Tito and Balkan Capitalism

The truth behind the crocodile tears

Josif Tito, President of Yugoslavia, died on May 4, 1980. The media commentators dug out the cringing cliches that they use to describe the despots of foreign states that are (actually or potentially) the allies of British capitalism. The editor of The Times, William Rees-Mogg, said in a leading article (5/5/80) that Tito was “a man of extraordinary stature”, and that he “belonged among the great men of his time”; the whole-page obituary in the same paper said he was “perhaps one of the few remaining idealists”, and so on. Reporting his funeral, Keith Graves on the BBC news (8/5/80) said “this was the day when the world mourned” (did you mourn, dear reader?) and Sue Lawley, on Nationwide (8/5/80) said Tito had “brought brotherhood and freedom to a divided nation”. The pundits could not have been more servile if he had owned an oil-field. But these comments belong in the fantasy world of highly-paid journalists and broadcasters: they have no connection with the facts.

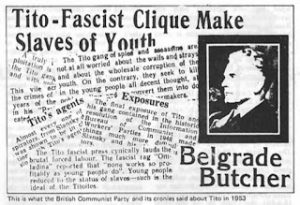

In reality Tito was a remorseless ruffian, an implacable hatchet-man, who rose to power by jailing and killing potential rivals, and who then lived in ostentatious luxury as front man for the Yugoslav ruling class while the workers toiled m poverty to produce the good things that the Yugoslav upper class enjoyed. A tyrannical dictator of Tito’s stamp would be attacked without mercy by the British media if he was an enemy of the British ruling class; as a thorn in the side of Russia, he was, and is, glorified.

A glance at the historical background is necessary to understand Yugoslavia, its relations with other countries, and the internal and external strains that threw up such bully-boys as Tito. As capitalism established itself in south-eastern Europe during the nineteenth century the existing political divisions (that is the Russian, Austro-Hungarian and Turkish empires, all dating from an era when the landed aristocracy had held the power) became increasingly out-of-date. Capitalism needed new political structures, and the “nation-state” was in much of south-eastern Europe the chosen vehicle. The idea behind these so-called nation-states- that homogeneous “nations” of convenient size, with one language, one culture and united economic and social interests, occupy neatly-divided sections of the earth’s surface has always been an illusion. The Albanians, for example: they speak two dialects so divergent that they should be regarded as two languages rather than one; they do not by any means all dwell in what is called Albania—many are scattered across the Balkans, others live (and have lived 600 years and more) in southern Italy; and among those speaking Albanian languages live others speaking other languages. However, capitalism has forced us to swallow greater illusions than that. So an entity called “Albania” was created in part of the old Turkish empire, with an Albanian national anthem, Albanian armed forces and history-books full of Albanian patriotism: all based on the class-division of capitalism—the many, poor, labouring, and ready to die for the (newly designed) flag and the few, prosperous, leisured, and ready to let them. It would have been a farce if it were not so tragic, and it was paralleled throughout the Balkans.

Motley people

The earlier empires creaked and groaned under the stresses of the First World War, and two of them (the Austro-Hungarian and the Turkish) collapsed entirely while the third, the Russian, survived only under entirely new management. But the reorganisation of the Russian empire, as capitalism established its political power there, meant that for twenty years after 1917 Russia had to concentrate on internal affairs and postpone its previous steady advance across Eastern Europe.

East of the Adriatic, between Italy and Albania, was a heterogeneous collection of people, languages and religions (Roman Catholic, Greek Orthodox and Moslem) — the Slovenes in the north, the Croats around Zagreb to their south, the Dalmatians on the coast, the people of Slavonia further east, the Bosnians, Herzegovinians, Serbians, Montenegrins, Macedonians, and so on. Most of them spoke Slav languages, and most were too few to populate a state suitable for independent capitalism on their own. so they were all lumped together, willy-nilly. Some were less willing than others: the Montenegrins, who had already had a brief existence in a separate state before the war; the Macedonians, who wanted to join up with other Macedonians in Greece and Bulgaria, and the Croats, who feared the Serbs would swamp them. Serbs and Croats spoke dialects of the same language, but had been divided by their separate and antagonistic histories—the Serbs had the Cyrillic alphabet and the Eastern Orthodox church, the Croats had the Latin alphabet and the Roman Catholic church. In among this already motley collection of mainly Slav peoples were many Hungarians and Albanians, with sizable populations of Turks, Rumanians, Gypsies, Slovaks, Bulgarians, Germans, Ruthenians, Czechs and Italians, as well as smaller groups of Poles, Austrians, Greeks and Jews. Capitalism forced all these people together in one discordant mass, and called the concoction the Kingdom of the South Slavs, or Yugoslavia. The King of Serbia, Peter Karageorgevitch, became King of Yugoslavia.

Yugoslavia and the other Balkan states created or confirmed in 1918 were always shaky, lacking the morale-boosting propaganda advantages of a long history and furthermore Russia, though still pre-occupied with establishing state capitalism, never ceased to cast its eyes covetously at eastern Europe. The Balkan countries became increasingly autocratic. King Alexander, Peter’s son, overthrew the democratic constitution and became a dictator in 1929. The rumbling discontent (and sometimes more than rumbling — Alexander was assassinated by a Croat dissident on a visit to Marseilles in 1934) was all to Russia’s advantage. The Russians organised underground parties of the discontented in all the eastern European states (as well as elsewhere) in the 1920s and 1930s, using, as many other capitalist states before had done, revolutionary language to cloak expansionist aims. The Yugoslav “Communist Party” was formed in 1919, although of course it had nothing whatever to do with Communism. One of its members was Josif Broz, later known as Tito.

Russia’s puppet

Broz was born in 1892 near Zagreb, then in the Austro-Hungarian empire. As a young man he worked in a car factory near Vienna, then joined the Austrian army and was captured in Russia during the First World War. When the 1917 revolution broke out Broz became a Bolshevik and served for three years in the Russian army. Returning to Yugoslavia, he worked for the Russian-inspired underground (the “Communist Party” was banned in 1921). In this puppet party of the Russian Bolsheviks Broz worked hard (or his Russian masters. As Zagreb branch secretary he denounced the Yugoslav leadership to the Comintern (the Russian-led international organisation of Bolshevik-style parties) and the old central committee was sacked wholesale by the Russians, and a new one appointed which would be more loyal to Russia. After this success, Broz was arrested and jailed for five years by the then Yugoslav dictatorship. Emerging in 1934, he became a member of the Yugoslav party’s central committee, and began installing in influential party positions members devoted to himself (much as Stalin had done in Russia in the early 1920s). Then he left for Moscow as Yugoslav link-man with the Comintern.

In 1936 disloyalty to Stalin and Russia was again rearing its head in the Yugoslav party. The whole of the Yugoslav politburo was called to Moscow and dismissed from office. The loyal Stalinist Broz became organisational secretary. In 1937 the Yugoslav party secretary, Milan Gorkic, was arrested; he and most of the other Yugoslav party leaders were jailed and executed by Stalin. Broz was Stalin’s close collaborator in this sweeping slaughter, and ascended over the bodies of his dead colleagues to the leadership of the Yugoslav Stalinist party. In 1938 he returned to Yugoslavia as Stalin’s trusted emissary. He advanced men he could rely on to positions of power, and purged those not slavishly obsequious to Stalin and himself.

The war

The war came, and Yugoslavia was occupied by the Germans. When Russia entered the war, Broz (or Tito) loyally called for an insurrection against the German occupation forces, with the immediate aim of helping the Russians, and to pave the way for a Stalinist takeover of Yugoslavia after the war. The Yugoslav royalist government, in exile in London, had also organised clandestine warfare against the Germans under General Mihailovitch, so that they should have armed forces in the country ready to seize power again after the war. The two sets of terrorists, or freedom-fighters (the nomenclature depends on one’s political convictions) fought against each other as much as against the Germans. The same was happening in other east European states, which suited neither Russia nor the Anglo-American allies. The British and Americans wrote off most of the Balkans as being Stalin’s reward for fighting the war, but insisted on Greece remaining as an Anglo-American client state.

So Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt came to an agreement at the Tehran Conference of 1943. The British and Americans would abandon Mihailovitch and the other “right-wing” guerillas of eastern Europe, while Stalin promised to abandon the Stalinist partisans of Greece. Henceforward in Greece only the anti-Stalinists, and in Yugoslavia only the Stalinists, got military aid from the Allies. So when Germany collapsed in 1945, Tito was able to smash all opposition—Mihailovitch was captured and executed, and Archbishop Stepinac, leader of the Yugoslav Catholic Church, sent to jail—and establish a Stalinist dictatorship. In the same way the government of “liberated” Greece, backed by the Anglo-Americans, was able to smash the Stalinist organisations EAM and ELAS, while Russia, keeping its promise, stood by with folded arms.

Many of those who fought under Mihailovitch against the Nazis had to flee the country to escape Tito’s revenge. The writer, working in South Wales just after the Second World War, lived in a hutted encampment that also housed many of those (Yugoslavs and others) who had chosen the wrong anti- Nazi army to fight in, and as a result had lost their families and homelands, and were doomed to permanent exile, labouring in a foreign land.

Stalin was triumphant. The warm water ports on the Mediterranean that Russia had craved for 150 years seemed now firmly in his control. But the plans even of capitalist superpowers not infrequently go awry. The new Yugoslav ruling class were restive as clients of the Russian empire, and Tito aspired to be Yugoslav dictator in his own right, not merely as Stalin’s vice-regent. Relations between Stalin and Tito deteriorated, and then the Comintern, on Russian orders, expelled the Yugoslav party from the fold. When other countries became uneasy under the yoke later—on Hungary in 1956, Czechoslovakia in 1968—the preponderance of opinion within the native ruling class was in favour of Russia, against the home-grown boss. In Yugoslavia it was not so. Tito had done too good a job in gaining control of the party machinery and its propaganda weapons. Though border incidents were almost a daily occurrence for some years, Stalin was never able to re-assert his control.

Having carried out many purges in the cause of Stalinism, Tito now carried out others in the cause of anti-Stalinism. Opponents were executed or jailed. Twelve thousand Yugoslav Stalinists found themselves in prison on the Adriatic island of Goli Otok. At the same time the other Balkan states, under Russian instructions, rooted out and put on trial any members who the Russians felt might follow Tito’s example, and declare their independence of Stalin. Executions of so-called Titoists became common throughout the remaining Stalinist countries of eastern Europe.

But Tito himself survived, and after Stalin’s death his successor Khruschev visited Yugoslavia to explain that it had all been a mistake. Thereafter Tito played a cunning game, allowing both superpowers, Russia and America, to woo Yugoslavia with economic and military aid. He also tried to create a “third world” bloc under his own leadership, independent of both Russia and America. In all things, he defended and promoted Yugoslav capitalism.

He claimed that capitalism in Yugoslavia was socialism; a good propaganda line to persuade the oppressed and exploited that they are really free. Tito himself saw the facts clearly enough, when his own interests were not involved, and he himself described the Russian system as state-capitalism. But honesty in capitalist societies is often available for export only.

Tito’s dictatorship remained as tyrannical as he felt necessary for the prolongation of his own power and his state-capitalist system, and he continued until the end to put opponents in jail, such as his former comrade Djilas, or to have them killed. In 1971 he purged the Croatian party leadership for “nationalism”, and followed it with a purge of the Serbian party leadership for “liberalism”. Dissidents who fled abroad were pursued by the Yugoslav secret police. The Times (29.4.80) reluctantly referred to the accusations of Yugoslavia “arranging the murder of Croat emigres”, and thus drew an indignant letter from a reader with a Serbian surname (Pavlowitch) reminding the editor (6.5.80) that “the list of murdered Serbs is also most impressive: at least one in Paris, three in Brussels, two in Canada, two in the United States, one in Stockholm and one in West Germany, the last one Dusan Sedlar, on April 16 in Munich. Not to mention the known cases of kidnapping, one in Switzerland and one in Rumania”.

As political boss of an autocratic country Tito was not dissimilar to others of the same kind. (And over eighty per cent of the world’s population is in the grip of dictators: capitalism breeds them, as a dead rat breeds maggots.) While his opponents were fitted with prison garb, or their winding sheets, Tito sported flashy uniforms and diamond rings, and his hat always had more gold braid than anyone else’s. While those who differed from him were incarcerated in their cells, or their graves, Tito was driving expensive fast cars, or was out shooting game. While those who had not been spry enough to change sides at exactly the right moment stared through the barred windows, if they were that lucky, Tito amused himself in luxurious speed boats, cruising round his island of Brioni. While those who held incorrect opinions forced down prison food, or themselves fed the worms, this large-bellied bon vivant savoured the succulent delicacies of state banquets.

And the great majority of the Yugoslav people, drudging in workshops and factories, and on the farms and railways, accepted it all os being part of the natural order of things. Since they supported capitalism, they were brainwashed by Tito’s propaganda machine into hero-worship of “the leader”. Turning out in their thousands to Tito’s funeral ceremonies, they demonstrated their own political ignorance, just as so recently the loyal crowds in Iran turned out to support the Shah, or in Uganda to support Amin. In a socialist—a sane—society people will find it difficult to understand how such a blood-stained monster as Tito was ever allowed house-room by human beings—much less permitted to lord it over an entire country as a dictator.

Alwyn Edgar