Tightening union law

Reform of trade union law continues to follow the pattern established early in the nineteenth century. Alternately the law is tightened by Act of Parliament (or by a new interpretation in the Courts) and the unions then do an electoral deal with one or other of the political parties to get it relaxed again. In this century the unions did a deal with the Liberals to obtain the 1906 and 1913 Acts, and then saw the law tightened against them by the Tory 1927 Act. This Act was repealed by the 1945 Labour Government, but the law was tightened again under the Heath Government’s Acts, which were duly repealed by the 1974 Labour Government. Since 1979 new restrictions have been imposed and more are on the way under the new government.

It is not that the unions want no trade union legislation. They want a law which recognises them as legal organisations (before 1824 they managed to exist illegally) and protects their funds against employers’ actions for damages and embezzlement by dishonest officials.

During the last Tory government (1979-83) certain forms of picketing were made illegal, and the law was altered so that after November 1984 ballots will have to be held to approve closed shop agreements. Also a new regulation was introduced into payment of supplementary benefit to the family of a worker on strike, which assumes that £13 a week strike pay is being received by strikers from their union whether or not they actually receive it, and deducts £13 from the benefit. (The strikers themselves cannot claim supplementary benefit.)

The new legislation to which the present government is pledged will require the governing bodies of unions to be elected by secret ballot, ballots every ten years to permit a union to have political funds, and ballots before strikes take place. It is not the declared intention of the government to make strikes illegal if a ballot is not taken, but if a strike takes place without a ballot the union will render itself liable to employers’ actions for damages. The election manifesto also proposed special “procedure agreements” for the essential services (nursing, water, gas, electricity supply) to minimise the likelihood of strikes

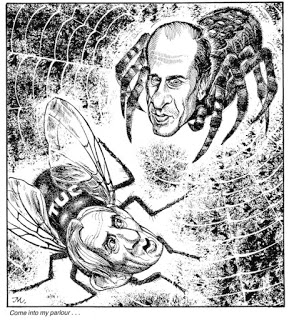

It appears that the main purpose of the new legislation is to threaten union funds and weaken the link between the unions and the Labour Party, thus hitting at Labour Party funds, eighty-five per cent of which comes from the unions. Counting on the fact that at the recent general election a clear majority of trade union members voted for the Liberal-SDP Alliance or for the Tories, Norman Tebbit, Minister for Employment, looks to ballots on union political funds to reduce trade union affiliation to the Labour Party. In addition, there is the threat that if the TUC refuses to discuss the issue with the government, legislation may be introduced requiring trade union members wishing to contribute to a political fund to “contract in” instead of the present arrangement under which objectors have to “contract out”. This was one of the features of the Tory Trade Disputes Act 1927 and its effect, along with the prohibition of Civil Service unions affiliating to the Labour Party, at once cut Labour Party income by a third.

While the law plays a certain part in the effectiveness of trade union organisation and strikes in struggles with the employers the emphasis given to it by union spokesmen is out of all proportion. More important is the extent to which workers are organised, and more important still, the “state of trade”: whether capitalism is in a phase of expansion, with profits running at a high level, or whether it is in depression, with heavy unemployment. Restrictive trade union laws have generally not prevented the growth of trade union membership, from about one in eight of the workers in 1900 to over half in 1977. Trade union membership continued to grow under Tory governments 1951 to 1964, and under the Heath government 1970-1974. It has been the depression which has reduced membership by over a million since 1979.

When capitalism is booming employers do not want the flow of profits to be interrupted by strikes and will be disposed to make concessions, with or without an actual strike. In a depression it is different. What impact can the union’s threat to close down a factory have when the employers themselves are about to close it down, temporarily or permanently, because the products cannot be sold at a profit?

The intended ballot before a strike takes place recalls the proposals made by the Labour Government in 1969 in the document “In Place of Strife“ issued by the Minister for Employment, Barbara Castle. While rejecting compulsory ballots in all cases, it proposed that the Minister should have power to order a ballot at his or her discretion and that 28 days should elapse before a strike could take place. In the event of the Minister’s order being defied, financial penalties could have been imposed on employers or strikers. In face of trade union opposition the clauses strongly objected to were dropped and a much modified Bill was never enacted owing to the defeat of the Labour Party at the 1970 general election.

The proposals in “In Place of Strife” and the present Tory proposals are both one-sided. They call for a ballot before the strike but say nothing about a ballot on ending a strike. When the Socialist Party of Great Britain, early in its history, urged unions always to have a ballot before a strike and another before the union officials could accept offered terms of settlement, it was in the interest of democratic control of union policy by the membership. At the same time we urged trade unionists to recognise the realities of the working class position in capitalist society. Power is in the hands of those who have effective control of the machinery of government, including the armed forces. If employers, with the backing of the government, consider an issue of vital importance and are therefore prepared to fight it to a finish, unions cannot hope to win. If a strike does not bring quick results the union should accept the reality of the situation, call it off and await a better opportunity. When the coal miners in 1926 continued on strike for five months they were doomed to defeat, and at the end they were bankrupt and witnessed the setting up of rival breakaway unions.

The reality of the political situation was pin-pointed in a curious way by Lloyd George when he was Prime Minister in 1919. Threatened with a general strike by the triple alliance of miners, railwaymen and transport workers he met their leaders and informed them that if they struck they would win, because “the Army was disaffected and could not be relied upon” (Times, 16 November 1979). He asked the union leaders if they were ready to take over the government of the country; which of course they were not, and the strike was called off.

For trade unions to contemplate strikes to overthrow the newly elected government is suicidal and a policy of despair. But it does not mean that there is no way out. They should recognise that while capitalism lasts, whatever government administers it, they are only fighting over and over again the defensive battles of the past two hundred years — and getting nowhere. We endorse what Marx wrote over a hundred years ago:

They ought to understand that, with all the miseries it imposes upon them, the present system simultaneously engenders the material conditions and the social forms necessary for an economical reconstruction of society. Instead of the conservative motto “a fair day’s wages for a fair day’s work”, they ought to inscribe on their banner the revolutionary watchword, “Abolition of the Wages System”.

In other words the only solution is worldwide socialism.

Edgar Hardcastle