Book Review: ‘The Prophet Outcast’

More about Trotsky

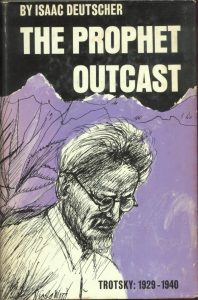

‘The Prophet Outcast’, by Isaac Deutscher, Oxford University Press, 45s.

This is the last of the three volumes of Deutscher’s magnum opus – the biography of his hero Leon Trotsky.

This is the last of the three volumes of Deutscher’s magnum opus – the biography of his hero Leon Trotsky.

It is not likely that many members of the working class of our affluent society will be able to afford to buy it. Nor, in truth, is a great deal of its bulk (nearly 500 pages) worth ploughing through. Much of its value is of a rather negative kind, demonstrating the type of thought and action we should avoid. And, willy nilly, the author tells us at least as much about his own mental processes as a “Trotskyist” (the inverted commas are essential; one is no surer at the end than at the beginning what kind of an animal a Trotskyist is) as about the career of his subject.

The book takes us from the banishment of Trotsky from Russia by Stalin in 1929 to his butchery (the phrase is literal enough; the end was achieved with an ice-axe) by a Stalinist thug in 1940. It consists of a record of his life in the various countries of his refuge (Turkey, Norway, France and Mexico) and of his personal and family hardships and tragedies, which were indeed many and moving. At the same time, it recounts the story of his political and action during those eventful years. It is, of course, with these that we are mainly concerned here.

Immediately, we are up against the negative aspect of the whole Trotsky saga. The first thing any student of politics would like to know is: what was the real difference that divided the hero of this book from the villain? What profound principle formed the basis of the murderous feud between these two men, both of whom called themselves communists? Well, here is one reviewer at least who is no wiser now that when he started.

On the contrary, time and again we find that on issues which appear to be really burning matters like the forced collectivisation of the peasants, for example, fierce invective against Stalin for doing the opposite of what Trotsky in exile advocated, is followed by bitter criticism of Stalin for in due course altering his tactics and doing the very thing that Trotsky advocated. As usual among politicians this leads not to gratification but to sour frustration and accusations of stealing clothing (or thunder, as the case may be).

How familiar all this is to us in England; and how excruciatingly boring. How often have we heard the Labour Party moan that all its best policies are pinched by the wicked Tories? It never seems to occur to them that either way the masses they are supposed to represent are going to get the “benefit” of the policies they claim will be so good for them. Nowhere in this book do we get the slightest hint that either Trotsky himself, or Deutscher, or any other of the characters that flit across the pages has the faintest realisation that there must be something odd about their policies if a monster like Stalin can adopt them, even tardily. And, above all, if the result of this adoption left all the evils of capitalist society as prevalent in Russia as they could be.

Trotsky was undoubtedly a man of considerable intellectual capacity. The author proudly tells us at the end that a post-mortem on his hero’s brain necessitated by the murderous smashing of his skull, revealed a brain weighing two pounds and thirteen ounces, which is apparently very much larger than normal. His ability is revealed all through the book in copious quotations from his writings. And it is impossible to dispute the fact that Deutscher, too, has a brain of some weight. But what does all this amount to? For practical purposes, it all adds up to nothing of any moment at all.

One searches in vain for some sort of focus to find out what all the fire and fury was about. In all the thousands of words not a word to tell us what is this “communism” that the two great protagonists were supposed to be fighting about. On the contrary, it is made abundantly clear that both sides agreed that State capitalism was Socialism. And Deutscher makes no secret of the fact that he, too, is satisfied to swallow and indeed to propagate this flagrant contradiction.

On page 55, for example, he makes it clear that he agrees with Trotsky that the working class in Russia cannot be exploited because there is no class which owns the means of production. He apparently does not even begin to see the truth of the matter which is that the Russian worker has to get up to the sound of a similar alarm clock as wakes his British counterpart, and do his stint by the day or the week for a wage which will enable him to keep himself and his family until the next wage comes along. That his only choice is to do that or starve. And that, as the fruits of his labour are removed from him in the same way as they are here, then someone must be enjoying the fruits of that exploitation.

Instead, Deutscher blinds himself with talk about power being in the hands of the proletariat—without, of course, a tittle of evidence to show that this is anything other than a grotesque fraud and that the proletariat in Russia is as powerless as in England; more so in fact, since it has not even the power of a free vote in a semblance of a democracy.

It is as a result of such a basic misconception that we get episodes which are merely farcical, but to Deutscher are intensely puzzling—such as the difference between groups of Trotskyists as to whether they should support Russia or China over the possession of the Manchurian Railway. Or, still more breathtaking, the spectacle of Trotsky supporting the treacherous grabbing by Stalin (by arrangement with Hitler) of Eastern Poland and the Baltic States because the local capitalists were thereby expropriated. It never seems to occur to these intellects that whenever the workers of such countries get a chance to show what they think of their “improved” position as a result of such happenings, they vote with their feet by the hundred thousand so that the communists have to build walls and barbed wire fences to keep the faithless ones in their compulsory heaven.

Running through this book like a grisly thread is the story of the terrible purges which Stalin was perpetrating in this period, and which indeed went on long after Trotsky’s death. Trotsky’s friends and his children were, of course, among the prominent victims of this appalling holocaust and it is impossible not to feel profoundly moved by his sufferings, even though one is ever conscious of the fact that the basic philosophy of it all, the reign of terror and the slogan that “the end justifies the means,” was born of the basic flaw which we exposed right back in 1917—namely, the theory that a small clique of elite communists can capture power for the purpose of giving Socialism to a non-socialist working class. Trotsky himself was one of the arch-perpetrators of the Bolshevik reign of terror and he himself must have been haunted by the ghosts of those who he had sent to their doom.

The purge trials, in which Stalin staged the judicial murder of all the famous old Bolsheviks he could lay his hands on, may seem like a dim and distant history to most people, but some of the names in the book make one realise that it is all not so long ago and that there are still people very much with us in England today whose attitude while the murders were actually being committed was to justify them. Trotsky complains bitterly, for example, about the equivocal attitude of Kingsley Martin who was the editor of the New Statesman in those days and who defended the stand taken by the then Labour M.P. and barrister D. N. Pritt, Q.C., the man who appointed himself the apologist-in-chief in this country for Stalin’s murders. The former would no doubt like to forget, but Pritt is still being trotted out by the communists here at their rallies and it really is quite eerie to see, as large as life and as brazen as ever, one who insisted that the confessions were genuine of people who are being resuscitated (though not revivified) by Stalin’s former accomplice Khrushchev.

But one turns quickly from such people to Deutscher himself. And here we must find room to single out one case which throws a lurid light on the whole dreadful business and on the attitude of Trotskyists and Stalinists alike, the case of Krestinsky, a former Soviet Foreign Minister. This leading Trotskyist did something that apparently nobody else did in all those fearful years; he retracted in open court and in the presence of foreign journalists the confessions that he had made to the secret police. The sensation this made at the time can well be imagined and, of course, this very episode gives the lie to all those apologists who said that the unanimity of the confessions made them beyond reproach. What happened as a result of Krestinsky’s avowal that his confessions had been extorted from him by the police? The judge, instead of ordering a full enquiry into all the facts, hurriedly adjourned the proceedings. And next day, after a night in the hands of his tormentors, Krestinsky came back into court and retracted his complaint about extortion.

This one instance threw the whole thing into the open and Krestinsky’s heroism was plain for all to see—as well as its tragic futility. But although one does not expect anything from the apologists of the time, what of Deutscher, who would presumably have saluted this gallantry in the part of his fellow-Trotskyist? He refers to Krestinsky’s gesture as “feeble.” This is written now, long after the revelations of the Khrushchev “secret” speech in which he made it clear that Stalin extracted his confessions by barbaric torture. And to add to the dreadful irony of it all, one reads in a recent issue of the New Statesman an article, by this same Deutscher, in which he mentions that Khrushchev has just “rehabilitated” Krestinsky as innocent of the crimes for which he was hanged and whose confession was the basis of the charges for which Bukharin and Rykov and so many others were hanged with him. Incidentally, this is, we believe, the first case of a prominent Trotskyist leader being exculpated. If the masters of Moscow get round to rehabilitating the arch-enemy Trotsky himself, then our tame communists will really have some words to eat.

L. E. Weidberg