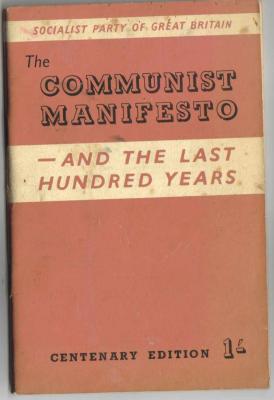

Preface (1948)

This year being the centenary of the publication of the Communist Manifesto we are reprinting the latter, together with Engels’s preface to the authorised English translation. Prefixed to these is an introduction we have prepared covering the working-class movement over the past hundred years. Limitations of space have compelled us to be brief; we have had to omit reference to working-class development in Canada, India, China, Japan, Australia, and elsewhere, as well as to make only fleeting references to many important phases of the movement; but we have endeavoured to give a clear and lucid picture of those developments that have had a deciding influence upon the main course of the working-class movement since 1848.

At the time the Manifesto was written the term “Socialism” was generally used to cover movements that favoured co-operative experiments of different kinds. To distinguish themselves from these utopians and their degenerate successors the group that produced the Manifesto adopted the name “Communist.” Thus references in the early part of the introduction to “Communists” and “Communist Parties” must not be taken to mean the people and parties that have masqueraded under similar names since the Russian Upheaval of 1917.

The Manifesto was the basis of the modern scientific socialist movement but since phrases from it have been used from it to support the aspirations of reformist movements we would draw the reader’s attention to a statement made by the authors in their joint preface to the 1872 edition:

“No special stress is laid on the revolutionary measures proposed at the end of Section II. That passage would, in many respects, be differently worded today.”

When the Manifesto was written the authors were young men filled with the passion of revolt against the oppressive conditions of their times, and looking to revolutionary uprisings as means to secure the abolition of privilege; the extensive studies of later years and the accumulation of practical political experience modified their views in many respects, and particularly in the decision they have indicated in the above quotation.

One other matter we would draw to the reader’s attention. A reference in the Manifesto to the introduction of certain measures after the workers have conquered political power is proceeded by the following two paragraphs:

“We have seen that the first step in the revolution by the working class is to raise the proletariat to the position of ruling class, to win the battle of democracy.

The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degrees, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments in the hands of the State, i.e. of the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total productive forces as rapidly as possible.”

Thus Marx and Engels did not support the position taken up by the reformists, that programmes of reforms should constitute the demands of social democracy from capitalist governments, but, on the contrary, they proposed that certain measures should be adopted to take industry out of the control of the capitalists after the workers had obtained control of political power. Even in this direction it is unthinkable that a section of the population, knowing it was doomed, would continue to play its part in industry, calmly awaiting the taking away of its privileges piecemeal.

This was one of the problems that forced Lenin and his associates to retreat. However, we are convinced that political and economic development since their day would have caused Marx and Engels to reconsider their attitude on the question. Neither of them stood still but faced the practical world scientifically, ruthlessly casting aside that which historical development had shown to be obsolete.

The Executive Committee of the Socialist Party of Great Britain.

February, 1948

The Last Hundred Years 1848 and the Background of the Times

Revolution and Counter Revolution

The International Working Men’s Association of 1864

Birth of Social Democratic Parties

The Erfurt Programme of 1891 and Reformism

Birth of the Socialist Party of Great Britain in 1904

The First World War and the Social Democratic Collapse

The War and the Socialist Position

The Influence of Bolshevism and the Growth of Italian and German Dictatorships

Labour Governments and the Shadow of War

The Second World War and the End of a Delusion

Labour Takes up the Capitalists’ Burden Supported by the Communists

The Last Hundred Years – 1848 and the Background of the Times

What changes have taken place in the world, and what a multitude of vain hopes have been buried, since a tiny group of refugees gathered in London a hundred years ago and flung a challenge to the privileged classes of its time in the form of the Communist Manifesto! The world they lived in was seething with revolt against a multitude of privileges, born out of the mixture of old social forms fighting to maintain their existence and the new ones that were undergoing a painful birth. Relics of Feudalism, conquered in England and France, still weighed heavily on budding modern industry everywhere; machine production had made great strides in England, the most advanced country, but the hand worker still monopolised a considerable part of the productive process. On the European continent production and distribution were mainly carried out by the peasant, the small trader and the small producer, while the financial groups based upon trading were struggling for political influence. Large manufacturing units were scarce and the working class was composed of a relatively small number of factory workers and a large number of employees of small producers and traders, the latter still entangled in relics of the old guild methods, both the good and the bad. This mixed class of workers was itself only a small fraction of the total population.

The revolutionary phrases of the time were largely the bitter cries of oppressed groups seeking elbowroom under despotic political systems not yet freed from feudal encumbrances. It was a time when the old order founded upon the cleavage between lord and serf, with customary payment and labour dues, had broken down or was in process of dissolving, and the new order based upon capitalist and worker with freedom of contract and wage labour, was trying to find its way. The peasant, still by far the most numerous and most depressed class, was overburdened with work and taxes, lacked education and cohesion, and hung on to his dwindling patches of land without any idea of getting a living outside of unprofitable agricultural labour; in the easterly regions of Europe the peasant lived under feudal arrangements that were little different from those of his forefathers. The small producer and the hand worker revolted against the new machine production which competed against his hand work, lowered the standard of living and threatened to, and often did, reduce him to starvation. The anger of the worker was directed partly against the developing group of large capitalist employers. The small producers and traders of all descriptions, like the peasant, hung on grimly to their small properties and sank down nearer to ruin as they were unable to compete successfully with large capitalist enterprises. They wailed against the competition of the new industry, were crushed by taxation and cramping legislation, vacillated between support of the advocates of democracy, sections of whom threatened to deprive them of their small properties, and support of the governments under which their small properties tended to disappear anyway.

Allied with most of the governments was a rich financial aristocracy, part of whom had made fortunes out of government difficulties and part out of the new industrial developments. Supreme power rested with the wealthy landowning aristocracy whose power was based either upon old feudal estates or upon landholding acquired through the break-up of feudal estates. This class was the wielder of political power and the state was fashioned in harmony with its interests. It was thus the supreme enemy and had at times allied against it loose and uneasy associations of other sections of the population. The mass of the population was without either a vote or any form of political control of government policy.

The maelstrom of conflicting social interests was reflected in conflicting social policies and the programmes based upon those policies. The French Revolution of 1789 had been a tremendous upheaval which had brought forth a variety of equalitarian ideas that provided food for thought for generations afterwards and had an immense influence on ideas and on the people who were searching for remedies for social grievances in the middle of the nineteenth century. The students at the continental universities, drawn mainly from classes outside the circle of ruling factions, were deeply affected by the prevailing disabilities, and their studies were influenced by the revolt against onerous conditions. Here and there groups of students discussed earlier historical periods in the light of the present; they were keenly interested in the controversies concerning the French Revolution and the philosophical and social ideas of the protagonists of that revolution. Thus the spokesmen of revolutionary ideas were generally students and professors at the universities who found much in common with the views of the more advanced coming from working-class surroundings.

Apart from the social forces already mentioned there was another disturbing influence, that of nationality. The distribution of people into national units was far different then from what it is now, and Europe was wrapped in struggles for self-determination that cut across the struggles between social classes although inspired by the economic development that threw up those struggles. The German-speaking countries were united in loose and warring confederations, with Prussia and Austria wrestling for mastery. Italy and Hungary were subject states dominated by Austria; Poland was split between Russia, Austria and Prussia, and stirred by the memory of former glory compared with present subjection. There were also numerous other groups struggling for independence from powerful neighbours. Patriotism, or self-determination, was therefore one of the vital moments that engaged the attention of budding revolutionists, particularly those that came from the universities.

The experience of the French Revolution weighed heavily upon the advocates of working-class interests who were active in the first half of the Nineteenth Century. To them a change in the basis of society could only be accomplished by force of arms, just as the street barricade was the general answer to the oppression. Those who supported the Communist Manifesto were deeply impregnated with this view, and it would be many years before even Marx was willing to allow that here and there the social revolution might be accomplished without an armed rising of the people. The development of the means of warfare rendered obsolete the barricade battle which depended on the efficiency of bodies of men equipped with small-arms. But the idea lived on in another form. So deeply was the violent idea engraved upon the minds of the advocates of working-class emancipation that the programmes of all the major Social Democratic Parties that were later established contained a demand for the abolition of the standing army and the substitution for it of a militia force, the “armed people.”

For a hundred years the working-class movement has vacillated between four different roads, each of which had guides that proclaimed it the road to freedom: The armed conquest of power by a small determined group which would hold on to power until the majority were converted – Blanquism; the seizure of the means of production and distribution by some form of industrial action – Syndicalism; the accomplishment of ever more sweeping reforms until Capitalism had been reformed out of existence and society had “glided” into Socialism – Reformism; and the conquest of power by a majority of class-conscious workers antagonistic to reform policies, spurning leadership, using democratic methods, and imbued with the single aim of abolishing the capitalist ownership of the means of production and distribution in order to replace it by common ownership – revolutionary political action to establish Socialism. A confusing note across all these roads has been the moan of the suffering small proprietor, ground down under the weight of modern industry; seeking working-class assistance to relieve him of his burdens he has failed to grasp the fact that he is a relic of earlier social development, doomed to stagger on, but whose real interest lies in the abolition of the very conditions that force him to struggle for a hard and precarious existence. This group often expresses its social outlook under the title of Anarchism, a name which has covered a multitude of sins.

In the painful history of the working class movement a variety of different parties have been formed; some following one or other of the above roads, but most of them striving to combine all the roads into one main road – and bringing only ruin in their wake. “Compromise” and “Unity” have been the magic symbols under which these combinations have masqueraded. Most of these parties have claimed the Communist Manifesto as their basis and guiding star, and have sought to give a foundation to this claim by quotations of sentences from it. Some of these claims can be removed forthwith by intelligent reference to the Manifesto itself.

Revolution and Counter Revolution

The small group that published the Communist Manifesto, as a statement of the working-class position and a challenge to the privileged classes of its time, had only a brief existence. Shortly after the appearance of the Manifesto the European world was in the throes of revolutionary outbreaks which, starting in France in February, soon engulfed all the European states in a turmoil that lasted through 1848 and 1849 and caused those that adhered to the Manifesto to disperse to the different centres of battle. It was the attempt of the capitalist class to conquer exclusive political dominion of the various states. Here and there the Communists intervened in an attempt to turn the struggle into a working-class movement for emancipation; but the Communists were too few and the workers too immature for these efforts to have any permanent effect on the course of the struggle. Although the workers were the most active element, and worst sufferers in these alleged liberating movements, all they reaped for their sacrifices was bitter persecution, massacres, and a firmer riveting of the bonds of wage slavery upon them. The incidents connected with the suppression of the Chartist movement in England, the Red Republican movement in France, and other movements in Austria, Germany, and Italy, are examples of the ferocity of the ruling classes when they believe their privileges are threatened.

When the smoke from the revolutionary struggles of the time had cleared away the progress of the capitalists towards political supremacy had moved with varying fortunes in different countries. In England the industrial capitalists had conquered political domination; in France capitalist timidity and vacillation, partly born out of fear of the working class, had enabled a political adventurer, Napoleon III, to stand on the backs of the peasantry and filch from the capitalists most of the fruits of victory; in Germany and Austria a compromise with land holding and financial aristocracy left the capitalists still politically subservient; and in Italy the movement sank in the morass of national subjection. The position changed little during the forties, fifties and sixties whilst industry itself was coming more and more under the sway of capital; machinery, the concentration of industry, and the development of the world market was accomplishing what the political struggle had failed to achieve, the undermining of the power of the landed aristocracies and the conversion of peasants and small proprietors into wage workers.

In the meantime groups that had subscribed to the Manifesto were broken up and there was a prolonged lull in working-class activity. The latter was partly due to discoveries of fresh gold fields in distant parts of the world to which many of the active and disappointed workers emigrated in the hope of finding the comfort and security denied to them at home. America, which was making great strides in industrial development, and whose vast tracts of unoccupied land beckoned to the disgruntled craftsmen and disillusioned revolutionist, also drew off large numbers of politically active workers. The joint authors of the Manifesto, Marx and Engels, realising the days of practical activity had momentarily passed, withdrew from a prominent part in the working-class movement for many years; the one to pursue his economic studies, and the other to enter a manufacturing business in order to secure his own subsistence and also to assist Marx do likewise. The studies of the latter bore fruit in 1859 with the publication of the “Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy,” the first draught of his exhaustive analysis of capitalist production, which was eventually incorporated into the first volume of “Capital,” published in 1867.

The preface to the “Critique” contained in concentrated form a statement of what constituted the Materialist Conception of History, the point of view from which Marx analysed industry and political and economic movements. His outline of this attitude has never been improved upon in depth and insight, sweep, and trenchancy, and it therefore merits quotation:

“In the social production which men carry on they enter into definite relations that are indispensable and independent of their will; these relations of production correspond to a definite stage of development of their material powers of production. The sum total of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society–the real foundation, on which rise legal and political superstructures and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production in material life determines the general character of the social, political and spiritual processes of life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but, on the contrary, their social existence determines their consciousness. At a certain stage of their development, the material forces of production in society come in conflict with the existing relations of production, or–what is but a legal expression for the same thing–with the property relations within which they had been at work before. From forms of development of the forces of production these relations turn into their fetters. Then comes the period of social revolution. With the change of the economic foundation the entire immense superstructure is more or less rapidly transformed. In considering such transformations the distinction should always be made between the material transformation of the economic conditions of production which can be determined with the precision of natural science, and the legal, political, religious, aesthetic or philosophic–in short ideological forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out. Just as our opinion of an individual is not based on what he thinks of himself, so can we not judge of such a period of transformation by its own consciousness; on the contrary, this consciousness must rather be explained from the contradictions of material life, from the existing conflict between the social forces of production and the relations of production. No social order ever disappears before all the productive forces, for which there is room in it, have been developed; and new higher relations of production never appear before the material conditions of their existence have matured in the womb of the old society. Therefore, mankind always takes up only such problems as it can solve; since, looking at the matter more closely, we will always find that the problem itself arises only when the material conditions necessary for its solution already exist or are at least in the process of formation. In broad outlines we can designate the Asiatic, the ancient, the feudal, and the modern bourgeois methods of production as so many epochs in the progress of the economic formation of society. The bourgeois relations of production are the last antagonistic form of the social process of production–antagonistic not in the sense of individual antagonism, but of one arising from conditions surrounding the life of individuals in society; at the same time the productive forces developing in the womb of bourgeois society create the material conditions for the solution of that antagonism. This social formation constitutes, therefore, the closing chapter of the prehistoric stage of human society.”

Marx had already given a brilliant example of the materialist conception of history to current events in his study of French history during 1848-1852, which was published under the title “The Eighteenth Brumaire.”

The International Working Men’s Association of 1864

At the beginning of the sixties the trade union movement in England began to wake up, and some prominent trade unionists formed the London Trades Council advocating the extension of the suffrage and political action for the purpose of influencing legislation in directions favourable to the workers; in France the laws against combinations of working men were somewhat eased with the object of inducing the workers to adopt a less antagonistic attitude to the regime of Napoleon III, and the visits of French workers to England were fostered in the hope that what they learnt there would contribute to French industrial efficiency; in Germany, Lassalle began the agitation that culminated in the formation of the “Universal German Working Men’s Association.” Lassalle conducted a violent agitation that made him one of the most spectacular figures in Germany and eventually brought him into touch with the German Imperial Chancellor, Bismarck. Lassalle’s agitation had a two-fold object: universal suffrage and state aided co-operative productive associations. The progress of the movement was too slow for the impatient and ambitious spirit of Lassalle and he thought he could hasten it by meeting Bismarck and selling industrial peace for universal suffrage and state aid to the co-operatives. The evidence that subsequently came to light suggests that he came near achieving his purpose. How far ambition also moved Lassalle will never be known but his opponents put the worst construction on his efforts. One thing is certain: it was Lassalle who was mainly responsible for the revival of the working-class movement in Germany, and after he died it was mainly organisations that grew out of his and the German Peoples’ Party that were eventually united to form the German Social Democratic Party.

At the beginning of the sixties there were meetings between English and French workers, mainly inspired by a desire to prevent the immigration of nationals into one country from another during strikes; these immigrations were arranged by the employers for the purpose of breaking strikes and lowering the standard of living. The International Exhibitions arranged by the governments at the time had enabled French and English workers to meet one another and confer; and so also had the international demonstrations that were held to protest against Russian brutality to the Poles which were attended by foreign refugees domiciled in London. At one of these international demonstrations, held in London in 1864, a resolution was passed in favour of the formation of an international working men’s association. Marx, who had been especially invited, emerged from his retirement to attend this meeting as he believed that at last the workers were really on the move again in a way that promised substantial results. A committee was formed to prepare the framework of the new organisation and Marx was appointed a member of it, drafting the Inaugural Address, the Rules and a preamble to them and, subsequently, writing most of the proclamations published by the International Working Men’s Association. The Preamble to the Rules was a brief and concise statement intended to define the basis of the new organisation. It consisted of the following paragraphs:

“Considering.

That the emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves, that the struggle for the emancipation of the working classes means not a struggle for class privileges and monopolies, but for equal rights and duties, and the abolition of all class rule;

That the economical subjection of the man of labour to the monopoliser of the means of labour — that is, the source of life — lies at the bottom of servitude in all its forms, of all social misery, mental degradation, and political dependence;

That the economical emancipation of the working classes is therefore the great end to which every political movement ought to be subordinate as a means;

That all efforts aiming at that great end hitherto failed from the want of solidarity between the manifold divisions of labour in each country, and from the absence of a fraternal bond of union between the working classes of different countries;

That the emancipation of labour is neither a local nor a national, but a social problem, embracing all countries in which modern society exists, and depending for its solution on the concurrence, practical and theoretical, of the most advanced countries;

That the present revival of the working classes in the most industrious countries of Europe, while it raises a new hope, gives solemn warning against a relapse into the old errors, and calls for the immediate combination of the still disconnected movements;”

According to the first rule that was adopted the Association aimed at “the protection, advancement and complete emancipation of the working classes.” Here was the thin edge of reform. The rules gave the Central Council considerable power and this was the cause of friction later on; a number of those serving on this council and acting as officers of the Association were old members of the Communist League. It is significant to notice that nowhere in the Address, the Preamble or the Rules is there any reference to common ownership of the means of production although there were constant references to the emancipation of labour. From the Communist Manifesto to the International Working Men’s Association was a long step in years, but it was partly a step backward; an attempt to get a large body together without placing a great deal of stress upon clarity of outlook. It was an attempt to unite workers on a programme that was broad enough to include those with a variety of fundamentally conflicting views in the hope that the discussions and the struggles of the organisation would eventually lead to the shedding of ideas that were anti-working and thus clear the outlook of the workers. It appears to us that Marx was unduly optimistic. The International lasted only eight years and the greater part of its time was taken up with largely fruitless and bitter internal strife between the anarchists, headed by Bakounin, and those who advocated political action, headed by Marx. In 1872 the struggle ended with the expulsion of the anarchists and the transference of the headquarters of the Association to New York. This was practically the end of the International; it was partly precipitated by the defeat of the Paris Commune, established at the end of the Franco-German war of 1871. Marx wielded the supreme influence in the International, but was not always in harmony with democratic procedure owing to his anxiety to get the workers to adopt an attitude which he believed was in line with their interests, the transference of the headquarters out of reach of anarchist influence was itself an admission that the workers were not yet ready to adopt a socialist position. The anarchists strove for a time to carry on an international of their own, claiming that it was the legitimate expression of the organisation founded in 1864, but the attempt petered out after a few years.

The Franco-German war raised a question that has since split the social democratic movement over and over again; the question of war. To those who claimed to base their views on Marxism it was a question of tactics; to those who did not it was largely a question of ethics and blind patriotism. To those who took their stand on the tactical position the attitude on a given war depended upon their estimate of the effect support of, or opposition to, the particular war would have upon the development of the Socialist movement. Lassalle and Marx had earlier had antagonistic views on the possible outbreak of war between France and Austria; Marx holding that the Napoleonic regime was a blighting influence on the progress that might spread over Europe, and, consequently, a victory for France would be a defeat for the progressive forces; Lassalle, on the contrary, held that the defeat of France would spell the triumph of Russia, who would interfere on the side of Austria, and the increase of the reactionary power of Russia over the destinies of Europe. When the Franco-Prussian war broke out the Social Democratic parties split on the attitude to adopt towards it; one section in Germany declared against the war whilst the other issued a proclamation supporting the German government as long as it waged only a defensive war against France. The International issued an address supporting the latter section and urged the social democrats to do all in their power to prevent the German government from turning the war of defence into a war of offence. Germany was declared to be on the defensive as long as she did not make any territorial demands upon France; if she made territorial demands then it would be declared that the war of defence had been turned into a war of offence – as if the latter were not bound to be the natural outcome if German arms were successful! The weakness of this attitude was subsequently made clear when it was revealed that although Napoleon had actually declared war Bismarck had deliberately manoeuvred him into position where he was compelled to do so. When account of it is taken the relatively small number of Social Democrats at the time it seems ridiculous to have expected them to have any influence on the direction the war would take, especially as every government plays upon popular ignorance by bringing forward arguments to show they are resisting the heinous designs of an aggressor nation.

The war went ill for France; Germany captured Napoleon, two huge French armies, and finally invested Paris. A provisional French government was formed, ostensibly to carry on the war but in reality to prepare capitulation terms. The only armed force of any consequence left to defend Paris was the National Guard, a voluntary force equipped out of funds provided by themselves. The Government tried to disarm the National Guard and steal its cannon; it was afterwards found that one of the peace conditions imposed by Germany was the disarmament of Paris. The attempt to steal the cannon was frustrated and provoked an rising, the real motive behind which was patriotism. The Government slipped out of Paris to Versailles and the committee of the National Guard took control of affairs and prepared to resist the siege, which was now ostensibly taken over openly by the Provisional Government. By decree of the Committee of the National Guard elections were held in Paris to form a properly constituted government, in place of the one that had fled and, behind the scenes, had capitulated to the enemy, and in March 1871 the democratically elected Paris Commune took over supreme control and the defence of Paris; a defence that was hopeless from the beginning in spite of the heroism of the Parisians. Germany released large numbers of captured French soldiers and put them at the disposal of the Provincial Government at Versailles, and the latter attacked the Communards with slander, treachery, and unbridled ferocity; the returned soldiers, smarting under their recent defeats, were willing tools in acts of unbelievable brutality. After three months of desperate fighting, at the end with valour of despair, the Commune was crushed and its partisans given up to indiscriminate slaughter; a slaughter that was carried on long after the fighting was over. Those who survived but failed to escape were transported in thousands, under horrible conditions, to spend years of misery in a penal settlement.

During the siege, under the pressure of the furious bombardment, some of the committees appointed by the Commune brought in measures to improve the conditions of the workers that the latter had been fighting years for in vain. It was related that order was so far established that people could go about their work with a freedom that had never been known in living memory; and that women could walk the streets at any hour of the day or night without risk of molestation. Cesspools of vice were cleaned up, thieving and burglary disappeared, and the necessities of life that were available, were evenly distributed. Unfortunately the differences of opinion and uncertainty that prevailed in the International were reflected in the Councils of the Commune and were a considerable influence in its early defeat.

The International issued three Manifestoes on the Franco-Prussian War, all of which were composed by Marx. The final manifesto “The Civil War in France,” was an analysis, a defence of the Communards, and a threat, concluding with the following words:

“Workingmen’s Paris, with its Commune, will be for ever celebrated as the glorious harbinger of a new society. Its martyrs are enshrined in the great heart of the working class. Its exterminators history has already nailed to that eternal pillory from which all the prayers of their priest will not avail to redeem them.”

The fury aroused in governmental breasts by the Paris Commune, and the chorus of calumny that was poured upon it, frightened away from the International influential English trade union leaders; the furious persecution by the French government broke up the French sections, many members of which were either killed, transported, or became fugitives, including working men of other nationalities who had rallied to its support. The International itself took over, as far as it could, the care of dependants and fugitives; the mutual recriminations of the latter did not help the dwindling influence of the International, adding to the internal discord that brought about its dissolution.

Birth of Social Democratic Parties

For a long time after the Commune the movement for working-class emancipation was unable to raise its head in France. Germany faired better and the movement there grew, in spite of the persecution of its protagonists, until the followers of Lassalle uniting with those who gave allegiance to Marxism formed the German Social Democratic Party at a Gotha Conference in 1875. the programme on which the two groups united was a mixture of reforms and false economic doctrines, which called forth a biting criticism from Marx that was afterwards published under the title of “The Gotha Programme.” Phrases from this criticism were later distorted by Lenin and his associates into justifications for the tortuous policy pursued by the Bolsheviks.

The German Social Democratic Party made such considerable progress, securing the election of members to the Reichstag, that it inspired the apprehension of Bismarck. In an effort to crush the party advantage was taken of two attempts to assassinate the German Emperor in 1878. On the plea that the incidents were an offspring of social democratic agitation the press was used to stir up a campaign of animosity and prepare the ground for action. In October, 1878, a special Bill was passed through the Reichstag outlawing the Social Democratic Party, the Bill to remain in force for three years, subject to extension. This Bill made it criminal to hold meetings or organise in any form, sequestered the funds of the organisation and prohibited all its periodicals. The following extracts are examples of the sweeping nature of the anti-nature laws:

“Societies which by Social Democratic, Socialistic, or Communist attempts, seek to overthrow the existing order of State or society, are forbidden.

This applies also to societies in which Social Democratic, Socialistic, or Communistic attempts directed to the overthrow of the existing order of the State or society appear in a manner dangerous to the public peace, and especially to the concord of the different classes of society.

What refers to societies holds equally good of combinations of every kind.”

In spite of intense persecution and the vigilance of the police the Social Democratic Party, after the first few months of panic, managed not only to exist but multiply at an ever increasing rate. The general feeling of resentment against the severity of laws rallied thousands to their support who might otherwise have remained indifferent to their propaganda. They developed the art of subterfuge to a high degree, pitting their wits successfully against the government; periodicals were printed in Switzerland and smuggled into Germany under the noses of police officials; party members in the Reichstag, who were immune from the provisions of the Bill as long as they did not take action outside their functions, were able to give considerable aid in various ways. But this concentration upon immediate difficulties was obtained at the expense of theoretical clarity; much of the support they received was from those who had not grasped the implications of Socialism but wholeheartedly backed political and economic reforms, thus expanding the party on a false basis. At the 1890 election the Social Democratic Party polled a million and a half votes, becoming the strongest single party in Germany. This result convinced the Government of the futility of attempting to kill the movement and the anti-Socialist laws came to an end. By that time the party had become the strongest of its kinds in the world and served as a model to the similar organisations that were being built up in France, England, Belgium, Holland, Austria, and the United States. In England the Social Democratic Federation and the Fabian Society came into existence in 1883; the former claiming adherence to Marxism and revolutionary political action in theory if not practice, and the latter opposed to Marxism and propagating the idea of permeating society with a leaven of reform ideas that would, it claimed, transform society. What has emerged from this agitation is State Capitalism. Later both these parties had a hand in the formation of a definitely reform organisation, the Independent Labour Party, which was to a considerable extent the product of the trade union organisation of the unskilled workers and the desire for a labour organisation to take the political field independent of the Conservative and Liberal parties. In France returned refugees from the Commune commenced agitation, tried to capture a trade union movement that was beginning to lift its head, and formed political parties claiming to be Socialist. One of these parties, under the leadership of Guesde and Lafargue, adopted the theoretical basis of Marxism but also added the reformist programme that was, and still is stultifying the efforts of even the most advanced Social Democratic parties.

In the United States European immigrants had taken to America with them the theories, both sound and unsound, that flourished in the European movement. For a time the anarchists monopolised a good deal of the field until someone threw a bomb amongst the police during a demonstration on behalf of the eight-hour day at the Haymarket, Chicago, in 1886; the police, who had prohibited this entirely peaceful gathering, were in process of dispersing it with quite uncalled-for violence. The effect of the uproar roused by this incident, and the press campaign that followed, was largely responsible for the decline of the anarchist influence in the labour movement, after which a native American movement was set on foot by the growth of the Socialist Labour Party; out of this party the Socialist Party of America and other smaller organisations developed, all of them afflicted with the reformist virus.

When the Social Democratic parties were in process of growth another movement cut across them and retarded their development. This was the Syndicalist movement, backed by the anarchists and feeding upon disillusion; Parliamentary action had not brought any fundamental difference in the lot of the worker, in spite of the showy promises, and Parliamentary leaders were deserting to the enemy. The Syndicalists claimed that their method would by-pass political apostasy and they vigorously pressed their claim that the General Strike was a short and sharp road to social salvation for the workers. Industry was to be brought to a standstill by the workers not only refusing to work but also engaging in the wholesale sabotage of machinery and transport facilities; workers who were unwilling to participate in the movement were intimidated into doing so; anti-military propaganda was to weaken the power of the army; and finally the owners of the means of production were to be starved into submission. For a time the movement gained considerable support, even from leaders of the Social Democratic movement, but eventually the bitter experiences in strikes on a large scale forced most of the workers to realise that it was they who would be starved into submission long before the capitalists experienced the pinch of hunger. A general strike for a drastic object is foredoomed, but a general strike for some minor object might have a chance of success if the cost to the capitalist of conceding the object were less than the cost of a widespread stoppage of work. On the other hand to allow even such a movement to be successful is inviting its extension and might therefore, from the capitalist point of view, constitute a threat to the existence of the privileged order and hence to be resisted with the utmost power on this ground alone, as happened in England in 1926. It may be added that if we were to allow the possibility of the incredible happening and the workers were prepared to stop all work for the purpose of bringing about a social transformation then they could accomplish their purpose without taking this futile action by using their voting power with understanding. It is the workers’ political ignorance that keeps them where they are and not the failure of political action. The Syndicalist outlook was strongly represented at the early congresses of the Second International formed in 1889 and, although the definitely anarchist groups were expelled from it in 1896, the anarchists, as delegates of trade union bodies, continued to seriously disturb its deliberations.

The Erfurt Programme of 1891 and Reformism

In 1891 the German Social Democratic Party adopted a new programme at its conference in Erfurt; this programme was subsequently known as the Erfurt Programme, and, as it formed the basis and defined the policy of all social democratic parties throughout the world from that time onward, we are quoting it in full:

“The economic development of the bourgeois society leads by a necessity of nature to the downfall of the small production, the basis of which is the private property of the workman in his means of production. It separates the workman from the means of his production, and transforms him into a proletarian without property, whilst the means of production become the monopoly of a comparatively small number of capitalists and great landowners.

This monopolising of the means of production is accompanied by the supplanting of the scattered small production through the colossal great production, by the development of the tool into the machine, and by gigantic increase of the productivity of human labour. But all the advantages of this transformation are monopolised by the capitalists and great landowners. For the proletariat and the sinking intermediate grades – small tradesmen and peasant proprietors – it means increasing insecurity of their existence, increase of misery, of oppression, of servitude, degradation, and exploitation.

Ever greater grows the number of the proletarians, ever larger the army of superfluous workmen, ever wider the chasm between exploiters and exploited, ever bitterer the class struggle between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, which divides modern society into two hostile camps, and is the common characteristic of all industrial lands.

The gulf between rich and poor is further widened through the crises which naturally arise out of the capitalistic method of production, which always become more sweeping and destructive, which render the general insecurity the normal condition of society, and prove that the productive forces have outgrown the existing society, that private property in the means of production is incompatible with their rational application and full development.

Private property in the instruments of production, which in former times was the means of assuring to the producer the property in his own product, has now become the means of expropriating peasant proprietors, hand-workers and small dealers, and of placing the non-workers, capitalists and great landowners in the possession of the product of the workmen. Only the conversion of the capitalistic private property in the means of production – land, mines, raw material, tools, machines, means of communication – into social property, and the transformation of the production of wares into socialistic production, carried on for and through society, can bring it about that the great production and the continually increasing productivity of social labour may become for the hitherto exploited classes, instead of a source of misery and oppression, a source of the highest welfare and of all-sided harmonious development.

This social transformation means the emancipation, not merely of the proletariat, but of the entire human race which suffers under the present conditions. But it can only be the work of the labouring class, because all other classes, in spite of their mutually conflicting interests, stand on the ground of private property in the means of production, and have as their common aim the maintenance of the bases of the existing society.

The struggle of the working class against capitalistic exploitation is of necessity a political struggle. The working class cannot conduct its economic struggle and cannot develop its economic organisation, without political rights. It cannot effect the change of the means of production into the possession of the collective society without coming into possession of political power.

To shape this struggle of the working class into a conscious and united one, and to point out to its inevitable goal, this is the task of the Social Democratic Party.

In all lands where the capitalistic method of production prevails, the interests of the working classes are alike. With the extension of the world commerce and of the production for the world market, the condition of the workmen of every single land always grows more dependent on the condition of the workmen in other lands. The emancipation of the working class is therefore a task in which the workers of all civilised countries are equally interested. Recognising this the Social Democratic party of Germany feels and declares itself at one with the class-conscious workers of all other countries.

The Social Democratic party of Germany therefore contends, not for new class privileges and exclusive rights, but for the abolition of class rule and of classes themselves, and for equal rights and equal duties of all without distinction of sex and descent. Proceeding from these views it struggles in the present society, not only against exploitation and oppression of the wage-workers, but against every kind of exploitation and oppression, whether directed against class, party, sex, or race.

Proceeding from these principles the Social Democratic party of Germany now demands –

- Universal, equal, and direct suffrage, with vote by ballot, for all men and women of the Empire over twenty years of age. Proportional electoral system; and, till the introduction of this, legal redistribution of seats after every census. Biennial legislative periods. Elections to take place on a legal day of rest. Payment of representatives. Abolition of all limitation of political rights, except in the case of disenfranchisement.

- Direct legislation through the people, by means of the right of initiative and referendum. Self-government of the people in Empire, State, Province, and Commune. Officials to be elected by the people; responsibility of officials. Yearly granting of taxes.

- Training in universal military duty. A people’s army in place of the standing armies. Decision on peace and war by the representatives of the people. Settlement of all international differences by arbitration.

- Abolition of all laws which restrict or suppress the free expression of opinion and the right of union and meeting.

- Abolition of all laws, which, in public or private matters, place women at a disadvantage as compared with men.

- Religion declared to be a private matter. No public funds to be applied to ecclesiastical and religious purposes. Ecclesiastical and religious bodies are to be regarded as private associations which manage their own affairs in a perfectly independent manner.

- Secularisation of the school. Obligatory attendance at the public people’s schools. Education, the appliances of learning, and maintenance free in the public people’s school, as also in the higher educational institutions for those scholars, both male and female, who, by reason of their talents, are thought to be suited for further instruction.

- Administration of justice and legal advice to be free. Justice to be administered by judges chosen by the people. Appeal in criminal cases. Compensation for those who are innocently accused, imprisoned, and condemned. Abolition of capital punishment.

- Medical treatment, including midwifery and the means of healing, to be free. Free burial.

- Progressive income and property taxes to meet all public expenditure, so far as these are to be covered by taxation. Duty of making one’s own return of income and property. Succession duty to be graduated according to amount and relationship. Abolition of all indirect taxes, customs, and other financial measures which sacrifice the collective interests of a privileged minority.

For the protection of the working class the Social Democratic party of Germany demands –

1. An effective national and international protective legislation for workmen on the following bases:

(a) Fixing of a normal working day of not more than eight hours.

(b) Prohibition of money-making labour of children under fourteen years.

(c) Prohibition of night work, except for those branches of industry which from their nature, owing to technical reasons or reasons of public welfare, require night work.

(d) An unbroken period of rest of at least thirty-six hours in every week for every worker.

(e) Prohibition of the truck system.

2. Supervision of all industrial establishments, investigation and regulation of the conditions of labour in town and country by an imperial labour department, district labour offices, and labour chambers. A thorough system of industrial hygiene.

3. Agricultural labourers and servants to be placed on the same footing as industrial workers; abolition of servants’ regulations.

4. The right of combination to be placed on a sure footing.

5. Undertaking of the entire working men’s’ insurance by the Empire, with effective co-operation of the workmen in its administration.”

An examination of this programme will reveal the disappearance of all pretence to revolutionary action and an understanding of why the Social Democratic Party lost their way in the bog of reform. After analysing correctly the trend of existing society, asserting that the social transformation can only be the work of the labouring class, that the emancipation of the workers will mean the abolition of class rule and classes themselves, and that this can only be achieved by the workers conquering the political power, this analysis concludes with the statement that the Social Democratic Party “struggles in the present society, not only against exploitation and oppression of the wage-workers, but against every kind of exploitation and oppression, whether directed against class, party, sex, or race.” This lines the party up with every group that is out for some tin pot reform; sopping up the water in an overflowing bath instead of turning off the tap. Hence among the reforms that follow are a number that could not be of any interest to the workers and are obviously aimed at enlisting the support of the peasant and small proprietor. Those that come under the significant heading “For the protection of the working class” are mainly the kind of things the worker fights for by trade union action, so that the Social Democratic Party was taking to itself the functions of a trade union as well as those of a political party! Finally the carrying of all the reforms, which would require the effort of decades, would leave the workers still at the mercy of the capitalists, suffering poverty and insecurity whilst providing security and comfort for a privileged and idle class. If the party had concentrated single-mindedly upon the achievement of Socialism, with perhaps the demand for suffrage, instead of wasting most of the energies upon the fight for reforms – which increased in number as time passed – how different might have been the shape of things in Germany today, as well as the rest of the world!

The periodical crises that occurred during the nineteenth century, caused by the growing productiveness of industry and the more effective exploitation of the workers, brought about periods of intense working class dissatisfaction, which were generally mistaken for revolutionary fervour. At such times the workers were prepared to follow almost any group that promised the immediate relief of the misery that afflicted them. It was this uninformed discontent that swelled radical parties, giving a false impression of progress, and then, when the period of acute misery temporarily passed, depleted them again. Even Marx was so far influenced by the resentment provoked by crisis conditions as to place undue reliance upon them for building up of revolutionary feeling. The upsurge produced during and immediately after a war, by scarcity and onerous regulations, particularly in the defeated country, was placed in the same category. A hundred years of these conditions has helped towards dissipating the illusion, except amongst the shallow optimists who reach after short cuts to social salvation.

Birth of the Socialist Party of Great Britain in 1904

The twentieth century saw the beginning of the era of Labourism during which reform, as an end in itself, came into its own in working-class politics; representatives of labour entered capitalist governments, and here and there Labour governments were formed. This era also saw the beginning of genuine working-class revolutionary political parties which framed uniform principles that anchored them exclusively to the socialist objective, and policies that had the single-minded purpose of abolishing the capitalist ownership of the means of production and replacing it by common ownership. While the old Social Democratic parties envisaged a new society in which, according to their leading spokesmen, unequal privileges would still persist, the new parties set out to establish a new society based on the principle “From each according to his capacities; to each according to his needs.”

In England the various radical parties united to form the Labour Representation Committee in 1900 for the purpose of supporting the candidature of allegedly independent labour candidates for Parliament as well as others who claimed to adopt a progressive outlook; in 1906 this committee was converted into the Labour Party, and representatives were elected to Parliament on reform programmes, making apparent that its main function was to help the wheels of capitalism run smoothly. The Social Democratic Federation, while violently attacking its contemporaries for their reformist policies, at the same time supported similar reforms, strove for unity with them, and also engaged in political action by arrangements alternately with the Liberal and Conservative Party. Inside this party a group, which had spent years actively engaging in an attempt to convert it into a really revolutionary organisation, at last had to give up the attempt in despair and leave the organisation to form something that would really accomplish the end its members aimed at. In 1904 a new era in working-class politics commenced with the formation of the Socialist Party of Great Britain.

The object and declaration of principles that were laid down by the founders of this party will be found printed on the inside cover of this pamphlet, and they have remained to this day a clear and concise statement of the basis of the organisation, admitting of neither equivocation nor political compromises with the enemy for any purpose however alluring. Here is no flirting with reforms nor false and soothing catchwords to enlist the sympathies and support of those who lack political knowledge but, instead, a straightforward statement of the essentials of the working-class position under capitalism and the only road to its solution – the capture of political power by a working-class the majority of whose members understand what Socialism means and want it.

Immediately after its formation the party sent delegates to the International Socialist and Trade Union Congress that was being held in Amsterdam in 1904, but the delegates found that the international was composed of delegations with a variety of non-socialist views, and that the emphasis of the congress was upon futile reform measures; they further found that, in spite of their protests, their position at the Congress was reduced to that of passive allies of the English reform parties in discussion and action. The report the delegates brought back decided the party to withdraw from the International until the basis of delegation to the latter was such that only genuine socialist parties would be permitted. From 1904 until 1914 the Socialist Party, in complete independence and isolation carried on the work it had set its hand to of advancing Socialism as the only remedy for the manifold evils that afflicted the workers; pointing out that war was the inevitable outcome in a system of production that set national groups against each other in the pursuit of markets for the disposal of goods, the pursuit of sources of raw materials, and the control of trade routes to markets and sources of supply; that in the following out of these aspirations national groups were weighed down by the ever growing weight of armaments that each was compelled to maintain.

While the Socialist Party concentrated upon the dissemination of Socialist principles the Social Democratic parties associated with the International wasted their time in futile anti-militarist propaganda, alliances with capitalist parties on reform programmes, diplomatic compromises, and even toyed with the idea of persuading workers who neither understood nor wanted Socialism, to participate in a general strike against war. But the increasing efficiency of production and the quest for means to realise profit eventually drive the capitalist powers in the holocaust of war.

The outbreak of war in 1914 exposed to the world the weakness of the Social Democratic parties, whose alleged Socialist aspirations were lost in the discussions, on each belligerent side, as to whether the war was offensive or defensive. All over the world the Social Democratic and Labour parties gave their support to one or other side in a war which presented the spectacle of claimants to a socialistic outlook slaughtering each other in an exclusively Capitalist quarrel In Germany, France and England those who had been regarded as outstanding representatives of social democracy, and had even issued proclamations outlawing war, joined Capitalist governments to better ensure the victory of their respective national groups. Here and there were workers who, however uninformed they may have been in their conception of Socialism, yet were sufficiently conscious that the war was not waged in the interests of the workers. The effect on them of the social democratic debacle, and persecution by their erstwhile “comrades,” was to drive many of them to despair and apathy.

The First World War and the Social Democratic Collapse

Long before the outbreak of the war Social Democratic leaders, in spite of resolutions carried by the International declaring that all modern wars were capitalist wars, had given evidence of their shakiness on the question. A questionnaire on the subject was addressed to them by “La Vie Socialiste” in 1905 and the replies disclosed some curious ideas, including the justification of the conquest of backward groups in the interests of progress; Bebel, Bernstein, Vaillant, Ferri, and others supported “defensive” wars; Lafargue and Plechanoff did not make their attitude clear but appeared to be opposed to any sort of war; Kautsky was non-committal but could be read as supporting a “defensive” war; Hervé was the one outstanding exception who was whole-heartedly opposed to the support of any war on the ground that the workers had nothing to gain or lose in victory or defeat, yet Hervé revised his views in 1914 and urged the workers to join up the and fight for an allied victory!

While the professed Socialist parties of Europe were falling to pieces and revealing the frailty of their claims to represent the real interests of the workers there was one party that took its stand on the principles of Socialism, and on that ground declared its opposition to the war as a purely Capitalist conflict. This party was the Socialist Party of Great Britain. Immediately the war broke out its Executive Committee passed a resolution declaring that anyone who supported the war was unfit for membership of a Socialist party; in the September issue of the Socialist Standard the party published the following Manifesto on the War:

The War and the Socialist Position

WHEREAS the capitalists of Europe have quarrelled over the question of the control of trade routes and the world’s markets, and are endeavouring to exploit the political ignorance and blind passions of the working class of their respective countries in order to induce the said workers to take up arms in what is solely their masters’ quarrel, and

WHEREAS further, the pseudo-Socialists and labour ‘leaders’ of this country, in common with their fellows on the Continent, have again betrayed the working class position, either through their ignorance of it, their cowardice, or worse, and are assisting the master class in utilising this thieves’ quarrel to confuse the minds of the workers and turn their attention from the Class Struggle

THE SOCIALIST PARTY of Great Britain seizes the opportunity of re- affirming the Socialist position, which is as follows:-

That Society as at present constituted is based upon the ownership of the means of living by the capitalist or master class, and the consequent enslavement of the working class, by whose labour alone wealth is produced.

That in Society, therefore, there is an antagonism of interests, manifesting itself as a CLASS WAR, between those who possess but do not produce and those who produce but do not possess.

That the machinery of government, including the armed forces of the nation, exists only to conserve the monopoly by the capitalist class of the wealth taken from the workers.

These armed forces, therefore, will only be set in motion to further the interests of the class who control them – the master class – and as the workers’ interests are not bound up in the struggle for markets wherein their masters may dispose of the wealth they have stolen from them (the workers), but in the struggle to end the system under which they are robbed, they are not concerned with the present European struggle, which is already known as the ‘BUSINESS’ war, for it is their masters’ interests which are involved, and not their own.

THE SOCIALIST PARTY of Great Britain pledges itself to keep the issue clear by expounding the CLASS STRUGGLE, and whilst placing on record its abhorrence of this latest manifestation of the callous, sordid, and mercenary nature of the international capitalist class, and declaring that no interests are at stake justifying the shedding of a single drop of working class blood, enters its emphatic protest against the brutal and bloody butchery of our brothers of this and other lands who are being used as food for cannon abroad while suffering and starvation are the lot of their fellows at home.

Having no quarrel with the working class of any country, we extend to our fellow workers of all lands the expression of our good will and Socialist fraternity, and pledge ourselves to work for the overthrow of capitalism and the triumph of Socialism.

THE WORLD FOR THE WORKERS!

August 25th, 1914,

THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE.

The Party kept its promise and its attitude to the war was maintained from the beginning to the end, in spite of persecution and the numerous difficulties the membership experienced in carrying out its pledge under war conditions; their Socialist principles served them as an effective sheet anchor in a world transported to the realms of jingoism by the storms of war.

In 1917 the Bolsheviks captured power in Russia and a new movement developed that darkened the workers’ vision, set back the revolutionary clock, and brought forth a welter of publications that side-stepped the struggle for Socialism by concentrating upon the respective merits or demerits of Dictatorship and Democracy, much in the way that the Syndicalist movement had turned up a blind alley two decades earlier.

The working class was only a small fraction of the Russian population, the overwhelming mass consisted of peasants. The Russian autocracy ruled Russia in an autocratic and semi-feudal fashion, denying the people elementary democratic forms; secret organisations with different outlooks flourished, some of which adopted the anarchist method of the propaganda by deed, including political assassination; the peasants were weighed down by poverty and maddening regulations; capitalist development was hindered and professional groups subjected to strict surveillance and the denial of free expression. Russia, with a poorly equipped army that had to be kept in the firing line largely by the pistols of its officers, was bribed to take the part on the side of allies though the ruling clique was divided on the subject.

After numerous defeats and the spread of defeatist propaganda, dissatisfaction and despair was the cause of wholesale desertions. The court party lost influence and a provisional government of Liberals was constituted to carry on the war. The Bolshevik Party in alliance with the Left Social Revolutionary Party (the peasant party) seized the opportunity to come out with a programme of Peace, Bread, and Land. This propaganda was appealing and rapidly gained adherents. Soviets of workmen, soldiers and peasants had been formed in the latter days of the war and at first supported the Provisional Government against the Bolsheviks, but the Bolsheviks were eventually successful in gaining the controlling power in them.

By then the soviets had become a power alongside of the Duma (Parliament), with a far more popular basis, which the latter found it convenient to use on occasions. When the Provisional Government, on the abdication of the Czar, first took power in March 1917 the Bolsheviks were demanding the calling of a Constituent Assembly elected upon a democratic basis to decide the future constitution of Russia; later they were popularising the slogan “All power to the Soviets,” although they were still in a minority in them. By September the Bolsheviks had become possessed of supreme power in the Soviets, and in October the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party declared in favour of armed insurrection. In November the All-Russian Soviet Congress passed resolutions, moved by Lenin, in favour of the setting up of a temporary workers and peasants government pending the summoning of a Constituent Assembly. The Bolsheviks rapidly consolidated their position, which was based on the support of the majority of the Soviets. When the democratically elected Constituent Assembly, which the Bolsheviks had all along been demanding, finally met in January 1918 the Bolsheviks used their newly acquired power to dissolve it as they found the majority of the Russian people voted against them.

The plea put forward for the dissolution of the Assembly was that between the date of the elections and the sitting of the assembly the attitude of the people had changed and the Soviets represented their outlook more closely; the change must have been astonishingly rapid! As soon as the Bolsheviks felt secure in the saddle they set about implementing their pledges; peace negotiations were set on foot with Germany and Russia withdrew from the war to get on with the internal struggle. This struggle was supposed to bring about the establishment of Socialism in Russia within a few short years, but the optimists had left the backwardness of industry and the people out of their reckoning. Then commenced the attempt to twist the Russian movement into the expression of the quintessence of Marxism, and the Soviet organisation as the form at last discovered under which the workers could work out their emancipation, a claim that is now in the museum of history along with the dictatorship of the working class. One fatal miscalculation was made by the Bolshevik leaders, a miscalculation that revealed how out of touch they were with the working-class political progress in Europe; they relied upon a revolutionary storm overtaking Europe and compelling European Governments to leave them alone to work out their plans for a social transformation in Russia. The vicious peace treaty that the German Government were able to enforce at Brest-Litovsk was the first blow to their hopes. Like so may exiles before them the Bolshevik leaders had largely lived in a world of their own, with their eyes fixed upon Russia and their thoughts guided by what was happening in that economically backward country.

In the turmoil following the war, with the turn over from war to peace conditions, the Soviet idea (workers and peasants councils) spread widely along with the false conviction that at least one country was establishing Socialism and it behoved workers everywhere, particularly in the defeated countries, to rally round the prophets of impending revolution. In Germany a split occurred in the Social Democratic party; one section, the “Majority Socialists,” getting control of power through the strife that forced the German Emperor to abdicate; they proceeded to rule upon the lines of an orthodox Labour party with the grudging support of another section, the “Independents.” A third section, the “Sparticists,” sniffing the fumes from Russia, demanded a more drastic reorganisation of German society; but they were only a small minority. The sections came to blows when the minority emerged upon the streets and tried to impose their views by force of arms in a hopeless fight. With the assistance of the army officers of the old regime, who brutally murdered Karl Liebneckt and Rosa Luxemburg, the “Majority Socialists” crushed the “Sparticist” rising, and, owing to the means they adopted, sealed their own fate and prepared the ground for the growth of the Nazi party whose leading members were studying the methods adopted by the Bolsheviks in Russia. In other parts of Europe there were also brief risings after the Russian model.

For a first few years after the First World War Russian development and the declarations of policy of the Bolsheviks formed the principal items of discussion in “advanced” working-class circles all over the world, and many were the sheep that were led over the precipice. The controversies between supporters of Bolshevism and supporters of the old social democratic parties would fill volumes. Both the supporters of Bolshevism and its critics, apart from the lonely voice of the Socialist Party of Great Britain, took for granted that the Russian upheaval was a Socialist revolution. Some of the critics argued that although the Bolsheviks were adopting the correct methods of bringing about the revolution in Russia, their methods were not suitable for the advanced capitalist countries in Europe and America where democratic constitutions prevailed. The Bolsheviks retorted with the claim that the democratic constitutions in question were capitalist institutions incapable of being used by the workers in their struggle for emancipation; they therefore urged the working-class organisations to abandon the Parliamentary struggle and concentrate, like the Russians, on strongly centralised organisations with “enlightened” leaders who should be endowed with complete power and authority to secure the dictatorship of the workers – then the slogan started “Watch the Leaders”! The dictatorship in Russia was subsequently revealed to be not the dictatorship of the workers, nor even the dictatorship of the Bolshevik party, but the dictatorship of a small clique within the Russian Communist Party that had engineered itself into power and that later split into a contest between leaders after the death of Lenin.

The Influence of Bolshevism and the Growth of Italian and German Dictatorships

When news of the October 1917 upheaval in Russia and its consequences has accumulated sufficiently to enable some estimate of its significance to be gathered the Socialist attitude towards it was set forth in an article in the “Socialist Standard” in August 1918. In this article it was pointed out that owing to the backward nature of the economic conditions in Russia, and a lack of a class conscious working class, a Socialist revolution was out of the question in that country at the time, therefore that whatever the Bolsheviks were building up, it was certainly not Socialism. As further evidence of the accomplishments of the Bolsheviks accumulated, and the shape of things in Russia was revealed more clearly, the soundness of this attitude was demonstrated, and the party exerted all its powers of speech and literature to fight the evil influence that Bolshevism was exerting on the working-class movement in the West. The worst features of this influence were the glorification of leadership, the claim that Russian State Capitalism was Socialism, and the claim that the time for theory had passed and the time for action, blind action, had come. It was a period of ill-timed revolts, abortive unemployed marches, futile attempts to organise pettifogging soviets, the propaganda of slogans in place of knowledge, and the strutting of impotent and empty-headed leaders who clothed themselves with a little temporary limelight. All this helped to impede the budding understanding of Socialism and, along with disappointment at the failure of ephemeral programmes to get them anywhere, drove masses of workers to despair and to indifference to the genuine Socialist message. In Italy workers, fortified with empty Bolshevik slogans, seized the factories in some industrial areas and provided the excuse for the Fascist march on Rome, clearing the ground for the Fascist Dictatorship.

In Germany attacks on Parliamentary action and the glorification of naked force as the final arbiter helped to place the Nazi regime in power. In both countries a system of State Capitalism was built up somewhat after the Russian fashion. It is also significant that the leaders in both countries had been connected with the Social Democratic movement. The supporters of Bolshevism, in their haste for short cuts and their thirst for power, destroyed all resistance to dictatorship and brought themselves down in blind imitation of Russian methods. In Germany a Communist party that boasted millions of adherents faded away under the pressure of the Nazis, who borrowed their slogans to fight the impotence of the Social Democrats and to fortify their hold upon supreme power. The brutality of the Bolshevik leaders against internal and external opposition was matched in both Italy and Germany, and so likewise was the purging by the victorious cliques.

The Italian and German regimes ruthlessly followed the principles of capitalist progress, which had been summed up in the phrase “Expand or Bust”. Italy expanded by trying to build an empire for its depressed population in North and East Africa in the orthodox style of conquest, whilst Germany expanded by using the jackboot to trample down opposition in central European states. The Nazis added to their laurels by the fiendish cruelty of their anti-Jewish campaign, using the Jews as convenient victims to account for the depressed state of sections of the German population such as small proprietors and professional groups.

The British Empire, in older days the first imperialist power to get off the mark, had been challenged by Imperial Germany and thought that they had settled accounts with their rivals in the first world war but economic necessity had forced them to assist their rivals to their feet again, and the latter had cunningly exploited the situation. At the same time America had undergone a hothouse development and, although eventually drawn into the world war, had suffered least economically, finishing a creditor power with economic domination almost within its grasp. America commenced to forsake its self-sufficing policy and look more determinedly to Europe and the East for sources of raw materials to supplement its own vast resources, and for markets to dispose of the products it was producing with such abundance.