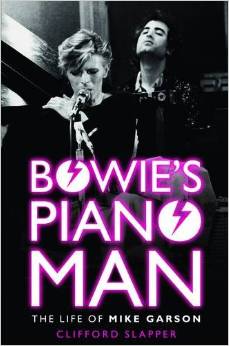

Mixed Media: Bowie’s Piano Man

Bowie’s Piano Man: The Life of Mike Garson by Clifford Slapper is a musical biography of the avant-garde jazz pianist who has worked with David Bowie over the last forty years.

Garson came of age musically in the 1960s when people would ‘listen to Bartok, John Coltrane and Jimi Hendrix all in the same day’, and he had his big break in 1965 in Greenwich Village when Elvin Jones, renowned drummer with John Coltrane called on Garson to replace a pianist. Slapper describes the influences of jazz pianists Cecil Taylor, Erroll Garner, Herbie Hancock, and Bill Evans on the young Garson. Jim Merod concluded that Garson is ‘within the circle of genuinely masterful jazz pianists including Bill Evans, Art Tatum and Thelonius Monk.’

Garson came of age musically in the 1960s when people would ‘listen to Bartok, John Coltrane and Jimi Hendrix all in the same day’, and he had his big break in 1965 in Greenwich Village when Elvin Jones, renowned drummer with John Coltrane called on Garson to replace a pianist. Slapper describes the influences of jazz pianists Cecil Taylor, Erroll Garner, Herbie Hancock, and Bill Evans on the young Garson. Jim Merod concluded that Garson is ‘within the circle of genuinely masterful jazz pianists including Bill Evans, Art Tatum and Thelonius Monk.’

Slapper details Garson’s work with Bowie beginning with the 1973 album Aladdin Sane, which he expressively describes as ‘the arrival of Aladdin Sane was the 1970s equivalent of joining the first passenger jet into space.’ The album lyrics describe New York City’s urban decay, decadence, drug addiction, violence and death just prior to some catastrophe. Garson’s piano parts on Aladdin Sane are exquisitely beautiful cascading notes. Nicholas Pegg wrote that ‘Garson’s breathtaking jazz/blues inflections forcibly steer away from pure rock’n’roll, creating a vigorous hybrid somewhere between the Stones and Kurt Weill.’ The song Time is Brechtian Cabaret, and it is interesting to compare with the cabaret music of Jacques Brel and Weimar Marxists Brecht-Weill. Garson used the old stride piano style from the 1920s which ‘sounds like those old-fashioned rinky-tink bar-room pianos.’ There are a number of links between Brecht-Weill and Bowie-Garson; Brecht-Weill’s Alabama Song was recorded by Bowie in 1978, Bowie had the title role in the 1982 BBC TV dramatisation of Brecht’s Baal, and at his father’s funeral at his request Garson played Weill’s September Song and Brecht-Weill’s Mack the Knife.

Garson’s sweeping piano runs were a key feature on the songs We are the Dead, 1984, and Big Brother on Bowie’s 1974 album Diamond Dogs which was based on George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty Four. The lyrics describe a dystopian post-apocalypse nightmare, and highlight Bowie’s political anxieties about leadership, submission to authority and conformist beliefs. Bowie later said it was an ‘apocalyptic kind of view of our city life… it just coincided with the first economic disasters in New York.’ Allan Tannenbaum’s New York in the 70s describes how ‘economic stagnation coupled with inflation created a sense of malaise’, in 1975 New York City was on the verge of bankruptcy, then AIDS devastated the gay and artistic community (see Larry Kramer’s Reports from the Holocaust.)

Garson was a Scientologist in the 1970s but Slapper does not elaborate on Bowie’s 1997 Q magazine interview where he says Scientology had caused ‘one or two problems’, although Garson does say he ‘went through a period of being overbearing in his attempts to persuade others to take an interest in his spiritual beliefs.’ David Buckley wrote that Garson’s ‘ proselytising efforts had converted both Trevor Bolder and Woody Woodmansey’, and D’Agostino in Glam Musik quotes Bowie: ‘He tried it on with me a bit until we had a fight about it. He was so po-faced. Very serious guy. We used to call him Garson the Parson.’ William S Burroughs believed that Scientology might help where psychoanalysis had failed, and that auditing techniques could do more in ten hours than psychoanalysis could do in ten years but he was ‘disgusted by the authoritarian organisation and the stupidly fascistic utterances of L Ron Hubbard. The aim of Scientology, complete freedom from past conditioning, was perverted to become a new form of conditioning. He had hoped to find a method of personal emancipation and had found another Control System. It was like a State, with its own courts and own police’ (Literary Outlaw, Ted Morgan)

Garson ‘has a lot of faith in humanity and the goodness of human nature’, and the need to spread the idea of connecting to something bigger and deeper through an exploration of artistic creation. Garson says ‘everybody is innately connected to God, and is God’, and ‘We are indeed all deeply interconnected’ which evokes Jung’s ‘collective unconscious.’ Garson, and Slapper to some extent, appear to have sympathy for the Jungian concept of ‘synchronicity.’

Garson ‘has a lot of faith in humanity and the goodness of human nature’, and the need to spread the idea of connecting to something bigger and deeper through an exploration of artistic creation. Garson says ‘everybody is innately connected to God, and is God’, and ‘We are indeed all deeply interconnected’ which evokes Jung’s ‘collective unconscious.’ Garson, and Slapper to some extent, appear to have sympathy for the Jungian concept of ‘synchronicity.’

Garson’s spirituality can find echoes in Erich Fromm’s Marx’s Concept of Man: ‘For Spinoza, Goethe, Hegel, as well as for Marx, man is alive only inasmuch as he is productive, inasmuch as he grasps the world outside of himself in the act of expressing his own specific human powers, and of grasping the world with these powers. In this productive process, man realizes his own essence, which in theological language is nothing other than his return to God.’

Garson sees creative artists ‘projecting what the future society is supposed to be’, and the positive social significance of art and creativity which we see in William Morris’s Art, Labour and Socialism. Slapper writes ‘there is plenty of evidence showing how the human brain is capable of great cooperation and collective creativity. Every performance by every orchestra bears testimony to this.’

Bowie’s Piano Man is a welcome addition to my bookshelf and sits between the bookends of The Complete David Bowie by Nicholas Pegg, and Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story by David Buckley.

Bowie’s Piano Man can be ordered at www.fantomfilms.co.uk/books/cliffordslapper_mikegarson.htm

STEVE CLAYTON