What we’re dealing with is value and price and I would remind you that the only way you can test the validity of Marx’s theories or the theories of any other economist is to apply the test as to whether they satisfactorily explain what goes on in the modern world. We should ask the question for example; do Marx’s theories explain crises and wages and profits and unemployment as we see them around us today? If, and I’ve heard this argued, including on occasion by some people who knew something about Marx; if it is argued that Marx’s theories are irrelevant in the middle of the nineteenth century but they’re no longer relevant because capitalism has changed then we should stop wasting our time on Marx and go and look for somebody else’s economic theories to explain what is going on in the present world.

In this evening, what I’m particularly concerned with is prices, including the price of labour power, that is wages. For this purpose, it is necessary that you should have a clear idea of what the labour theory of value is. And if you do, if you get a clear idea of the labour theory of value, you shouldn’t have much difficulty with the critics who come along and offer various criticisms of the labour theory of value.

I would remind you by the way, at this point, as I’ve said before, you should read up something about this. The obvious sources are the early chapters of Volume 1 of Capital or Kautsky’s economic doctrines of Karl Marx and the two pamphlets, ‘Wage Labour and Capital’ and ‘Value, Price and Profit’. And if any of you are interested in the labour theory of value before Karl Marx, there was an article summarising it in the Socialist Standard in July 1934.

Now as I say, if you get a clear idea of the labour theory of value, you don’t have to worry much about the critics. And I’ll give you one or two examples. There is a popular economic textbook called Benham’s economics which is no longer written by Frederic Benham but by Professor Paish – in the revised editions, it also carries his name – Paish says that the labour theory of value must be wrong because it does not explain why picture by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot that – and in his words – ‘dashed off in a few hours’ sells for more than a painting by a mediocre artist which took several months to produce.

Now that’s a criticism that he says ‘that’s my only criticism’, he say ‘I just give one criticism of the labour theory of value’. He doesn’t think it necessary to give any others. He thinks this one settles the thing entirely. Well the whole of this is entirely irrelevant to Marx’s theory of value. In the first place, Marx devised his theory to study commodity production. As he says, you remember, in the opening paragraph of Capital. He was dealing with the everyday products of capitalism, that is things that are produced continually and continuously produced as in the factory system. He was not offering the labour theory of value for application to a unique and irreplaceable painting by an artist long dead. It has nothing to do with the labour theory of value.

Remember, by the way, of course, a unique painting by Corot or somebody else cannot be reproduced. You could have a machine reproduction of it. But that is not the same thing, that is an entirely different proposition. As far as the original painting is concerned, it can’t be duplicated or replaced. It ,therefore, doesn’t enter into the field of commodities that Marx was dealing with. Now to the extent that Paish was trying to bring out the difference between skilled labour and less skilled labour as apparently he was, he talks you see about Corot and the mediocre painter, Marx did,of course, deal with this. Marx did deal with the question that some labour is more skilled than others and I’ll come back to that later.

Also, Paish, as you notice, from the quotation doesn’t mention value at all, he says ‘it sells for more’. In other words, he was not dealing with value but dealing with price which would only be a valid criticism of Marx if, in fact, Marx had argued that value and price are the same things. That is to say, if Marx had said commodities sell at their value. If Marx had said that, then there might have been a slight relevance in Paish’s criticism, although as I say, Marx was dealing with commodities ,not irreplaceable paintings.

There is another critics, Robert Conquest, who criticised the labour theory of value on the ground that it would not explain the high price at which you could sell the oil, if an oil gush has suddenly popped up in your back garden, to which of course you had to give no labour. Well of course, here again, this has got absolutely nothing to do with Marx’s labour theory of value. The world’s oil supplies did not come from thousands of miraculous gushes springing up all over the place without labour. Royal Dutch Shell has spent, I read the other day, something like four thousand million pounds this year looking for oil, boring, refining it, all the rest of it. Now if oil could be obtained with hardly any labour, that is to say, if all the world’s oil supplies popped up in your back garden, the price would drop to a mere fraction of what it is now, in accordance with the labour theory of value. But Robert Conquest’s criticism you see has nothing whatever to do with the labour theory of value. Marx wasn’t trying to explain things like these.

There is another similar criticism, I think Louis Boudin mentions it, somebody threw up the criticism, why would, suppose you had a meteorite that came out of the skies and dropped on the Earth and it was a solid lump of gold and therefore you’d be able to sell it at a large amount, how would Marx’s labour theory of value explain this. Well, of course, Marx’s labour theory of value doesn’t have to. It wasn’t devised to explain the curious behaviour if meteorites do behave like this, it was to deal with commodity production.

So now, what is the labour theory of value?

To start with, it deals with commodity production. And a commodity is in the first place, something which is useful – that is to say, an article which has use value. If it isn’t useful, nobody wants it and it doesn’t enter into the picture. So you start with, a commodity has to have a use value, it has to be useful.

Secondly, it has to be produced for sale.

If you grow some vegetables in your back garden for your own use, those are not commodities. They are not produced for sale in the market. Whereas the typical capitalist product, the factory product, is produced not at all for the shareholders in the company but simply to be sold in the market.

So we’ve got to this far, commodities are articles that are useful and are produced for sale.

Next you want to notice, what is meant by production. It means that they embody human labour, the people have laboured to produce them and the amount of labour needed for different kinds of commodities reflects their relative value. In ‘Value, Price and Profit’ Chapter 6, Marx wrote this ‘a commodity has a value because it is a crystallisation of social labour. The greatness of its value or its relative value depends upon the greater or less amount of labour necessary for its production.’

And you want to notice a point here, this doesn’t mean that the longer it takes to produce a particular kind of commodity, that the larger its value will be. Because as Marx said if a commodity was produced by a lazy inefficient worker, it will take him much longer to produce it than if it is produced by a diligent and skilled worker. And you cannot possible have the same commodity with three different values. Suppose for example, one company could produce a standard chair in an average of ten hours and another company took twelve hours and the third company took fourteen hours, if you merely had to say how long did this take to produce and then take whatever that figure is, you could then have the same commodity having three different values. In this case, values related to ten hours, twelve hours and fourteen hours and of course that is impossible. A commodity can only have one value.

And the answer to this is that Marx didn’t say that it is merely the quantity of value required to produce a commodity that reflects its value but he said the quantity of socially necessary labour. And he defined it like this, this also is in Chapter 6 of ‘Value, Price and Profit’.

In saying that the value of a commodity is determined by the quantity of labour worked up or crystallised in it, we mean the quantity of labour necessary for its production in a given state of society under social average conditions of production with a given social average intensity and average skill of the labour employed.

Now you see how this is qualified.

What you are saying in effect is, if in a particular country at a particular time, the particular commodity under average conditions requires ten hours labour to produce, that is the quantity of socially necessary labour. And it’s only that, socially necessary labour that counts in respect of the value of the commodity.

The next point to have to notice is the one that I referred to in connection with Paish and his painting. That is skilled and unskilled labour.

Marx recognised of course that a man having greater skill can do in five hours what a less skilled man might take six or seven hours to produce. And his answer to that problem was to reduce all labour to its equivalent in simple average labour. He wrote ‘skilled labour counts only as intensified or rather multiplied simple labour so that a smaller quantity of skilled labour is equal to a larger quantity of simple labour’

Do you get the picture?

If you have a highly skilled man doing the job, two hours of his labour may be equal to three hours of the labour of a less skilled worker. In other words, Marx is saying you can reduce all of these to terms of simple labour and it is as it were units of simple labour that he is talking when he is talking about socially necessary labour.

And Marx adds that he said that, in practical experience, you know that this is being done all the time. The skilled labour is being reduced to simple labour.

Well, I might digress for a moment here to say that Bohm-Bawerk challenged this idea of reducing skilled labour to simple labour and if you’re interested you can find the question discussed in Hilferding’s book ‘Bohm-Bawerk’s Criticism of Marx’ translated and with commentary by Eden and Cedar Paul. Actually, I don’t think you really need very much about it, it was a highly abstruse point that Bohm-Bawerk went into and it revolved in fact around the actual words that were used in translation and Eden and Cedar Paul discuss this. But I think you can take it yourself, think of your own experience and think of the way in which in fact you know that the skills are different, the workers are different and you can see by practical experience how it is quite a valid proposition to reduce them to terms of simple labour.

In this connection I couldn’t find the thing today, but long long ago, one of the families engaged in building the railways in the man’s memoirs, The Diaries of Edward Pease, he was discussing the problem of taking workers by chance as it were, recruiting workers just as they came along and putting them to work and he said that it was his experience and other contractors experience that if you just take five men by chance, any five, you will find that the average skill of each group of five is almost identical. In other words, you’ve only got to go to a number of five and the differences cancel each other out where you merely take people purely by chance.

But of course, nowadays, a lot of firms don’t do this, I mean for all sorts of things, they try to select their people and try to take only the most skilled.

But now to come back to the labour theory of value, the next point is the one that’s caused a lot of trouble and it is this, what is the labour needed to produce a commodity.

Failure to understand it had led to all sorts of controversy and misunderstandings and some by people who thought that they knew what Marx was talking about. Actually, it was one of Marx’s most valuable contributions to economic theory, something that none of his predecessors had properly understood and a lot of people still do not understand it.

There was and still is a widespread belief that the labour needed to produce a commodity is only the labour in the final stage of production. If I give a kind of examples, they are these; this would assume that bread is produced in a bakery; and motorcars are produced in the assembly plant; and that electricity is produced in the power station; and that food is produced by men on the land.

Now in popular language all of those statements would pass, I mean nobody would question it. But from an economic point of view, every one of those is completely invalid. But you read your newspapers and you will see they are turning up every day. People including economists are still using this kind of language about production and the way it is carried on.

What Marx showed is that the labour needed to produce a commodity includes not only the labour in the final stage, that is the labour in the bakehouse, or in the power station or on the farm, but the labour required to produce a commodity also includes all the previous labour, to use Marx’s term, the labour crystallised in the raw materials, the machinery, the buildings, the fuel needed to drive them and so on. Now that labour, that crystallised labour is transferred in the course of production from the raw material and from the buildings and the machines to the commodity as it is being produced.

So to come back to our kind of examples, the labour needed to produce loaves of bread includes not only the labour of the workers in the bakery but the labour of the workers who grew the wheat in the first place, reaped it, transported it to the flour mills, the workers in the flour mills who milled the wheat, and then finally it comes to the bakehouse, but then there’s also the labour of the people who built the bakehouse and the machinery and the fuel that drives it and so on.

So you’ve got to get this conception that all the labour is socially necessary labour that goes to make up a commodity and if you forget this, you see, if you start looking at commodities as if they’re only produced in the final stage, you can get all sorts of quite impossible results as you will if you keep your eyes open on newspapers and watch what the city editors and what the economists say, you will find they are walking into this sort of trap time and time again and getting into arguments with each other as to what productivity means without ever understanding it.

Again in ‘Value, Price and Profit’ Chapter 6, Marx says this ‘in calculating the exchangeable value of a commodity, we must add to the quantity of labour last employed, the quantity of labour previously worked up in the raw materials of the commodity and the labour bestowed on the implements, tools, machinery and buildings with which such labour is assisted.’

Value can change

I now want to make another point about value and that is that value can change. Having explained what is meant, by the value of a commodity and why different commodities have different values, we have to look at the way in which the value of a commodity can change not merely downwards, which so speak everybody knows, but it can also change upwards.

Suppose you have two commodities, one of which takes ten hours socially necessary labour to produce and the other takes twenty hours. Well, the second’s value will be twice as much as the value of the first. Twenty is twice ten. But now suppose that some technical change takes place in the productive process so that the first commodity which has been taking ten hours socially necessary labour to produce, suppose it becomes possible to produce it with five hours socially necessary labour. You will now see that the other commodity which takes twenty hours is no longer has twice the value of the first, it has four times the value of the first because the first one has dropped from ten hours to five hours and the other one has remained at twenty hours and that sort of process with individual commodities, not as violently as the figures I’ve given, but that kind of change is going on all the time. In other words, there are always technical changes taking place which bring in usually quite small changes in the amount of labour required to produce a commodity and if you are looking at each individual commodity, this lowers its value relative to other commodities.

But as I said, change doesn’t have to be downwards, it can sometimes be upwards. You take the familiar example of coal. A hundred years ago when coal was mined near the surface, the amount of labour required to produce a ton of coal was comparatively small. As mines have got deeper and deeper and they have to go for less accessible seams, there is a tendency for the amount of labour required to produce a ton of coal to increase. You will see this incidentally reflected in the price of coal. It’s obscured of course when you’ve had all prices rising, but if you look at the price of coal, you will see that it’s risen abnormally since 1938, abnormally in relation to the price of other commodities.

Now I want to say as I said with regard to Professor Paish that commodities do not have to sell at their value and, in fact, most commodities do not sell at their value. But nevertheless, if the value of a commodity is substantially reduced, in other words, if the number of hours socially necessary to produce it is reduced, this will reflect itself in the price of the commodity and works in the opposite direction. You see in the case of coal and some other things where the value is rising because more labour is required, it will show itself in an abnormally large rise in prices.

I now want to come to the question of changes of prices due to other causes, in other words, nothing to do with value. You have to remember this because Marx’s Labour theory of value primarily explains what value is and how it’s amount is arrived at. But Marx never took the view that that’s all you need to know to understand the movement of prices. Paish thought that Marx was saying that commodities all sell at their value which of course Marx was not. And I shall deal later on with Marx’s formal relationship between market prices and value. What I want to deal with at the moment is changes in price which have nothing whatever to do with value. Now the first lot of these is fluctuations of supply and demand. If I may just drop it on you, he said to you ‘I am saying on this page that commodities sell at their price but if you read my footnotes you will see that I’m going to say something different later on,.’ That’s the general picture.

First of all, there are fluctuations due to supply and demand.

First of all, there are fluctuations due to supply and demand. In other words, if there is a sudden drop in the supply or a sudden increase in the demand, it will change the price. If the supply falls, the price shall go up, if the demand increases, the price will go up, if the supply suddenly increases the price will go down and so on. I mean you can see this sort of thing happening, I know one place where you used to be able to see it. If you watch fruit stalls, say around Leicester Square on a Saturday evening on a hot day, just before the time they’re going off, they’ll flog you all the stuff at, trying to get rid of it at any price, or when there’s storm at sea and fishing boats can’t go out, fish prices will immediately rise, immediately these are fluctuations.

Well, what Marx pointed out was, and you see they’re not due, the mere fluctuations, they’re not due to a change in value. What Marx pointed out is you’ve not only get day-to-day fluctuations, but you have another lot of fluctuations you have to remember, and that is the fluctuations of price that go through a whole of a cycle of expansion, boom, crisis and depression. In other words, you, it’s no use saying what is the price of something today, to get its relation to value, you’ve got to look at how the prices change over a whole cycle. In general, of course, all prices go up when capitalism is booming. And whenever there is a crisis they come down again. Well, Marx said this is a fluctuation that you’ve got to bear in mind with regard to all prices and you’ll find that not only deal with in Capital, you’ll find that he dealt with it briefly in ‘Value, Price and Profit’.

For example, in the nineteenth century, from 1820 to 1914 when there was no inflation, you nevertheless got rises and falls in prices. In a boom you got prices rising , retail prices rising, somewhere within a range of about twenty five percent and in the depression you’ve got them coming down again. Wholesale prices are much more volatile and they fluctuate much more wildly. But remember that Marx showed, and I’ll come to it later, the relationship between value and prices, but over and above that, he had these fluctuations that you’ve got to bear in mind.

But you’ve also got to remember a particular kind of fluctuation in price, not due to a change in the value of commodities but to a change in the value of gold. And it can only happen when there is a gold standard, in other words, in the nineteenth century in this country when currency was tied to gold. When it was tied to gold and the law said that a pound sterling, a sovereign contains approximately a quarter of an ounce of gold, what the government was saying was that gold is four pounds an ounce or thereabouts. And if the government said that every sovereign has got to contain approximately a quarter of an ounce of gold, that’s tantamount to saying that the price of gold is four pounds an ounce and it stayed there with very very minor fluctuations.

But the reason why gold came to be the universal money commodity was that its value does not change much, but nevertheless towards the end of the nineteenth century a new process came into use for extracting gold from ore which cheapened gold, it reduced the amount of labour required to produce an ounce of gold and the effect of that was to put up the price level.

Now some of you may be wondering at this, all you’ve got to remember at the moment is, if you have a gold standard, if the currency is tied by law to gold and there’s fully convertible so you can always change your paper into gold or your gold into paper at this ratio, one pound is a quarter of an ounce of gold, if you have that system, if the value of gold falls, all other prices go up and if the value of gold rises, all other prices go down and you just remember so to speak that is worked contrary-wise. But if you think about this, you’ll see why in fact this must happen. And it must happen because the law said that whatever the value of gold may be, a gold is always four pounds because each pound is a quarter of an ounce weight of gold. And again remember this has no relevance whatever to the present situation because the currency now is not related to gold in any way whatever and so this sort of situation couldn’t happen. I mean the variations in the price of gold are not going to cause a change in the price level as they could when you had a gold standard.

Another factor Marx pointed out which affects prices and had nothing to do with value is monopoly. Where there is a monopoly, monopolies can, of course, put up his prices. In this country, for years now, we’ve had a monopoly in tobacco and alcohol, monopoly created by the government so you can have an artificially high price for cigarettes and alcoholic drinks and the government can cream off the bulk of it in taxation. But it has no relation to the value of the commodity. So in general, you remember that where there is monopoly you can have a price level not related to value in any realistic sort of way.

And, of course, in recent years you can have the opposite. You have the opposite where you have government subsidies. For years now the British government, they started it in the Second World War, they paid subsidies to keep the price of food down and they paid subsidies for house building. Well what in effect is happening, the government steps in and they pay the farmers to sell their food below market prices or they pay councils to build houses and let them below market value. But here you see, you’re getting a price level which is below what it would be under market conditions and this may be something that you have got to bear in mind.

Another point to remember is this. Marx said that because commodities have value, they have a price because price is the monetary expression of this. Marx did not make the converse statement, although a lot of people think that he did! Marx did not say that anything that has a price must have a value but a lot of people think he did, including many of these critics. Marx didn’t say this because he pointed out there are some things which have a price but are not the product of labour and therefore not commodities and have no value.

Land is one of them, land isn’t produced. You can’t produce more land in a factory by application of human labour. It is not a commodity, but land has a monopoly price. And so again you must remember that Marx, all the time, was dealing with commodities, the things that are normal products of capitalism that are useful, that are produced for sale and are produced by the application of labour power.

And this, of course, covers the example used by Paish about the painting by Corot or any other unique painting of a dead artist. They have a price but they have no value, I mean not value because they’re not commodities. I mean they’ve long passed out of this, or at least they were never in it, they were never in the position of being able to be reproducible like a motor car in a factory.

Incidentally, when Paish raised this question of Corot and talked about Corot dashing off a picture in a few hours and a mediocre painter taking months or whatever it was to do it, Paish doesn’t seem to have noticed that, well he doesn’t tell you, he doesn’t say that Corot did it in a few hours and a mediocre painter took several months to do precisely the same thing which of course would enter into it. But also he doesn’t seem to have noticed that in the modern art world, people will pay for a name. They will pay large sums of money for a Corot or Rembrandt even if it happened to be a pretty poor specimen of painting. In other words, it’s the name they buy for prestige sort of reasons. However, that is by the way.

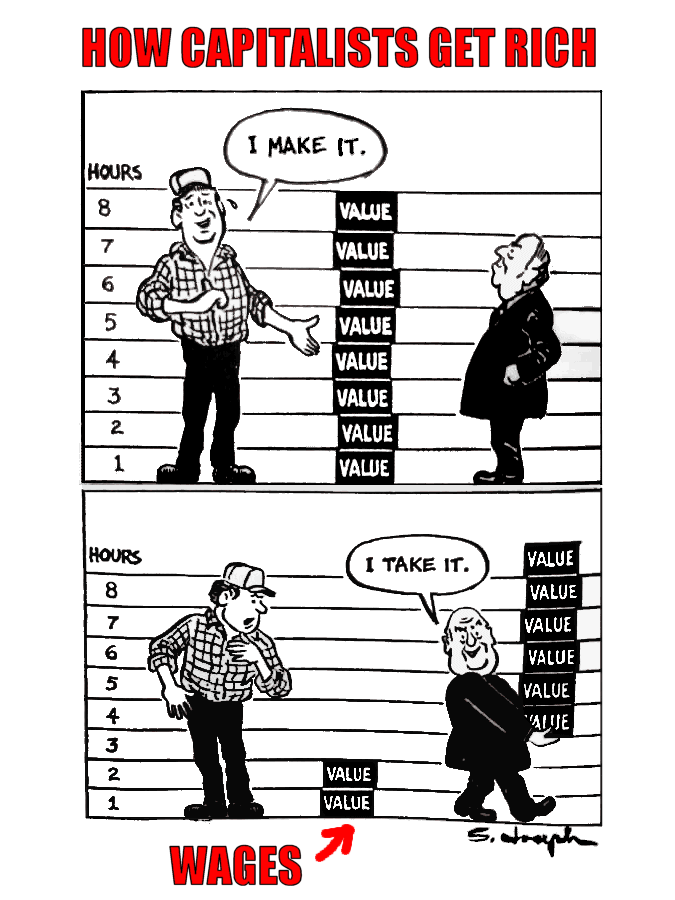

The last point about the labour theory of value, another contribution of Marx, an original one was that Marx’s conception that labour power is a commodity governed by the same laws as other commodities, in other words, that wages are prices. Marx, his predecessors Adam Smith and Ricardo didn’t see this, Marx did see it and it is of the utmost importance. Other economists before Marx and since have taken the view that when the worker goes and bargains for a job and agrees to work for forty hours a week, that what he has done is to sell forty hours labour to the employer. Marx pointed out that this is quite untrue, that what the worker sells is not his labour but his labour power, his mental and physical energies. And that what the worker does is to sell his labour power to the employer for a week, an employer then sets it to work.

But labour power has the unique quality that it can produce a value greater than its own, in short, to take the example of the week because it is simple, suppose a worker is doing a five day week, it might be true and it would be proximately true in some trades, that in three days, the worker would have created value equal to the value of his labour-power and of course the employer has bought his labour power for the week. So although after three days the workers has added value equal to his labour power, the employer has him going on working for the other two days when as Marx said he is giving unpaid labour to the employer, the employer is getting labour that he hasn’t paid for and this is a surplus and Marx called it ‘surplus value’ out of which come profits.

Incidentally, once you get this idea that labour power is a commodity and therefore wages are a price and something the worker sells, you can see how wrong are all of these people which includes I suppose about three quarters of the politicians and economists, these people who try to explain inflation by saying that wages have gone up. You see once they could get the idea into their head that wages are prices they could then see that if something happens and that something is an excess issue of the currency which raises the price level generally, wages being prices will go up with other prices. And so that it is quite false for them to separate one price from another price, to say the reason why other prices have gone up is because this price has gone up. If they’re all prices, they go up together. And this is, of course, the actual fact of the situation.

The value of labour power can change the value of other commodities but with some differences. Labour power is embodied in the worker and the worker can organise and can show resistance and things like this where of course, inanimate objects can’t do this. So the value of labour power does not have to be the bare physical minimum of existence, although, in certain circumstances, it might be and as Marx pointed out it contains a historical and what he called a moral element by which he meant that history, historic development, governs what the level of wages may be and various other elements enter into it, climate and things like this. But Marx emphasised the fact that the value of labour power can change. It can fall and it can rise. And over the last hundred years, both in the nineteenth century and since, over any longish period, real wages have been rising, not very much, say one, one and half per cent a year, that sort of thing in this country.

And on this question of the way labour power can change its value, you ought to look up Chapter 17 in Volume I Capital called ‘Change in magnitude in the price of labour’ also Chapter 6, ‘the buying and selling of labour power’ or ‘Value, Price and Profit’ Chapter 14 where Marx summarises all his views. And it’s very important to notice that when Marx talked about lots of tendencies that affects profits and wages, he finally came down, he summarised in ‘Value, Price and Profit’ and said ‘in the last resort, the way the product is divided into profits and wages depends on the powers of contending forces’ in other words it’s a struggle going on all the time and as it were sometimes there is an advantage comes to the worker and sometimes to the capitalist.

When there is a lot of unemployment, of course, the advantage is on the capitalists’ side, more than it is otherwise.

Whether value and price are identical.

We now come to this question, the basic one as to whether value and price are identical. So far we’ve been dealing almost entirely with value. There now comes the question of what is the formal relation of market prices to the value of commodities. And some students of Marx have got into difficulty by assuming that Marx was saying that value and price are identical and that commodities sell at their value and to prove their point, they will actually quote passages from Capital where Marx as they say said this.

They’ve read them carelessly! They haven’t noticed that what Marx said to them all the time, he did indeed use examples showing commodities selling at their value but they haven’t noticed that it was the way Marx builds up his case but he tells you so. He tells you in Capital the way he’s building up his case, he said we’re taking first a simplified proposition in which I’m assuming that value and price are the same and then he said later on I’ll deal with the real situation.

You will find for example, its in Volume I of Capital, Chapter 7, section called ‘rate of surplus value’, Marx gives some examples of value and price which are assumed to be the same. But there’s a footnote which says this, the calculations given in the text are intended as mere illustrations. We have in fact to assume that prices equal values, we shall have a see in Volume 3 of Capital that even in the case of average prices, the assumption can’t be made in that very simple manner and in fact then Marx in Volume 3, went on to show what is the real relationship between market prices and value.

And it’s a rather difficult thing that I mean if you read it up in one of the available places, you’ll get the hang of it and it is this, that there are some commodities whose prices are permanently above their value and there are some commodities whose prices are permanently below value without there being monopoly to put them out. You can forget monopoly in this connection and forget the fluctuations. That there are some commodities whose prices which sell permanently above their value and there are some which sell permanently below their value.

Now you will remember, I pointed out that the labour embodied in a commodity is of two kinds.

First, you’ve got the congealed labour that is transferred from the raw materials, the machinery, the building, the machines in the commodity and which doesn’t change in quantity. It’s a mere transferic transference. And you’ve got the second kind which is the labour which comes from the application of the labour power of the employed workers in a company. Now there the live workers in a company, their labour isn’t congealed as it is in the machine, they’re actually working and they create surplus value. In other words, they create a value greater than their own.

Now if all branches of industry developed uniformly, this problem wouldn’t arise. If for example, you could say, that for every million pounds of capital invested in whatever industry that the amount of it which would be devoted to machinery and the amount of it which would be devoted to employing live workers would be the same, this problem wouldn’t arise.

But capitalism has not developed like that and you have got in modern capitalism, some industries in which to use Marx’s phrase, there is a high organic composition of capital and some in which there is a low organic composition of capital. And if you want like to use the modern jargon which is I think its quite useful, the modern jargon is to call them capital-intensive industries what Marx called industries of high organic composition and labour intensive industries were industries of low organic composition.

And if you want a couple of examples, the telephone service is capital intensive, it has an enormous amount of capital invested in it in relation to the number of workers. The postal service is labour intensive, it’s an industry with low organic composition because it’s got relatively little machinery and so on and an enormous, very large number of workers. Now the coal mines, by the way, used to be labour intensive, they are now capital intensive. The new Selby pit which is due to open this month, they’ve spent six hundred million pounds on it before they’ve mined a single ton of coal.

Now a hundred years ago, miners would go out with a pick and shovel and clear away some of the top surfaces and start mining coal. Now it’s a capital-intensive industry and they happen to have an enormous investment in constant capital before the workers can get to work actually getting out the coal.

Now remember this, surplus value is created entirely by the workers employed in a company. Surplus value is not created by transference of congeal labour from a machine to a commodity, but solely by the living, by the workers employed. Now if commodities sold at their value, then the postal service which has a large number of workers would turn an enormously greater profit than the telephone service which employs only a relatively small number of workers.

And Marx drew attention to this. And he said and I’ll quote from Marx , this is in Volume I in the section ‘Rate and the amount of surplus value’; ‘this law obviously conflicts with all experience based on the appearance of things. Everyone knows that a cotton spinner who; when we reckon out the proportional allotment of his aggregate capital; is found to have a comparatively large amount of constant capital and a comparatively small amount of variable capital, does not for that reason pocket less profit or surplus value than a master baker who sets in motion a comparatively small amount of constant capital and a comparatively large amount of variable capital. For the solution of this apparent contradiction, a great many intermediate terms are needed,’

Now you see what Marx is saying. At the time he wrote, the master baker had not been mechanised, it was a labour intensive industry. The cotton spinners had been mechanised, in other words, they had much of their capital invested in machinery and a relatively smaller number of workers. Now if their commodities sold at their value, the one with the largest number of workers would make the largest profit. Therefore, you’d get the odd situation of the master baker, in this case, making a big profit and the cotton spinner making very little. As Marx says this is contrary to all experience.

It’s only later on that he will explain it. This was called the great contradiction. Critics of Marx said, they said, there you are, Marx drew up a labour theory of value and the Volume I of Capital based on the idea that commodities sell at their value and then when he had time to look at it further and he produced Volume 3, he had to throw it all overboard and had to produce a quite different theory. They have overlooked the fact that the passage I am quoting to you is from Volume I. In other words, Marx already knew the problem and he already knew the answer when he wrote Volume I. All he is saying to you is before you understand my solution, you’ve got to understand a good deal more about the way capitalism works and about the nature of the theory of value.

Again if I may refer to sources, you could read Engels preface to the 1884 edition of Volume II of Capital. You’ll find it in Boudin’s Theoretical System of Marx in Chapter 6 and it’s called ‘The great contradiction’ or you’ll find it in Kautsky’s ‘Economic Development of Karl Marx’ in Chapter 3 or of course in Capital Volume 3 itself.

Let me go over this again, with an illustration to see that you actually get the problem. Suppose you’ve got two companies with the same capital invested a million. And one in an industry of low composition of capital, that’s labour intensive, the other in an industry of high composition of capital, that’s capital intensive. Now take Company A which is labour intensive, invest a million pounds, has only a small proportion invested in machinery, constant capital, and employs five hundred workers. And take the other company and also invest a million pounds but it’s in a capital-intensive industry, it has most of its investment in machinery and so on and it only employs a hundred workers. So you’ve got two companies, both invest a million pounds, one employs five hundred workers, the other employs only a hundred workers.

Now since surplus value is created by the workers, the first company will be producing five times as much surplus value as the second company. And on that basis the first company might be, if commodities sold at their value, the first company might be making a profit of twenty five per cent, while the second company only made five per cent. Well what Marx pointed out was you can’t have such a situation that if you did have one lot of industries producing a profit of twenty five per cent and another only five per cent, capital would flow into the twenty five per cent interest, new people would move in to reap this rich harvest and no capital would flow into the other one where it’s only five per cent with the result that prices would adjust themselves. One lot of prices would go up, the other lot of prices would go down and you’d end with the situation where both companies were making say fifteen per cent on their capital. You cannot have a situation where one lot could be making five times as much profit as the other.

And the solution to the problem is, that under-developed capitalism, the commodities producing in the industries of low capital composition, that’s the labour intensive industries sell below their value and the commodities produced in the industries of high capital composition, the capital intensive industries sell above their value. You then bring the two sorts of things in line.

Lastly about surplus value, remember Marx’s conception. The capitalist in a particular company does not in fact get his profit out of his own workers, that you’ve got to have the conception of the whole of capitalism say in a particular country or a particular time producing a mass of surplus value. And that mass of surplus value which is produced by the whole lot of the workers comes down to different companies on the basis that each thousand pounds of capital invested get roughly the same sort of return. You don’t want to push this too far because obviously as you know there are other factors that enter into it but you there is this tendency for the rate or return on every thousand pounds of capital to be somewhere the same. The idea of the equal rate of profit, no matter what the industry is. But, of course, what goes with this is, you must have some commodities selling permanently above their value, and some commodities selling permanently below their value.

Now, Marx’s answer to this, and I’ll read out Marx’s words first before I come to the definition of them. In place of the simplified version Marx used when he was illustrating the thing at the beginning of capital of saying look I’m assuming here that commodities sell at their value, Marx put forward his final complete proposition which was that market prices do not fluctuate about value, they fluctuate about what Marx called the price of production. And the price of production is the cost of production plus the average rate of profit. Except that where there is monopoly, in the case of land, market prices will fluctuate something above production.

Now at first glance, you may fall into the error made by a lot of Marx’s critics and say look Marx obviously didn’t know what he was talking about. He goes and produces three volumes of capital to show that his theory is different from the theory of other economists and then he ends up by explaining market prices and profit in the language used by the ordinary capitalist concern. But of course, Marx wasn’t doing anything of the kind!

They had overlooked Marx’s definitions of the terms he used. When Marx was talking about price of production, he didn’t mean what the capitalist means by price of production, or when he talked about cost of production or the average rate of profit. Marx defined all of these carefully in terms of the labour theory of value. His cost of production was the cost in terms of the value that transferred into the commodity. And he termed his average rate of profit, he worked out his average rate of profit he’d gain in terms of the labour theory of value.

As I’ve already pointed out, if there was a higher rate of profit to be found in labour intensive industries than in capital-intensive industries, capital would as I said would flow in to the one where the profit was high and would not flow into the one where it was low so the whole thing adjusts itself through the ordinary competition of the market until you get a situation were wherever the capitalist invests his thousand pounds, he will expect to get roughly the same average return on it. And as I said, this forces down prices in one group of industries and forces up prices in the other. And the net result is that you have market prices which quite apart from fluctuations from day to day are permanently above value and others were they are permanently below value.

Kautsky in his ‘Economic Doctrines of Karl Marx’ puts it like this, it’s on page 89, ‘the prices of most commodities permanently deviate from their values inasmuch as the prices of one half of those commodities are permanently as much below their values as those of the other half are above their values.’

So I repeat the criticism of the labour theory of value based on Marx’s alleged great contradiction are quite baseless. The theory is a comprehensive one and so far as any theory can be proved in a textbook, Marx gives a very adequate demonstration of it.

One other point because I’m coming to the end.

All the way along, I’ve talked about commodities as things, and so did Marx, but Marx recognised that while it is true of most things, in other words commodities are mostly tables, chairs, motorcars, ships, aeroplanes, Marx recognised that there are some commodities which are not like that. The one particularly mentioned was transport.

See transport is a commodity, but transport is consumed simultaneously with its being produced, there is never an object that you can see which is transport but why its important is this. That in the production of commodities necessary transport is socially necessary labour and therefore adds to the value of the commodity. And there are some other commodities which you can treat in the same sort of way as transport. In other words, consume simultaneously with their production.

Again, one other point to remember, value is created in what Marx called the sphere of production which includes necessary transport. Outside the sphere of production, surplus value is not created, it is not created in the circulation process which you mustn’t confuse with transport, in the circulation where the capitalist is realising his profit, where the commodities are bought and sold and so on. That is outside the sphere of production and no surplus value is created in them, in that sphere.

So of course, labour in that sphere, does not create surplus value. What the labour of the bank clerk and the insurance clerk does for his employer, of course, it helps him to realise his profit. But the worker doesn’t create it. He’s exploited there in that he, like the workers in production, he’s giving unpaid labour, but no value is created in that sphere.

Lastly, by the way, why should we accept Marx’s theory of value as legitimate one. And I put to you the question at the beginning. Does it explain what goes on in the Modern World? And I would say that if you look around in those areas where you can test it, you can see that Marx’s theory of value has stood up very well. For example, because Marx relates value and ultimately price to value in accordance with the amount of labour socially necessary to produce different commodities, there is a certain stability about the price of commodities, that you can accept on the basis of the theory of value.

But people who don’t accept a labour theory of value find them very difficult to explain. You will often come across economists who do not believe that gold has any value, that it’s a purely artificial one, it’s very difficult to explain how they arrive at it, but I think I quoted last time, a BBC Radio 4 expert who said gold has no intrinsic value.

Now over the centuries or go over the two centuries of capitalism, you can see a certain consistent relationship between the price of a pound of coal, a pound of bread, a pound of silver and so on. They don’t change places. They may approach near to each other or get further away, but there’s a certain consistency about this. Well, you see on the basis of the labour theory of value, this is understandable. In other words, the amount of labour required to produce these commodities is very different. It requires ever so much more labour to produce an ounce of gold than to produce an ounce of coal and the same with the other things. So you’ve got this in favour of the labour theory of value.

There is something else in its favour, of course, it is all very well for an economist to come along a give you sort of psychological explanations of value, but the workers who actually work and produce things, actually know how they’re produced, they know that they contain value. They know that wealth is not created by people who work in offices, write figures in books and things like this. But this again is something to be said in favour of the labour theory of value.

But one of the strongest arguments for the labour theory of value is inflation. Marx’s explanation of inflation based absolutely entirely on the labour theory of value, does explain inflation. It does explain what has happened in the past and what is happening now. And all of the other economists are completely in the dark about it. That include both the Keynesians and of course Milton Friedman the monetarists who do not understand, although they, Milton Friedman so to speak gets halfway there, they do not understand what inflation is caused, or how to solve it, whereas, on the basis of Marx’s theories, inflation so to speak is an open book.

If you look at a book called ‘A History of Economic Thought’ by William Barber [and I think it’s a Penguin publisher], Barber goes over the labour theory of value of as Adam Smith, Ricardo and Marx and gives various criticism of them. And he makes this statement ‘it has become fashionable for modern economists to abuse any labour theory of value.’ In other words, what he is saying is that since Marx, practically all of the economists have said look you don’t want Marx’s labour theory of value, you don’t want Ricardo’s, you don’t want any. You don’t need a labour theory of value.

It is very interesting therefore to see what has happened in the case of William Rees-Mogg of the Times who having been a Keynesian for years and found it didn’t explain inflation and having done some study to try to understand it first came to the conclusion that the way to cure inflation was to go back to the gold standard which would, that would cure inflation alright, but quite recently, a month ago, he had another article, where he said, that he realised now, that you cannot explain prices without a labour theory of value. That you must have a basis for prices, that it’s no use thinking as admittedly many people do, that prices are just what the seller chooses to fix them at. You’ve even got the term, I don’t know if you’ve got it over here, but you’ve got it in American economic textbooks, where they said that prices had come to be fixed administratively. In other words, in every company, didn’t have to worry about anything else, they just fixed their price wherever they liked to choose it. Well of course, this is all nonsense. It’s interesting to see Rees-Mogg having does his homework and saying look I’ve now come to the conclusion that you must have a labour theory of value to explain prices and he’s gone back to Ricardo’s. And if he goes on another ten years, perhaps he’ll discover that Marx theory of value was an improvement on Ricardo’s.

Incidentally, by the way, there have been a number of people including people who call themselves socialists and some have even called themselves Marxists [Joan Robinson’s An Essay on Marxian Economics (1966) http://digamo.free.fr/robimarx.pdf ], who’ve taken the view that the idea of exploitation and surplus value can be picked out of Marx and used, stood on its own feet and that you don’t need a labour theory of value to back it up. In other words, they’ve repudiated the labour theory of value, they’ve said you know it’s out of date. Well, I think it’s absolutely illogical, the idea of surplus value arises absolutely out of the labour theory of value and you cannot have, you cannot take the things apart and say we’ll have the surplus value idea, but we don’t want the labour theory of value. And anyway they have never succeeded in showing where the labour theory of value is inadequate except by the irrelevant sorts of criticisms like the one I quoted from Professor Paish.

With this last point, see Marx completed theory of value is that commodities sell at their price of production which means that some of them permanently above their value and some of them permanently below their value. It’s an interesting question, can you prove this?

Well, you can show, you can read Marx’s exposition of it and the evidence he gives in it’s favour and so on and say alright, that’s fairly satisfactory. But if you come into the actual world and say, is it possible to go out in the market and say look, look at the current price of bread or the price of motorcars or something like this and then to examine this and show in fact they are selling at their price of production as defined by Marx.

I know some people who’ve tried to do it. All they’re really doing is guessing, I know no way whatever in which it can be done because the information simply is not there. The information is not available in Marx’s terms to show how much capital is necessarily used in producing bread or motorcars or what the average rate of profit is in Marx’s terms or any of these things. So all I can say is it can’t be proved or it can’t be disproved.

But I would say this, that it seems to me to be a very reasonable proposition in itself and also it of course it does reconcile the labour theory of value which the actual prices in the market and if you read Marx’s exposition of it, I would say that it’s a very reasonable sort of proposition.

Lastly, I don’t know anyone who’s offered an alternative which is as good. So in other words, it stands on its merits in the real world. But even apart from that, there are various other things, in particular, the inflation argument which puts Marx right above all the other economists. In other words, Marxism knew how to explain inflation and none of the other ones can and Marx explained it on the basis of the labour theory of value.

Edgar Hardcastle

February 1980