The economics of coal

When the coal mines were nationalised in 1947 a notice was stuck up outside the 1000 or so pits proclaiming “This colliery is now managed by the National Coal Board on behalf of the people”. This was widely interpreted, especially by many miners and their union leaders (some of whom took up top management posts in the NCB), to mean that from then on the mines would be run as a public service producing coal for industry and people on a non-profit-making basis.

Those who believed this had not read the small print in the Coal Nationalisation Act of 1946. For a start, this Act authorised the government to buy the coal mines from their owners; so the old owners were not expropriated for the benefit of the people but were bought out by the government, being paid the full value of their assets in the form of interest-bearing government bonds. Secondly, the Act established the NCB as a commercial enterprise with a statutory obligation, like all other nationalised industries, to arrange its finances in such a way that, taking one year with another, its income should be sufficient to at least meet what a 1961 government White Paper on The Financial and Economic Obligations of the Nationalised Industries described as “all items properly chargeable to revenue”, defined as ‘”interest, depreciation, the redemption of capital and the provision of reserves” as well as operating costs.

There was no question, then, of the NCB producing cost-price coal to meet needs, as some naive Labour Party supporters imagined. On the contrary, it was charged with making sufficient profits to pay interest not only on capital advanced by the government for investment in coal production but also on the compensation bonds that the former owners had received. The NCB was in fact also required to make sufficient profits to pay the full value of these bonds (“redemption of capital”), which amounted to some £388 million at 1956 values. So, whatever else can be said about the nationalisation of the coal industry, it can’t be said that it was against the interests of the former mine- owners. They received a generous “compensation”, which of course they immediately re-invested with a view to profit in some other line of productive activity.

By law, then, the NCB was obliged to try to make sufficient profits not only to cover costs but also to pay its debts to the government and the former owners. This is still the case today, though for various reasons the NCB has not always been able to meet its statutory obligation here.

The main reason for this was the production of cheap oil that began in the late 1950s and flourished during the 1960s. Oil and coal are in direct competition for heating and, above all, for burning in power stations to turn the turbines that generate electricity. Thus as the price of oil fell in real terms so did that of coal, to such an extent that a large number of pits became “uneconomic” in the sense that the cost of producing coal from them became higher than the receipts from selling that coal; in other words, they ceased to be profitable (what the term “economic” really means in the context of capitalism.).

Under such circumstances the logic of capitalism decrees a single result: the unprofitable productive units must be closed. The then government — Labour under Harold Wilson — did not hesitate to carry out this decree. A Fuel Policy White Paper, published in November 1967. planned for a massive reduction in coal production as power stations continued to switch to relatively cheaper oil. As a result a record number of pits were closed in record time, devastating mining villages in South Wales and the North East especially, but affecting all areas to a greater or lesser degree. What the present government is planning is nothing compared to the butchery of the coal industry that took place in application of the 1967 White Paper. This was when Lord Robens, a former Minister in the post-war Labour government and Chairman of the NCB since 1960, was prompted to declare, somewhat belatedly:

I do not believe that in 1945 those of us who were nationalising these industries would have done it with so much enthusiasm if someone had told us then that they were going to turn into state capitalism (The Times, 1 April 1968).

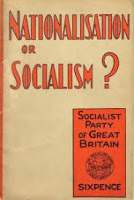

Of course the NCB did not “turn into” state capitalism for it had been so since its creation in 1947 — and someone did tell them at the time, as our pamphlet Nationalisation or Socialism? which exposed nationalisation as state capitalism, had come out in 1945.

But changing market conditions make nonsense of all attempts to “plan” production under capitalism. After the Arab-Israel War of 1973 and the closing of the Suez Canal oil prices began to soar as the OPEC countries exploited their quasi-monopoly position to the full. This meant that coal began to become competitive again; indeed that a number of the pits closed in the late 60s and early 70s as uneconomic would have been profitable again. But once a pit has been closed it can’t be re-opened. Responding again to the logic of capitalism as relayed by the forces of the market, the government — also a Labour government under Wilson — decided to change its energy policy and halt the decline of coal. This was the time — 1974 that the much-talked-of Plan for Coal was drawn up which promised a rosy future for the coal industry with job security for miners.

However, in another illustration of the planless nature of capitalism, 1974 also marked the beginning of the current depression. As the crisis deepened production fell: less industrial activity meant less demand for power and less demand for power meant less demand for oil. In addition, the measures taken to find substitutes for oil (such as nuclear power) began to bite over the years, helping to break the OPEC price ring. As a result of all these factors, towards the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s the price of oil began to fall, thus making it more competitive with coal.

The Plan for Coal was now seen to be too optimistic and an increasing number of pits became uneconomic. A first attempt was made to impose a new pit closure programme in 1981 but, in face of unofficial strike action in a number of coalfields, the government (by now Conservative under Thatcher) retreated. Subsequent events have shown this to be merely a tactical retreat to better prepare the next attempt. This came in the autumn of 1983 with the appointment of Ian McGregor, fresh from butchering the steel industry in the interests of profit, as Chairman of the NCB. One of his first acts was to provoke the miners’ strike at a time (the end of winter) and under circumstances (over three million on the dole, a re-elected government in its first year of office) favourable to the government, with a view to imposing a new pit closure programme.

The NUM really had no alternative but to respond by taking some kind of action. To passively accept McGregor’s diktat would have been a sign of weakness that would have been interpreted by the government and the NCB as an invitation to walk all over the miners, on other issues too. But the NUM’s National Executive should have realised that the pit closure issue was one on which neither the government nor the NCB could give in, even if they wanted to, since to keep open the unprofitable pits would be to defy the economic logic of the very capitalist system it is their job to uphold and apply. The most that could have been obtained on this issue was a temporary stay of execution or the keeping open of a token number of uneconomic pits.

A more realistic approach by the NUM Executive might have been to broaden the issues of the strike to other matters such as redundancy pay, pensions, working hours, holidays or wages as this would have allowed them to win something on these fronts in exchange for the retreat they were going to have to make on the pit closure issue. As it was the NUM, and in particular its President Arthur Scargill, chose to fight on the single issue of pit closures, which was a loser for them from the start. After a heroic 12-month strike by over 100,000 of its members, the NUM lost on all counts: the miners have come out of it with less job security than before (and with a weakened, divided national organisation) while the NCB now has a freer hand to sack workers than it previously had.

As a matter of fact this is a more usual end for a long strike than the relative “victories” achieved by the NUM in 1972 and 1974, when they essentially restored their wage levels of a few years previously. But then even if a group of workers “win” a strike they still remain exploited wage- labourers forced to produce profits for their employers.

In any conflict between employers and workers it is always the employer who is in the stronger position, for two reasons. First, because the employing class own and control the means of production and second because they control political power. In short, the bosses are richer and stronger than the workers. This does not mean that a group of workers can never win a strike but it does mean that they enter every such battle at a disadvantage. It also means that an employer determined and ruthless enough can always win — as the miners’ strike illustrates.

The miners involved in the strike will have learned that the police, the courts and the media represent the bosses, not working people. They should also have learnt the limitations of industrial action and that their real enemy is not so much their immediate employer, or the government of the day, as the whole capitalist system of which employers and governments are but cogs and which can only be overthrown by political action. As long as the employing class own the means of production and control political power the working class will always be on the receiving end.

Adam Buick