For many, the years following Evo Morales’s 2005 election in Bolivia were marked by jubilation and hope. For Bolivia’s indigenous people, support for Morales appeared to be paying off. The poverty rate dropped from 59.9 percent in 2006 to 36.4 percent. Access for indigenous communities to electricity, sewerage and water service all grew.

Morales presided over an economy that has grown by an annual average of 4.6 percent since he took office, more than twice the rate for all of Latin America. After nationalising the country’s natural gas reserves, he pursued market-friendly economic policies and invested export revenue in social programs that helped lift more than two million people.

Now Morales faces growing opposition from the diverse ethnicities that made him Bolivia’s first indigenous president. After clashes with native groups over development, and constitutional manoeuvres to stay in office, across Bolivia, indigenous people are increasingly turning against Evo.

‘His way of thinking and his actions aren’t indigenous,’ said Gualberto Cusi, a former judge and ethnic Aymara, an Andean tribe from which Morales himself also hails. ‘He always said he would consult the people,’ said Salles, the former Conamaq leader. ‘Now he doesn’t.’

Two major indigenous rights organisations, Cidob and The National Council of Ayllus and Markas of Qullasuyu, left the Unity Pact. Government supporters began to stage what some described as coups within the organisations. Politics and loyalty to Morales began to matter more than the indigenous cause and pro-Morales activists said those organisations’ previous leaders were tools of American imperialism.

‘I have heard many debates in the UN where presidents condemn climate change but they never say – cowardly enough – what causes it. We say clearly that it is caused by capitalism,’ Morales declared in 2009.

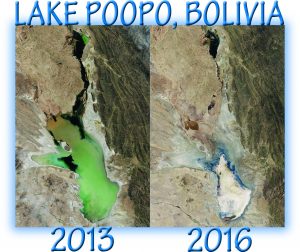

Lake Poopó, once Bolivia’s second largest body of water covering 2,400 sq km, dried up completely by late 2015. The government blamed climate change exclusively for the lake’s disappearance, allowing it to avoid taking any responsibility for the lake’s drying and ignoring the effects of irrigation schemes and water taken for mining which Morales is reluctant to regulate.

Morales has accused developed countries of pushing ‘colonial environmentalism’ in Bolivia when NGOs criticise the construction of a highway through protected ecosystems. The 190-mile (300km) road would cut through the Isiboro Sécure Indigenous Territory and National Park, known as Tipnis.

‘This is the beginning of the destruction of protected areas in Bolivia and indigenous peoples’ territory,’ Fernando Vargas, a Tipnis indigenous leader, explained, ‘Evo Morales is not a defender of Mother Earth, or indigenous peoples. He’s in favour of extractivism and capitalism.’

Opponents of the road say it will open up the park to mining and oil and gas exploration, as well as loggers.

Morales has also lost another pillar of his support. Historically the mining cooperatives have been allies of the President. With the global commodities downturn in prices such as in zinc, tin, silver and gold it has reduced the income of the miners and the miners want a larger share of the mining revenues. The pie is smaller for the cooperative miners’ returns. The pie is smaller for the state and its taxes. The cooperatives want the right to form partnerships with transnationals. As the Guardian put it (28 August 2016): ‘They want to be able to associate with private companies, which promise to put more cash in their pockets, but are currently prohibited from doing so.’

A cooperativista is willing to risk poor health and water pollution in the hopes of benefiting. With commodity prices well down the outlook is for fewer prospects for co-operatives to make a living — and thus more anger, discontent and unrest. An article in Dissident Voice reached the same conclusion as the World Socialist Movement:

‘…like many cooperatives in the US that arose out of the 1960s, they have turned into small businesses. Regardless of their initial intentions, cooperatives existing in a surrounding capitalist environment must compete in business practices or go under’ (our emphasis, dissidentvoice.org/2016/08/behind-the-bolivia-miner-cooperatives-protests-and-the-killing-of-the-bolivian-vice-minister/).

As we now see from the series of articles here on Latin America, capitalism is a global system and no matter how genuine politicians may be or how well-meaning their policies may be, capitalism has its own laws which must be eventually submitted to and which cannot be disregarded for very long. In Nicaragua, Venezuela and Bolivia, each nation may have encountered issues unique to them but all three shared one common problem – capitalism dominated their economy. Declaring that your government is anti-capitalist does not make it so and they are most definitely not examples of socialism or even aspiring to be.

ALJO

From Socialist Standard November 2018 article in Material World