Book Reviews: ‘A Darwinian Left’, ‘Marx in Soho’, & ‘Against Parliament – For Anarchism’

A Darwinian Left

‘A Darwinian Left: Politics, Evolution and Co-operation’. By Peter Singer, Wiedenfeld & Nicholson.

This book is based on the mistaken assumption that Socialists are not Darwinians. Right from the start, Socialists embraced Darwin’s theory of the evolution of species through natural selection, and propagated it in the face of religious obscurantism. Indeed, a number of well-known early Marxists came to socialism through Darwinism, Karl Kautsky in Austria and Edward Aveling in England for instance.

What Singer has done is to accept the hi-jacking of the terms “Darwinian” and “Darwinism” by rightwing ideologists who see both nature and human societies as involving a competitive struggle for survival between selfish individualists. Singer does concede that Socialists accept Darwin’s theory, but criticises us for refusing to extend it from nature to human societies. Socialists do indeed say this (after all, Darwin only claimed to be a biologist, not a sociologist) and have been saying it for a hundred years now, ever since we had to confront the “Social Darwinists” of the turn of the last century who used Darwin’s theory to justify the rugged individualism of US capitalism during the age of the Robber Barons. Typical of such people today are the editors of the series of which this book is one, “Darwin@LSE”.

The argument between Socialists and such people is not about the validity of Darwin’s theory of evolution but about the evolved biological nature of humans. Are humans an animal whose biologically-evolved brain allows them to adopt a great variety of different behaviours depending on the social and physical conditions they were brought up in or is there something in their biological makeup that restricts their behaviour within a relatively narrow range which Singer lists as “greed, egoism, personal ambition and envy that a Darwinian might see as inevitable aspects of our nature”?

Certainly, humans can and do exhibit these traits, but the question is: are they innate and are humans capable of behaving in other ways too (answer: yes, of course they are)? Also, the view that the main feature of human biological nature is behavioural versatility and flexibility is no less Darwinian than the opposite view. It is in fact the more accurate, given the evidence accumulated to date by anthropologists, geneticists and neuroscientists.

Although we don’t like the term a “Darwinian Left” exists and has done for over a hundred years, arguing that humans are a biologically-evolved species whose behaviour is socially, and no longer biologically, determined and that the societies which groups of humans live in evolve on a quite different basis from that of the evolution of biological species. For a start, it is a key principle of Darwinism that acquired characteristics cannot be inherited; that was the view of Lamarck which Darwinism replaced. When it comes to social and technological evolution, however, Lamarck rides again: acquired characteristics can be passed on, by non-biological means of course; which is why such evolution is much more rapid than Darwinian biological evolution, and why in fact humans have had to adapt to many different types of societies since we first evolved without our biological nature changing hardly at all. Fortunately, that nature includes precisely the capacity to adapt to different social environments.

What Singer is seeking to be is a leftwing biological determinist, a leftwing Social Darwinist. Singer, however, is not a socialist but a reformist—his hobby horse is that animals have abstract “rights” and that this should be enshrined in law—so has no problem seeing himself as the leftwing of an essentially anti-socialist ideology.

ALB

************************************************************

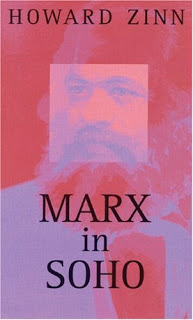

Marx in Soho

‘Marx in Soho’, by Howard Zinn. (South End Press, distributed by Pluto Press)

Granted his request to return to earth for just one hour, to clear his name and refute the rumour that his ideas are dead, a bureaucratic mix-up finds Karl Marx in Soho, New York, instead of Soho, London where he once lived.

Granted his request to return to earth for just one hour, to clear his name and refute the rumour that his ideas are dead, a bureaucratic mix-up finds Karl Marx in Soho, New York, instead of Soho, London where he once lived.

This short, one-man play sees Marx alone on stage, with only a table, a chair, books, newspapers and a glass of beer as props, reminiscing about his family life, enthusing about the Paris Commune and reliving an imaginary confrontation with the “shaggy anarchist” Bakunin.

Zinn’s Marx can be humorous one page, and deadly serious the next in vitriolic condemnation of a system he spent his life trying to overthrow. One moment Marx is recounting his countless journeys home from the British Museum, past open sewers telling how it was “only fitting that the author of Das Kapital should slog through shit while writing the condemnation of the capitalist system”. The next he is grappling on the floor with a drunken Bakunin. Then, just as suddenly, we can hear the bearded man launch a vehement attack upon the notion that the Soviet Union was socialist: “Do they think that a system run by a thug who murdered his fellow revolutionaries is communism? Scheisskopfen . . . can that be the communism I gave my life for? . . . Angry. . . Socialism is not supposed to reproduce the stupidities of capitalism!”

For anyone coming into contact with Marx’s ideas for the first time, dreading the thought of long, studious hours in front of volumes of insipid texts on political economy, having only ever heard second-hand, distorted accounts of Marx’s theories, fear not; this is a welcome first point of reference in which Zinn makes his ideas accessible and the man himself, less the spectre that haunted Europe, than some 19th century alternative comedian who just happens to know what capitalism is really all about.

The Labour Theory of Value, the Materialist Conception of History and the Class Struggle are all Marxian ideas that get aired in this short work, as well as concepts such as nationalism and alienation.

And one thing is certain; Marx in Soho is not just Marx speaking. Zinn is very much in agreement with Marx. When Marx, despairing at the consumer culture that has evolved says; “Doesn’t anyone read history? . . . what kind of shit do they teach in the schools these days?” this is the real Zinn speaking, the Zinn whose books such as A People’s History of the United States, are proscribed in US schools.

His hour up, Marx is about to leave the stage but stops and turns. “Do you resent my coming back and irritating you?” he asks. “Look at it this way. Christ couldn’t make it, so Marx came.”

It’s been an hour well spent. Marx is vindicated. His theories are still relevant. Socialism is not dead—it was never tried. The philosophers are still interpreting the world, whilst the point is still to change it.

JB

************************************************************

Anti-parliamentary dogmatism

‘Against Parliament. For Anarchism’. Pamphlet by the Anarchist Federation.

This latest offering from the Anarchist Federation (formally known as the Anarchist Communist Federation) once again re-affirms their position that the revolutionary process towards “anarchist communism” can and must in no way involve the use of parliament. Indeed, the pamphlet itself is comprised of a discussion of the main political parties in Britain (including a chapter on the far left and right), all of whom advocate the use of parliament to advance their political programmes.

Unfortunately, the AF did not feel it necessary to mention the Socialist Party which is a shame as we are well-known to the AF and although not part of the same milieu, members of both organisations have been able to strike up cordial relations on occasion. The reason for this is that the AF’s definition of “anarchist communist” society is almost indistinguishable from our view of socialism, i.e. moneyless, stateless with free access to goods and services. Perhaps, the main bone of contention is how we get there and here there are some real differences.

Whereas we emphasis mass democratic political action by a majority of the global working class (which may well involve socialist delegates being sent to parliaments) as the best means for attaining world socialism, the AF see the revolutionary process more in terms of community/worker resistance and mass action through strikes and riots and the like. However, some of their views seem remarkably similar to those of the Socialist Party’s:

“Anarchist communism would depend on mass involvement. This is both to release everyone’s inventiveness and ideas and to prevent the formation of some sort of elite. Two forms of organisation are crucial in this context. The first is regular mass meetings of communities and workers, to ensure that full discussion and participation in matters affecting a locality could be achieved. The second is federation, as many issues need a broader perspective than the local. Federalism would run through successive bands—local, district, regional, international—to take decisions appropriate to that band” (p.54).

Needless to say that the AF’s vision of a new society is far more edifying than the oxymoronic Trotskyist notion of a “workers’ state” (state capitalist nightmare), but their anti-parliamentary dogmatism means that the question of the state in a revolutionary situation is effectively ignored.

No-one can be exactly sure which form the revolutionary process will take and it may well involve some of the things the AF point to. However, we in the Socialist Party believe that the potential use of parliament as part of a revolutionary process may prove vitally important in neutralising the ruling class’s hold on state power. For us, this is the most effective way of abolishing the state and thus ushering in the revolutionary society.

The pamphlet itself is not a bad read (for a quid) and is especially interesting for budding political anoraks who wish to differentiate between the “National Democrats” and the National Front or the Scottish Socialist Party from the Socialist Workers Party. This said, it is more descriptive than analytical and the AF are wrong—even slightly disingenuous—to mix up the parliamentary reformism of the Trotskyists without reference to the revolutionary approach of the Socialist Party.

DAVE FLYNN