Monuments to misery

Historians will no doubt argue for years to come exactly what is meant by the term “Industrial Revolution” and when this social change occurred. However, one can say that in relation to Britain, the term broadly applies to the tremendous technological development that took place in the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which transformed the means of production and, with them, every aspect of society. But of course, the Industrial Revolution did more than that. Its significance for the socialist lies not in the technological changes in the production process, but in the consequent development of the working class and the creation of a productive capability, previously unknown.

The working class were the new “slave” class. They were the people who would produce the wealth for the new society — capitalism. The urgent task still awaiting their attention, arises directly out of the Industrial Revolution — the harnessing of capitalism’s productive forces in the interests of all to banish deprivation from the earth for ever. For the socialist, this is not a question of techniques of production, but of social organisation.

New museums

In order to understand the nature of present-day society and why its seemingly insoluble problems remain, it is necessary to have some grounding in history. This is why the socialist will welcome the four new museums of the Industrial Revolution that have opened in Shropshire under the blanket heading of the “Ironbridge Gorge Museum”. Within easy walking distance of each other at Coalbrookdale on the banks of the murky river Severn, they trace the industrial development that took place in this area, with its natural resources of coal, iron and clay in particular.

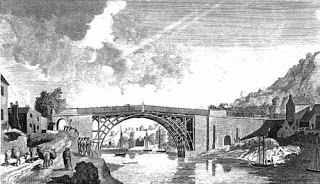

An attempt has been made, at least in part, to take the museums to the exhibits. Constructed on the sites where the developments illustrated actually took place, they concentrate especially on the late 18th century, when in effect, a new iron-age was introduced. The ironbridge itself, situated by the (now run-down) town from which it takes its name, is a remarkable product of the early industrial activity of the district. With the growth of trade and industry along the river Severn, industrial traffic across the river became heavier through the eighteenth century. The traffic needed a bridge somewhere near to the smelting and mining districts, but the technological problems this presented proved considerable. The barges travelling along the river needed clear passage and no obstruction could be allowed in the water. On the other hand, the steep banks made it almost impossible to build a bridge by the then conventional methods, especially since it would need to be very high to allow laden barges to pass beneath. The result was an iron bridge, which at the time must have seemed almost as fantastic as flying machines to the Victorians. Yet this world’s first ironbridge was eventually built; weighing 378 tons, with a span of 100ft 6ins, it was finally completed in 1781. Immediately it became a spectacle, with people (rich people anyway) travelling miles to see it. As the guide book explains: “To build a bridge in iron was not simply a matter of whim, fancy or ostentation, but the application of a new technology to the solution of a particularly difficult problem”. The bridge has been repaired and strengthened this decade, and should last another 200 years.

Iron Bridge, Shropshire c.1800

The museum sites are even more interesting and focus on work done in the area including mining. In particular, the development of the use of iron following the discovery in 1709 at Coalbrookdale that it was more efficient to use coke rather than charcoal in the smelting process, threw up the possibility of a tremendous increase in the production of iron. So the development of iron and related products is reflected in all parts of the museum sites. In particular the “open air” museum successfully recreates the atmosphere of the period. Much of the old machinery of production is preserved and restored on the sites where they were worked, and the museum is also importing historic pieces of machinery from other parts of the country, which would otherwise be destroyed. Here, the visitor can see the giant double beam engines known as “David and Sampson”. Built in 1851, these monsters were used to blast air into the furnaces. Originally powered by water-wheels, they were later adapted to steam power. The large volumes of air that they could blow’ into the furnaces enabled bigger works to be constructed and operated than had hitherto been possible. The original blast furnaces are also being reconstructed, as are various other mining processes, and the museum has also started the re-creation of a small town typical of 19th-century industrial Shropshire. When completed, it will be a lesson in history, far better than most books can provide.

The omissions

The museums stand as a tribute to man’s ability to harness nature’s powers and adapt them to his needs. But apart from one or two exceptions these exhibitions have a glaring omission. They illustrate the progress man achieved at a particular time — they don’t reveal the misery, the huge amounts of suffering this imposed on men, women and children. It would be quite wrong to romanticise the conditions of the majority of people in England prior to the Industrial Revolution.

There can be little doubt that pre-capitalist England was an easy life for the aristocracy, a comfortable one for a further small section, and pretty hard going for the majority. However there can also be little doubt that the start of the Industrial Revolution introduced the most appalling working and living conditions for the majority of people. A misery was imposed on the working class, the likes of which had never been known. And the sheer size of the event, and the hopelessness of the lives of the majority of people experiencing this “progress”, makes one shudder to read about it even at this distance. This failure to illustrate what was happening to people at the time of the Industrial Revolution, is the museum’s fault; perhaps they will remedy it in time.

In order to discover what it was really like for people who did not own the means of production during the Industrial Revolution, it is necessary to turn for guidance from the museums to the history books. And undoubtedly one of the best history books for this, is Volume I of Marx’s Capital. The history of the development of capitalism with its almost all-embracing inhumanity, is movingly documented by Marx. Large sections of the work are a plea to bring to a stop the totality of sufferings that the new developments had brought.

Horrific reading

Among the many things Marx does in this regard is to describe in detail (usually taken from government reports) the actual living and working conditions of the people operating the new technological marvels; and it is pretty horrific reading. But Marx also explains why this development resulted in such suffering. In brief, it was because the purpose of the new processes was not to benefit society as a whole, but only those who were receiving the increased profits the developments brought. Marx writes in Volume I of Capital (Lawrence & Wishart edition 1970) that: “machinery becomes in the hands of capital the objective means systematically employed for squeezing out more labour in a given time”, (p.412) A little later on Marx points to the contrast between earlier society (handicraft and manufacture) and capitalist society proper (factory production) when he writes:

In handicraft and manufacture, the workman makes use of a tool, in a factory the machine makes use of him . . . The lightening of the labour, even, becomes a sort of torture, since the machine does not free the labourer from the work, but derives the work of all interest . . . it is not the workman that employs the instruments of labour, but the instruments of labour that employ the workmen . . . the instruments of labour confront the labourer, during the labour-process, in the shape of capital, of dead labour, that dominates, and pumps dry, living labour-power, (p. 422/3)

What Marx is saying here is that at the time of writing, the technological developments had not been harnessed to satisfy the needs of all the people, but only the needs of the minority. In the meantime, these marvellous developments were being used to destroy all purpose in work for the majority of people.

It is this aspect of the Industrial Revolution the Coalbrookdale museums fail to bring out. And this is the most important lesson for the working class. For capitalism’s inhumanity in the relentless and frequently bloody drive for profits, continues to the present. Day by day, hour by hour, the life of the workers is drained by the engines of capitalist accumulation. Instead of the wonderful advances of Ironbridge and elsewhere being harnessed to the benefit of one free human race, technology is used to increase the exploitation of the majority in the interest of the minority.

Ronnie Warrington