Book Review: ‘Double Jeopardy – The Retrial of the Guildford Four’

Double Jeopardy

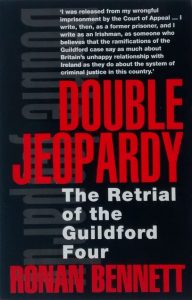

‘Double Jeopardy: The Retrial of the Guildford Four’, by Ronan Bennett. (Penguin Books £4.95)

On 5 October 1974, history, prodded by events in Northern Ireland and served by an IRA gang, visited Guildford. Bombs were left in two public houses and seven people were murdered and ten times that number injured.

On 5 October 1974, history, prodded by events in Northern Ireland and served by an IRA gang, visited Guildford. Bombs were left in two public houses and seven people were murdered and ten times that number injured.

The anger of the bombers was reciprocated in the subsequent thuggery of the police, in the frame-up of three innocent men and one innocent woman all signally undistinguished in any ability to defend themselves, in a remarkably incurious judge and a jury of people who knew that British justice does not make mistakes.

But British justice had made yet another mistake and, after that, the mistakes kept happening and they were generally facilitated by the Labour Party’s anti-Irish Prevention of Terrorism Act. But the police had been too undiscriminating, too anxious for convictions and their choice of victims were so lacking in any vestige of reality that questions were bound to arise.

Anyone familiar with IRA organization knows that “hoods” (IRA-speak for ordinary criminals) are not, for obvious reasons, welcome in the organization. One of the Guildford Four, Conlon, in his book, Proved Innocent, admits that he and Paul Hill were involved in petty crime, heavy drinking and drugs. Judith Ward lived in a world of drug-induced make-believe and Armstrong, whose confession started the ball rolling, is described by Bennett thus:

“By his own admission he was at the time a habitual drug-user, taking anything and everything he could lay his hands on. He lived with motley crews in squats and abandoned houses in the Kilburn-Cricklewood area, he signed on, he shoplifted from supermarkets and fantasized with his friends about ‘big scores’.”

If the police and the judiciary were prepared to see these unlikely characters as IRA bombers many others were sceptical and a number of people who knew their way around started looking at the police case. The upshot was that after nearly fifteen years in prison, the Guildford Four, like the Maguire Seven and the Birmingham Six, were exonerated. They had won a famous victory over British Injustice!

The be-wigged fraternity who administer the rules of British capitalism were not amused. Bennett argues that senior figures in the judiciary relayed comment about the guilt of the Four on a lobby basis. Some, like the Recorder of London, Sir James Meskim, voiced his bitterness, inferring that the Four were really guilty, but, after a newspaper article claimed that some of the Four were going to sue, he retracted his statement.

Lord Denning, paragon of the British legal system, revealed the arrogance and bitterness that lay under his wig when he told the Spectator that it would have been better of the Birmingham Six had been hanged so as to avoid damaging campaigns on behalf of plainly guilty men. It was the attempt by British justice to retrieve the situation through indirectly re-indicting the Guildford Four that is the substance of this book. Bennett, with skill and insight, reveals a squalid conspiracy of legal eagles, journalistic liars and the police to tailor the finding of a subsequent trial of three of the many police officers who were instrumental in kitting out the Guildford Four so as to make it appear that the Four were guilty.

Socialists have no illusions whatsoever about the justice enshrined in the code of rules needed to run a system based on theft and exploitation. But Bennett’s exposition of this particular legal scam is an interesting read and one that shows that, in court, scoundrels are not confined to the dock.

Richard Montague