Book Review: ‘The Best of Pearse’

Patrick Pearse

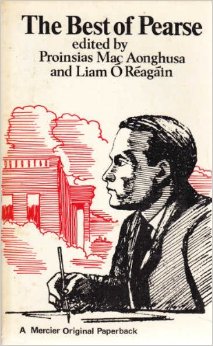

‘The Best of Pearse’, edited by Proinsias Mac Aonghusa and Liam O Reagain. The Mercier Press, Cork, 10s.

This book is a collection of the writings of Patrick H. Pearse who was executed by the military representatives of the British ruling class after the collapse of what has come to be known as the Easter Rising, in Dublin in 1916.

This book is a collection of the writings of Patrick H. Pearse who was executed by the military representatives of the British ruling class after the collapse of what has come to be known as the Easter Rising, in Dublin in 1916.

Pearse practised at the Bar for a brief period and is reputed to have originated the IRA tactic of refusing to recognise British Courts. Useful though such heroics, and their inevitable tactical offsprings, proved to the British Authorities (and later the N. Ireland and Eire governments) in creating “gaol battalions” of the IRA, it is not for this that Pearse is remembered.

Nor is his claim to fame to be found in his writings as a teacher and educationalist (some of which are found in this collection) though, in the latter capacity, he proved capable of observing the perverted purpose of education in the hands of the State—albeit that the “State” for Pearse was the English State and not the state of capitalism.

Pearse’s real claim to a place in Irish history was his execution by the British military after the abortive 1916 Rising. Also executed were the six other members of the Provisional Government of the proclaimed Republic, among whom was James Connolly.

Connolly (and the digression is deliberate) was a former member of the British Social Democratic Federation and was prominent in the maelstrom of controversy that shook that organisation immediately after the turn of the century. Out of that controversy was born the first of the Companion Socialist Parties (the Socialist Party of Gt. Britain) and the almost defunct Socialist Labour Party, of which Connolly was a prominent member.

Among “left-wing” organisations in Ireland and similar organisations of Irish emigrants in Britain the name of Connolly is revered as the “Lenin of Irish Socialism”. Despite the fact that Irish Capitalism, in the post-Connolly era, did not develop Russia style, the analogy is a good one—insofar as both Lenin and Connolly made effective contributions to the confusion of the working class by overlaying the simple case for Socialism with complex issues of concern only to the nebulous interests of capitalism in their respective countries. Since Connolly’s contribution in this respect was almost exclusively restricted to Ireland, where it is linked with the rabid nationalism of Pearse, we felt that somewhere in these writings we might unscramble the mystery of their association.

Apart from an insipid playlet and some mediocre poetry the collection contains a number of essays, often repetitive, in which Pearse deals with Nationalism, Education, Literature and Freedom. In a style reminiscent of the later ‘heroes’ of Hitler’s National ‘Socialism’ he declares his faith thus: The Irish political leaders “have conceived of nationality as a material thing whereas it is a spiritual thing. They have made the same mistake that a man would make if he were to forget his immortal soul. They have not recognised in their people the image and likeness of God. Hence the nation to them is not holy . . . a thing so sacred that it may not be bought in the market places at all or spoken of where men traffic.”

Here, as with Connolly, is the failure to recognise that the very thing he edifies, the national state, is the political creature of that system whose effects he vilifies, capitalism. Again, in dealing with Freedom and Education, Pearse proves himself an observant reporter of effects but wholly off-course when it comes to cause. Thus, in The Murder Machine he imputes to the “English education system in Ireland” the fact that:

“The modern school is a State-controlled institution designed to produce workers for the State.”

and he quotes Professor Eoin Mac. Neill in comparing the same “English system in Ireland” with “slave education” designed not to make children “strong, proud and valiant, but to be sleek, to be obsequious, to be dexterous . . . to make them good slaves.”

The fact that the “English system of education” in Ireland was the same as it was in England, or anywhere else in the world of capitalism, a system designed to equip working class children for their adult role of wage slaves, was missed as was recognition of the fact that the great majority of “the English” had as little freedom and prosperity as their Irish counterparts. That, in fact, the common enemy of the great majority of Englishmen and Irishmen was the system of international capitalism.

As we struggled through this windy prose we were tempted to wonder what was Connolly’s reaction to Pearse’s naive outpourings and then we remembered that his reaction was to become Pearse’s comrade-in-arms.

The Best of Pearse is artless, ignorant and its presumption to wit, monotonous—except, perhaps, when Pearse feels “sure that political economy was not invented by Adam Smith but by the devil”!

Richard Montague