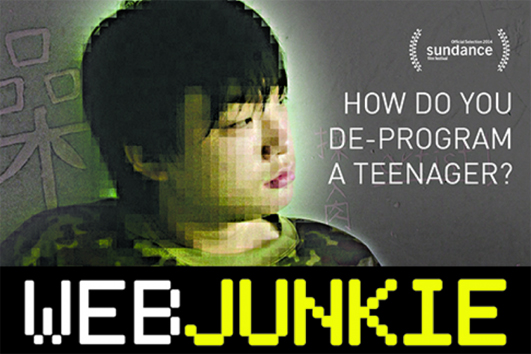

Propaganda: Electronic Heroin

Anyone switching on half way through Web Junkie (BBC4) might think they’ve tuned in to a grim dystopian drama, rather than a documentary. Uniformed teenagers march through a Chinese boot camp with drab walls and blandly functional furniture. Some have been tricked into joining, or have woken up there after being drugged. All have been sent because they have been diagnosed with ‘internet addiction’, which the state claims is ‘the number one public health threat to its teenage population’. More than 400 such boot camps have been built across China since ‘internet addiction’ was classified as a clinical disorder. Web Junkie: China’s Addicted Teens follows several teenagers and their parents through the treatment provided by the Daxing ‘Chinese Teenagers Mental Growth Centre’ in Beijing.

This treatment to encourage ‘mental growth’ is a bizarre combination of lectures, drill exercises, medication, ‘self-reflection’ in an isolation room, patriotic songs and group therapy. The latter are awkward conversations between the children, their parents and nurses, mostly about their distant relationships. In one of his lectures to a class of parents, the centre’s professor connects family problems with being too pushy for academic achievements. This is the only time in the film that raises wider explanations for ‘internet addiction’ (or ‘electronic heroin’, as it’s called). The faults in society which make some teenagers prefer a virtual life aren’t discussed. Nor is the possibility that ‘internet addiction’ is a social construct, although if the centre’s authorities realised this, they would be doing themselves out of a job. The existence of these centres reinforces the definition of an ‘internet addict’ and therefore fuels the issue.

The regime at the Daxing centre looks more like that of a prison than a hospital. Despite claims of a 70 percent success rate, its inmates are mostly disparaging of its programme and the notion that they have an illness. Even if prolonged internet use has affected their relationships or motivation, getting them to sing and do press ups probably isn’t the best way to address the problem. And even if they are ‘cured’ and can rejoin society as a productive unit, they’re likely to end up in a dull office job, still sat in front of a computer for eight hours a day.

MIKE FOSTER