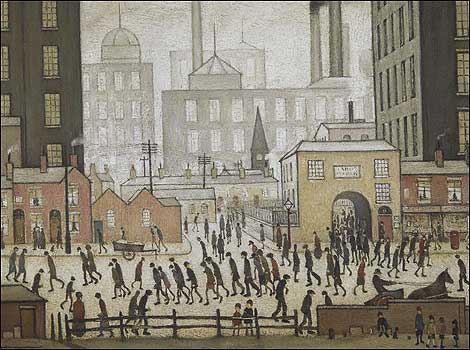

The ‘matchstalk’ paintings such as Coming Home from the Mill, People Going to Work, Returning from Work, Coming from the Mill and Outside the Mill are repetitive and convey the world of factory whistles, wage slavery and payday for the Manchester working class only a few generations after Engels wrote his investigative book.

Lowry’s more interesting work includes the 1926 A Northern Hospital which is fundamentally a workhouse (‘a Bastille of the proletariat’) which contrasts with the NHS in Ancoats Hospital Outpatients Hall from 1952. For all his ‘solid Lancashire conservatism’ Lowry quietly welcomed the post-1945 new world of the NHS and welfare state.

Lowry’s industrial landscapes and The Pond commissioned for the 1951 Festival of Britain are impressive panoramic views of industrial Manchester. The Pond with its smoking chimneys, terraced houses and the Stockport Viaduct was used as a Christmas card by prime minister Harold Wilson in 1964.

Lowry’s 1937 The Lake is all fetid spillage in an industrial scene and demonstrates clearly his opposition to sentiment in art and his statement that he ‘was affected and inspired by the beauty of the industrial scene’.

Going to the Match from 1953, one of his football paintings which the Professional Footballers Association bought for £1.9 million in 1999 depicts Burnden Park, home of Bolton Wanderers Football Club, which was the scene of a disaster in 1946 when 33 football fans were crushed to death. Football was central to masculine working class culture at this time and Burnden Park was later used prominently in the 1955 Arthur Askey film The Love Match.

The Funeral from 1928 and the cemetery in Necropolis of 1947 are a reminder of the centrality of death in life but also the financial cost. Today there is a rise in ‘public health funerals’ which is another name for ‘paupers funerals’ and the working class have to resort to pay-day lenders and credit cards to pay for funerals.

Although conservative in many respects, Lowry was an enemy of privilege and turned down all ‘gongs’ and a knighthood.

************************************************************

Hedda Gabler by Henrik Ibsen

Ibsen’s 1890 drama Hedda Gabler was recently staged at the Old Vic theatre in London starring Sheridan Smith as Hedda and Darrell D’Silva as Brack. The play is a plea for bourgeois liberal feminism but also a portrayal of a Nietzschean existential heroine. Hedda is in a lineage of strong women constrained by patriarchal society from Clytemnestra in Aeschylus to Medea by Euripides.

Ibsen’s 1890 drama Hedda Gabler was recently staged at the Old Vic theatre in London starring Sheridan Smith as Hedda and Darrell D’Silva as Brack. The play is a plea for bourgeois liberal feminism but also a portrayal of a Nietzschean existential heroine. Hedda is in a lineage of strong women constrained by patriarchal society from Clytemnestra in Aeschylus to Medea by Euripides.

Ibsen dissects middle bourgeois family life, its morality, niceties, home, hearth and happiness which Nietzsche castigated as ‘it is not your sin but your moderation that cries to heaven’. It is a place where women have a subordinate role to men and the expectation that Hedda become pregnant. In his preliminary notes Ibsen wrote ‘women aren’t all created to be mothers’ but Marx saw that ‘the bourgeois sees his wife as a mere instrument of production’. Hedda refers to ‘love’ as ‘that glutinous word’. Alexandra Kollontai saw that ‘the outward observance of decorum and the actual practice of depravity, and the double code, one code of behaviour for the man and another for the woman are the twin pillars of bourgeois morality’.

Hedda says to Brack ‘I’m content so long as you don’t have any sort of hold over me, subject to your will and your demands. No longer free! That’s a thought that I’ll never endure’. Emma Goldman wrote ‘true emancipation begins neither at the polls nor in the courts. It begins in woman’s soul’ although Eleanor Marx wrote of women ‘that the question is one of economics. The position of women rests, as everything in our complex modern society rests, on an economic basis’.

Hedda is an existential heroine in the sense of ‘Vivre ? les serviteurs feront cela pour nous’ (‘Living ? Our servants will do that for us’) from Axël by Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam. Brack is enamoured of Hedda’s feminine strength but fears her advocacy of what Nietzsche described as ‘to live dangerously’ and does not understand Hedda’s views on Lovborg’s suicide; ‘there is beauty in this deed, an act of spontaneous courage to take his leave of life so early’. This is reminiscent of Nietzsche’s dictum ‘voluntary death that comes to me because I wish it’. However Hedda cannot meet Nietzsche’s idea of ‘amor fati’, the ultimate affirmation of life and instead accepts a terrifying nihilism.

In socialism Engels wrote ‘what will most definitely disappear from monogamy, first, the dominance of man, and secondly, the indissolubility of marriage’. Eleanor Marx concluded that ‘the woman will no longer be the man’s slave but his equal’.