When Labour Ruled (3)

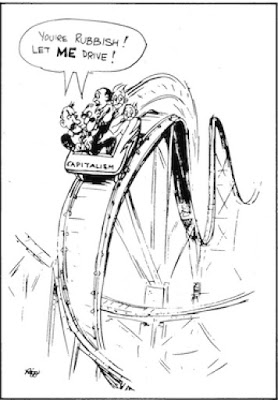

In their wildest dreams—and some of them have been pretty wild—the Labour Party could not have hoped for more auspicious circumstances in which to contest a general election than they had in February 1974. Quite simply, the Heath government handed them victory on a plate, liberally garnished with enough propaganda material to satisfy the hungriest opposition. The Tories had won power in 1970, against most expectations, with what seemed a clearly-defined policy on unions, industrial disputes and state investment in industry. These were quickly modified, or abandoned. or applied with such purpose that the country was sunk into the misery of the Three Day Week—and that over Christmas.

In contrast to the Tories’ apparent yearning to return to the days of the Tolpuddle Martyrs, the Labour Party under Harold Wilson could offer the guarantee that their close relationships with the unions would get the factories and the power stations working again, the street lights and the television sets on. and the grateful workers co-operating by moderating their wage claims. What was surprising was that the Labour Party only just scraped back into office, as a minority government. Their eventual defeat five years later was not so surprising because by then they also were branded as a party of confusion and compromise and by the chaos of the so-called Winter of Discontent.

Familiar faces

But there was more to that defeat than the strikes and disruption of that winter. When Labour took over in March 1974 (a few days after the election were spent in Heath trying to survive in a coalition with the Liberals; as their leader then was Jeremy Thorpe it was probably just as well for them that the negotiations failed) they had a lot going for them. They were experienced and capable in the techniques of government; they knew how to run a ministry, deal with the higher-ranking civil servants, fight their battles in the Cabinet, persuade the working class that they were not doing what they actually were doing and so on. Such deceptions are always better received by the voters if they came from a familiar face and in people like Wilson. Callaghan, Healey and Jenkins Labour had some very familiar faces indeed. They had made themselves familiar during their previous spell in power, telling the working class that British capitalism was in crisis and they must tighten their belts to rescue it.

Barbara Castle, who was another familiar face mainly because as Minister of Transport she had brought in the breathalyser, excitedly confided to her diary: “We could turn out to be the most successful Labour government in history”. Harold Wilson promised everyone that the mistakes of the 1964-70 Labour government would not be repeated; for one thing he would confine himself to a relaxed vigilance to ensure that Labour carried out the promises in its election manifesto. On one past “mistake” he was specific. “A wage freeze is totally unacceptable. It would destroy this government”, he informed the Cabinet in December that year.

Barbara Castle, who was another familiar face mainly because as Minister of Transport she had brought in the breathalyser, excitedly confided to her diary: “We could turn out to be the most successful Labour government in history”. Harold Wilson promised everyone that the mistakes of the 1964-70 Labour government would not be repeated; for one thing he would confine himself to a relaxed vigilance to ensure that Labour carried out the promises in its election manifesto. On one past “mistake” he was specific. “A wage freeze is totally unacceptable. It would destroy this government”, he informed the Cabinet in December that year.

Within three days of the return the government had ended Heath’s state of emergency and Three Day Week, mainly by settling the coal strike. The Pay Board, set up by the Heath government to check on wage claims which were above the official limits, was abolished and in July statutory wage restraint was ended. Other titbits were thrown to a relieved and expectant electorate—a freeze on rents, a promise to increase pensions, control prices and subsidise food. Museum admission charges were abolished—who now remembers that they were ever free?

Social Contract

Labour’s alternative to the Heath governments statutory wage restraint was the Social Contract. This was the central plank of their wages policy which guaranteed an end to strikes and other industrial disruption. “It is”, Wilson assured us in their manifesto for the election in October 1974, “about economic justice between individuals and regions. It is about co-operation and conciliation, not conflict and confrontation”. In fact there was nothing new about the Social Contract since it was wage restraint by another name, based on the hope that the unions would moderate their wage claims in return for something called the Social Wage which covered things like state benefits, subsidies and rent control.

In October 1974, hoping that the workers would agree with their own assessment of their brief time in office (according to Wilson “no post-war British Government has achieved more in six months”) Labour called another election. Their hopes were not reflected in the re-election results; although there were 42 more Labour MP’s than Tories their overall majority was only three. To make matters worse the government was confronted with economic problems which made the Social Contract and the other promises in their manifesto look decidedly fragile—at a time when they could no longer blame the Tories for the mess they inherited.

Except that there was a different Chancellor of the Exchequer, it was like 1966 all over again. Early in 1975 Denis Healey was telling the unions, the Cabinet and anyone else who would listen that British capitalism’s big problem was “inflation”, and to beat it he proposed to cut public expenditure by £1 billion, including £62 million from the National Health Service. This was a bit puzzling to those Labour Party supporters who had believed their own propaganda that economic problems could easily be dealt with by increasing public expenditure. Some of them may also have wondered about Healey’s orthodox insistence that “inflation” was caused by excessive wage claims and his pressing for rises to be limited to ten percent which he knew, with prices rising as they were, would mean an effective cut in living standards of 2.5 percent. Was this, they may have asked themselves, what was meant by the Social Contract?

Soaking the rich

In any case the Social Contract did not survive for very long. In July 1975 the government more or less admitted that the whole idea was a lot of vote-catching nonsense when they announced a policy of virtually statutory wage restraint under which rises would be limited to £6 a week. The responsibility for such exposure of Labour’s electoral deceits was. of course, laid on greedy and irresponsible workers, who may have been taken in by Healey’s promise to squeeze the rich “until the pips squeak” and were unimpressed in a different way when he revised this, in February 1978, to “there is no way of avoiding (public expenditure cuts) by soaking the rich”. Labour’s desperate excuse for their assaults on workers’ living standards had always been that the alternative was even worse— mass unemployment. But this argument began to lose its terrors for the workers as, apart from what else was happening, unemployment began to rise—in January 1975 to 700,000 and a year later to well over a million.

Serious doubts about whether the government was losing their nerve were stimulated when, in July 1978, they produced a White Paper, Winning the Hattie Against Inflation, which announced their intention to hold pay rises to five percent and to impose sanctions against companies which settled above this level. In the circles where the pips were not yet squeaking—the CBI and the City—the White Paper’s promise of tighter controls on wages got a relieved welcome. In other circles, especially those where the lower paid no longer had any pips worth squeaking, it was regarded as the last straw. At the end of 1978 there was a flood of pay claims way above the White Papers limit. Local authority manual workers put in for 40 percent, road haulage and tanker drivers 25 percent to 30 percent and Ford settled a claim at 17 percent.

The media, where there was general agreement that workers were readier to live nearer the poverty line, illustrated their point with poignant pictures of streets obstructed with uncollected rubbish and stories of bodies lying unburied because of striking gravediggers. Among such workers. whose interests the Labour Party had promised to protect with special tenderness, the bitter realisation came that they had been conned.

By-elections

The Labour government’s excuse for all this was that they were fighting a battle which, provided we all obeyed orders, would result in a final solution to the economic problems of British capitalism and so unprecedented prosperity for us all. The extent to which this was believed can by gauged by the succession of by-election defeats in safe seats such as Walsall North, Stechford, Roy Jenkins’s old constituency (he had shrewdly removed himself to a remunerative and insulated job in Europe), and. greatest blow of all, the mining seat at Ashfield. Labour’s response to this was not to stand by their principles, go down fighting or any of the things mentioned in The Red Flag. Instead they compromised all they claimed to stand for, including that precious manifesto, by entering into a pact with the Liberals. This enabled them to carry on for a while; they were not embarrassed at the price they had to pay for their wretched survival.

By the end of their time in office the Labour Party had proved as conclusively as possible that capitalism was out of their control. Many of the promises they had made in opposition could not be fulfilled; many others, such as the Social Contract, had been tried only to be abandoned as failures. They had failed to do the one thing—eliminate unemployment, which Healey had described when in opposition in 1972 as “by far the biggest single cause of avoidable human misery and suffering”. When they lost power in 1979 there were 1.5 million people out of work. In 1974 they had promised that they could easily deal with such problems. Confronted with their failure to do so they resorted to hysterical attacks on the working class, such as their encouragement to cross picket lines and report over-forceful pickets to the police.

Labour’s time in power had prepared the workers into an acceptance of the Thatcher policies of so-called monetarism, cuts in public expenditure, screwing down state benefit claimants, restricting trade union power, and so on. The Tories exploited this situation to the full. Just as Labour had had victory handed to them on a plate in 1974 so the Conservatives had it five years later. There is a lesson in this, about the impotence of capitalism’s political parties in face of the system’s problems and their cynical response to it. Labour’s hope now is that we shall forget those lamentable years when they were the government and trust them to have a new approach, fresh ideas and a reborn determination not to make the same mistakes again. Well, whoever and whatever may be on their side in this, history is not.

Ivan